Month of Horrors 2012

“I am forced into speech because men of science have refused to follow my advice without knowing why.”

–H.P. Lovecraft

There is something primal about fear. Primal in the sense of evoking a kind of bodily lurch in what is animal in ourselves, as primal as lust and wonder, and in that sense almost amoral. While the Science Fiction genre is tied to the mundane world as it is or as we think it likely to become, and Fantasy is tied to the world as we would like to imagine it to be, Horror is the only one of the three that goes for the gut. In fact, it is one of a few genres that have as their main purpose to inflame a certain emotion. Romance incites lust, Comic fiction incites hilarity, and Horror incites fear. That someone would intentionally seek out literature that incites lust or hilarity is not difficult to understand, but why fear? What do people get out of empathizing with the helpless teenager who is being stalked by a serial killer, or with the man contemplating the starry sky after learning that what he thought to be endless beauty was in fact an endlessly dark terror?

It is this element of empathy with the frightened protagonist that I think distinguishes the modern Horror tale from pre-modern tales of ghosts, monsters, and the undead. Earlier stories like that of the Three Living and Three Dead were morality tales meant to engender a holy fear unto repentance—a far cry from The Walking Dead. Fairy tales were sometimes written to scare little children, but not adults. Pagan myths about monsters read almost more like curiosities than exercises in fright. Science Fiction and Fantasy are both more intellectual: one playing with the rules of the world as it is, the other wondering what it would be like if the rules were otherwise. Horror is all about emotion, and if the reader never feels scared while reading something of this genre, it is perceived to be a failure of the form.

It is this element of empathy with the frightened protagonist that I think distinguishes the modern Horror tale from pre-modern tales of ghosts, monsters, and the undead. Earlier stories like that of the Three Living and Three Dead were morality tales meant to engender a holy fear unto repentance—a far cry from The Walking Dead. Fairy tales were sometimes written to scare little children, but not adults. Pagan myths about monsters read almost more like curiosities than exercises in fright. Science Fiction and Fantasy are both more intellectual: one playing with the rules of the world as it is, the other wondering what it would be like if the rules were otherwise. Horror is all about emotion, and if the reader never feels scared while reading something of this genre, it is perceived to be a failure of the form.

So why do we bother with fictional fear? Isn’t the real world scary enough? Well, yes and no. There are many things to be frightened about in the world, perhaps even more so than in earlier, less technological ages, but the world we live in is oddly sanitized. Fears that high-level government and economic leaders are acting together against the common good are dismissed as nutty conspiracy theories. Fears that our loved ones will be hurt by what seem to be the increasingly evil people that populate our societies are contained in the therapist’s office. Fears about the afterlife are shrugged off by socially polite agnosticism. Fears about death are minimized by painkillers, euthanasia, sentimental funerals, and an avoidance of cemeteries. (Have you ever just visited a cemetery for the sake of the experience? People think you’re a goth nut on the hunt for poetic inspiration.) We repress our natural fears, but they cannot be denied forever. Horror novels and films are as socially acceptable a conduit as any for allowing oneself to truly feel fear.

The need for a Horror genre, or something like it, is very Freudian. It serves a psychological need that could perhaps be best sated by living a better kind of life, but which can be bandaged by slasher movies in a tight fix. The best Horror writers understand this need and exploit it without exploiting their readers (unlike Romance writers, who all exploit their readers). I expect we have our fair share of exploitive and “gross-out” Horror fiction on WWEnd, but unfortunately we’re still so ignorant about the genre around here that we honestly couldn’t tell which novel is which.

The need for a Horror genre, or something like it, is very Freudian. It serves a psychological need that could perhaps be best sated by living a better kind of life, but which can be bandaged by slasher movies in a tight fix. The best Horror writers understand this need and exploit it without exploiting their readers (unlike Romance writers, who all exploit their readers). I expect we have our fair share of exploitive and “gross-out” Horror fiction on WWEnd, but unfortunately we’re still so ignorant about the genre around here that we honestly couldn’t tell which novel is which.

The purpose of Month of Horrors is to explore this genre a little more, to feel out its architecture and boundaries. Scott Lazerus did us a great service back in April by exploring the roots of the Gothic sub-genre. Rico will be writing about the origins and influence of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein as October goes on. I will be reviewing whatever books I can get my hands on and finish before the month is out.

And of course we hope to feature your Horror novel reviews throughout the month, so get busy writing!

Month of Horrors is on Its Way…

…and WWEnd is looking for your book reviews to go with it!

Last year’s Month of Horrors was a huge success, but it was driven almost entirely by Rico and myself (with one great assist by Allie), but this year we’d like to feature reviews of Horror novels and collections from all of our members. All you need to do is start posting reviews to your favorite Horror novels, and we’ll pick the best ones for the blog.

Not sure where to start? Here’s a small sampling of the Horror books and authors currently on the site. And remember, if you can’t find a book in our database that you’d really like to review, drop us a line in the comments, and we’ll do what we can to add it.

Sub-Genres:

Authors:

- William Peter Blatty

- Ramsey Campbell

- Neil Gaiman

- Joe Hill

- Shirley Jackson

- Stephen King

- Dean Koontz

- H.P. Lovecraft

- Arthur Machen

- Peter Straub

Lists and Awards:

Month of Horrors: End of Month Wrap-Up

Today isn’t just Halloween, it’s also the closing day of WWEnd’s Month of Horrors, our 31-day celebration of the Horror genre in conjunction with adding this genre to the site. We’ve decided to wrap up the festivities with a dialogue between Rico and me about the genre. We may not be the biggest Horror aficionados in the world, but we both love literature, and I think we are both curious to see how it fits in the pantheon of genres, and especially how it relates to Science Fiction and Fantasy, the long-time staples of the WWEnd site.

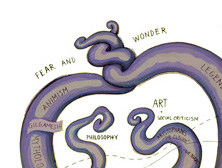

Jonathan: Ward Shelley in his infographic links genre fiction back into the primal emotions of Fear and Wonder. Arguably the Horror genre is far more about Fear than Wonder, though it often has its fair share of both. H. P. Lovecraft, of all people, occasionally wrote lyrically beautiful stories like “The White Ship” which were filled with wonder. But despite its primal roots, I don’t know of any previous body of literature that has focused so intently on the emotion of fear. In some ways, it reminds me of amusement park rides, which are built almost entirely to give the riders a thrill or a scare, the false feeling that their lives are in imminent physical danger even though everything is perfectly under control. I’ve often wondered if the thrill of fear is the primary draw for horror readers, if they are wanting to feel a “safe danger” like that of the amusement park ride. In other cases I suspect that the genre is a way of dramatically expounding on a philosophical or theological belief about the nature of the universe, the human condition, and the relationship between humanity and whatever cosmic powers might be. Do you have any thoughts on the genre from this perspective? Certainly I doubt that we will be able to fully unravel the mystery of any genre’s attraction—even Science Fiction is often more confounding than captivating to me—but I admire it if only as an outsider.

Jonathan: Ward Shelley in his infographic links genre fiction back into the primal emotions of Fear and Wonder. Arguably the Horror genre is far more about Fear than Wonder, though it often has its fair share of both. H. P. Lovecraft, of all people, occasionally wrote lyrically beautiful stories like “The White Ship” which were filled with wonder. But despite its primal roots, I don’t know of any previous body of literature that has focused so intently on the emotion of fear. In some ways, it reminds me of amusement park rides, which are built almost entirely to give the riders a thrill or a scare, the false feeling that their lives are in imminent physical danger even though everything is perfectly under control. I’ve often wondered if the thrill of fear is the primary draw for horror readers, if they are wanting to feel a “safe danger” like that of the amusement park ride. In other cases I suspect that the genre is a way of dramatically expounding on a philosophical or theological belief about the nature of the universe, the human condition, and the relationship between humanity and whatever cosmic powers might be. Do you have any thoughts on the genre from this perspective? Certainly I doubt that we will be able to fully unravel the mystery of any genre’s attraction—even Science Fiction is often more confounding than captivating to me—but I admire it if only as an outsider.

Rico: Horror does seem to have older roots than other genres. Whether it’s Odysseus trapped between the monster (Scylla) and a gaping nothingness (Charybdis), Hercules battling a hydra, or Jason facing the harpies, even the ancient Greeks felt the need for monstrous yarns. Lovecraft said this was because fear is our oldest emotion, especially fear of the unknown. In a lot of ways, it sort of drives us to find out what it is that scares us, so we can conquer it. Fear, then, is not so different from wonder.

Rico: Horror does seem to have older roots than other genres. Whether it’s Odysseus trapped between the monster (Scylla) and a gaping nothingness (Charybdis), Hercules battling a hydra, or Jason facing the harpies, even the ancient Greeks felt the need for monstrous yarns. Lovecraft said this was because fear is our oldest emotion, especially fear of the unknown. In a lot of ways, it sort of drives us to find out what it is that scares us, so we can conquer it. Fear, then, is not so different from wonder.

As to why horror is so attractive, however, we need a different explanation. Maybe one clue can be found in physiology. Sartre once observed that the symptoms of fear (dilation of the pupils, elevated heart rate, perspiration) also happen to occur when one falls in love. Two completely different conditions elicit the same bodily reactions. Because fear is so primal, it might be easier to frighten a reader than to make him/her fall in love. If the trill of a good scare gets me flushed in a way that is so love-like, why wouldn’t I enjoy it?

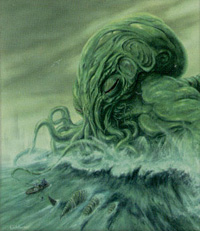

Jonathan: You mentioned both the Lovecraft and the ancient Greeks, but there’s a world of difference between the way each would approach a horrific tale. The Greeks had stories of monsters like Medusa and Typhon which, on the surface, are very similar to monsters like Lovecraft’s Cthulu, but while the Greek monsters might eat the occasional passerby and even level a mountain or two, Olympus could never truly lose the world to these monsters. Cthulu, on the other hand, will inevitably rise from the watery deeps to darken the sky and devour mankind. There’s the horror that is finite and destructible, like the Chimera and the Hydra, and then there’s the horror that devours not only people but hope. A classical tale of horror might end badly for some people, but it will also end with the sun still shining and regular people living their lives. A modern horror tale will often end with the emotional and psychological devastation of the protagonist, whose beliefs about the stability of the world have been crushed.

Jonathan: You mentioned both the Lovecraft and the ancient Greeks, but there’s a world of difference between the way each would approach a horrific tale. The Greeks had stories of monsters like Medusa and Typhon which, on the surface, are very similar to monsters like Lovecraft’s Cthulu, but while the Greek monsters might eat the occasional passerby and even level a mountain or two, Olympus could never truly lose the world to these monsters. Cthulu, on the other hand, will inevitably rise from the watery deeps to darken the sky and devour mankind. There’s the horror that is finite and destructible, like the Chimera and the Hydra, and then there’s the horror that devours not only people but hope. A classical tale of horror might end badly for some people, but it will also end with the sun still shining and regular people living their lives. A modern horror tale will often end with the emotional and psychological devastation of the protagonist, whose beliefs about the stability of the world have been crushed.

So while there is a kind of pleasurable (even love-like) thrill that can come from a frightening story, I don’t know that the Lovecraftian sort of total despair offers the same pleasure. David Hume once wrote about the stage tragedies of his day: “What [can be] so disagreeable as the dismal, gloomy, disastrous stories with which melancholy people entertain their companions?  The uneasy passion being there raised alone, unaccompanied with any spirit, genius, or eloquence, conveys a pure uneasiness, and is attended with nothing that can soften it into pleasure or satisfaction.” Do you think that modern horror perhaps offers the taste of that thrill without the pleasure, or am I being too harsh on it?

The uneasy passion being there raised alone, unaccompanied with any spirit, genius, or eloquence, conveys a pure uneasiness, and is attended with nothing that can soften it into pleasure or satisfaction.” Do you think that modern horror perhaps offers the taste of that thrill without the pleasure, or am I being too harsh on it?

Rico: I agree that there is a difference between the Greek stories and Lovecraft, but Lovecraft doesn’t define the genre. The world is still intact when the tell-tale heart stops beating, when the vampire finally gets staked, and when the last alien is flushed into space by Sigourney Weaver. Lovecraftian horror, it seems to me, is a special extremist sub genre. Of course, even it doesn’t find the world in tatters (there’d be no story if Hastur or Cthulu ever crossed over). It’s the threat of obliteration that makes the story exciting. In that sense, the Lovecraftian world really does share something in common with Odysseus and his men hovering on the brink of Charybdis, yet not quite falling in.

Also, although it’s true that the Olympic gods may not lose the world (well, there is one time, in the Iliad, when the Fates tell Zeus that he may defy them to save Troy, but that the cosmos would fall into chaos as a result), but humans certainly can lose their world. I’m thinking of Hecuba, for whom there can be no solace. Niobi (“all tears”) comes to mind. As in Lovecraft’s world, the gods take away everything.

Perhaps a better ancient analogue to Cthulu is Vishnu, the Hindu god whom Oppenheimer quoted as he reflected upon the nuclear horror he helped to create: “Now, I am become death, destroyer of worlds.”

Perhaps a better ancient analogue to Cthulu is Vishnu, the Hindu god whom Oppenheimer quoted as he reflected upon the nuclear horror he helped to create: “Now, I am become death, destroyer of worlds.”

Jonathan: Fair enough. In addition to the classical and modern horror narratives, it’s educational to look at the Medieval/Christian stories that most closely match the genre. Medieval poets loved singing about bizarrely chimeric beasts in addition to the demons and occult practitioners who frequently tormented the innocent. Meanwhile, Dante’s Inferno explored the greatest horror imaginable: everlasting damnation and torment. It’s a particularly interesting sort of horror, though, in that the one experiencing its pains has brought them upon himself. (Those in Dante’s version of Hell who are there by no vice of their own, like the unbaptized infants and the virtuous pagans, suffer no external pains.) When Dante tours the underworld, he is not witnessing the caprices of a cruel god, but the wasted lives of those who refused to do good and now suffer the consequences. The Medieval vision of Hell managed to combine the classical vision of celestial permanence and beauty with the all-consuming despair of a Lovecraftian apocalypse, as it’s inscribed on Hell’s doors: “Justice caused my high Architect to move… / The highest Wisdom, and the primal Love … / Abandon all hope you who enter here” (trans. Anthony Esolen).

To my mind, the best of the Horror genre is that which manages to keep both aspects of reality in play. When the balance tips entirely towards Tragedy (so to speak) or entirely in favor of Comedy, one feels that the poet or novelist isn’t being entirely honest about the way things are. Cormac McCarthy’s The Road is a magnificently-written novel, but it is arguably stuck in an emotional rut of bleak despair. As a counterpoint, Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings saga is a work which manages to drink the cup of futility to its last drop, without losing hope.

To my mind, the best of the Horror genre is that which manages to keep both aspects of reality in play. When the balance tips entirely towards Tragedy (so to speak) or entirely in favor of Comedy, one feels that the poet or novelist isn’t being entirely honest about the way things are. Cormac McCarthy’s The Road is a magnificently-written novel, but it is arguably stuck in an emotional rut of bleak despair. As a counterpoint, Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings saga is a work which manages to drink the cup of futility to its last drop, without losing hope.

Rich: That, it seems, is very much in keeping with Hallowe’en, which is a sort of twilight between the despair of loss (death) and the joy of All Saints Day (and All Souls Day, on November 2). The fact that today is an ’eve (and not the day itself) suggests a sort of lack of completion. We go out begging (trick or treating), perhaps because we lack something we want. All Hallows Evening is a darker anticipation of something miraculous, the feast day of every saint that ever was. There is, nay, there must be some sort of hope at the end of despair.

Jonathan: I’ll close simply by noting a small handful of Horror books I still plan to read, since I still feel inadequately-read in the genre. The Monk, The Castle of Otranto, and Melmoth the Wanderer are all at the top of my list as Gothic subgenre works; despite my recent bad experience with Nathaniel Hawthorne’s attempt at Gothic fiction, I still want to give it a try. I might also crack open some children’s horror with Neil Gaiman’s Coraline and The Graveyard Book. Joe Hill’s Horns is on the list, but a little further down.

What say you, Rico?

Rico: I’m likely to be more behind in my reading than you. It seems that much of the horror tradition is American, and may have roots not just in the English Gothic Novel, but also in the constant low-grade terror of North America’s indigenous population. Jung believed that tales of demonic possession waned in the American mind as rationalism took hold, and was replaced by stories of Indian abductions (and that those stories, in the 20th century turned into alien abductions!). This gets back to your idea of the unknown, and it makes me want to read all three kinds of "abduction" stories. The stories of Captain John Smith may sound more like a good old adventure story than horror, but it was a source of much anxiety to its readers in early America, who were more than familiar with the gruesome legacy of Roanoke. I also have an interest in the more recent accounts of body snatching: One such story is The Exorcist, which William Peter Blatty did not intend to be a horror novel at all. Another is I Am Legend, by Richard Matheson, which has inspired how many movies? If Jung were writing today, he might say that zombies are the latest incarnation of the abduction myth, and boy is it having its heyday, today.

Rico: I’m likely to be more behind in my reading than you. It seems that much of the horror tradition is American, and may have roots not just in the English Gothic Novel, but also in the constant low-grade terror of North America’s indigenous population. Jung believed that tales of demonic possession waned in the American mind as rationalism took hold, and was replaced by stories of Indian abductions (and that those stories, in the 20th century turned into alien abductions!). This gets back to your idea of the unknown, and it makes me want to read all three kinds of "abduction" stories. The stories of Captain John Smith may sound more like a good old adventure story than horror, but it was a source of much anxiety to its readers in early America, who were more than familiar with the gruesome legacy of Roanoke. I also have an interest in the more recent accounts of body snatching: One such story is The Exorcist, which William Peter Blatty did not intend to be a horror novel at all. Another is I Am Legend, by Richard Matheson, which has inspired how many movies? If Jung were writing today, he might say that zombies are the latest incarnation of the abduction myth, and boy is it having its heyday, today.

So that wraps up our Worlds Without End Month of Horrors! We hope you’ve all enjoyed our exploration of the Horror genre during the month of October. Cheery chills, and safe trick-or-treating!

Month of Horrors: Phantom

Guest Blogger, Allie McCarn, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on her blog Tethyan Books which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. She has already contributed many great book reviews to WWEnd and has generously volunteered to write some periodic reviews for our blog. Be sure to check out her site and let her know you found her here.

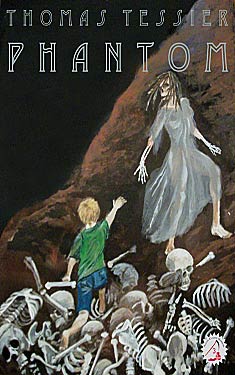

Phantom by Thomas Tessier

Phantom by Thomas Tessier

Published: Atheneum, 1982

The Book:

“Ned has known about phantoms since he was very young. You have to hide from them, under your bed covers. You can’t peek, because then you’ll see that they’re real. Then there’s no taking it back.

When Ned is almost ten, his parents move him from the city to a small town called Lynnhaven. Lynnhaven has its own ghosts—stories of people long gone and a ruined, abandoned spa that still remains. Ned seems to adapt well, befriending several local old-timers and spending his days fishing and playing. However, he slowly becomes aware that there is something dark waiting for him, and he associates it with the decrepit spa. He knows that sooner or later he will have to face his phantom…” ~Allie

Phantom, a novel on the Horror Writers Association Reading List, is my second review for WWEnd’s Month of Horrors. Phantom, which represents a very different style of horror than Conjure Wife, is a quieter, slower-paced story that focuses more on the kinds of fear that are probably familiar to everyone.

My Thoughts:

One of the strengths of Phantom as a horror story was the way it was built upon a foundation of realistic fear. First, it featured the (possibly) baseless terror children often experience while alone at night. I remember being an overly imaginative child, spending nights where every little sound or shifting shadow filled me with an irrational sense of doom. The actual events of Phantom moved well beyond usual childhood fright, but its basis in this kind of common fear made Ned’s situation much more relatable. The other, more serious, kinds of fear at the heart of the story were of the rational adult variety—fear of death or of losing someone you love. While childish fear certainly drove some of the creepier scenes, the mature fears were the ones that truly lent the story weight and made it memorable.

Despite the fact that the story involved both terror and phantoms, it was incredibly slow-paced. Most of the story involved Ned and his family getting settled in Lynnhaven. His mother and father both tried to help Ned adjust, in their own ways. For his part, Ned coped with the move by forging a friendship with two elderly men, Peeler and Cloudy. The relationship between Ned and the two men was absolutely adorable. Peeler and Cloudy took him along to fish or catch bait, and Ned eagerly listened to their old stories about former Lynnhaven residents. The development of Peeler and Cloudy’s peaceful friendship with Ned, or “Mr. Tadpole” as they called him, and Ned’s relationships with his parents filled a large part of the novel.

Despite the fact that the story involved both terror and phantoms, it was incredibly slow-paced. Most of the story involved Ned and his family getting settled in Lynnhaven. His mother and father both tried to help Ned adjust, in their own ways. For his part, Ned coped with the move by forging a friendship with two elderly men, Peeler and Cloudy. The relationship between Ned and the two men was absolutely adorable. Peeler and Cloudy took him along to fish or catch bait, and Ned eagerly listened to their old stories about former Lynnhaven residents. The development of Peeler and Cloudy’s peaceful friendship with Ned, or “Mr. Tadpole” as they called him, and Ned’s relationships with his parents filled a large part of the novel.

I enjoyed the focus on the characters and their relationships, but I was surprised at how much more emphasis was placed on everyday life than on frightening deviations from it. If you’re reading the story solely for thrills, I think it might become frustrating. The breaks between the more disturbing events are filled with pages of parental worries and conversations with Peeler and Cloudy. I don’t mean to say that exciting, creepy things don’t happen—Ned’s experiences with the spa are one example—but the thrills definitely take a back seat to character study and contemplative scenes of daily life.

The writing itself was concise and effective, but I was a little put off by the style of narration. The story is told from a third person omniscient point of view, and the thoughts and feelings of each person are generally described in every scene. The narration would hop from the mind of one person to the next between paragraphs, a style that I find personally jarring. It was never unclear whose thoughts were being related, but I felt that constantly moving from one person’s mind to another disturbed the flow of the story.

My Rating: 3.5/5

Phantom seems very much what I would expect from traditional horror, except for its slow, contemplative pace. It has a lot to say on the subject of fear, both the kinds of fears that plague small children and the inevitable fear of mortality with which I think most people eventually struggle. Rather than focusing on supernatural interference, the story focused more on the roots of a person’s fear and how it affects their lives. The thrilling, spine-tingling scenes were few and far between, but the bulk of the novel studied the relationships between Ned, his parents, and the elderly townsfolk Peeler and Cloudy. While it may not be packed full with action and suspense, the story of Ned and his phantom portrays many varieties of fear that will resonate with its readers.

Month of Horrors: The House of the Seven Gables

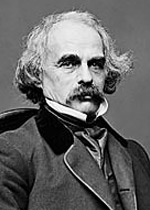

My introduction to the genre of Gothic Fiction was actually made not by a novel or short story, but by a graphic novel. Unlike the films, Mike Mignola’s Hellboy series is a dark and moody walk through crumbled castles and vine-ridden monasteries, albeit with the occasional gun fight and mad Nazi scientist. Reading it got me in the mood for more of the same, and after some research I discovered that Mignola was playing with a genre that’s been around for quite some time. The addition of the Guardian List brought with it a large selection of Gothic fiction to the WWEnd site, including one novel by an author I was already familiar with, Nathaniel Hawthorne.

By the time Hawthorne wrote his very popular House of the Seven Gables, he was working within an established genre whose shape and borders had already been established by such writers as Horace Walpole, William Beckford, Matthew Lewis, Charles Maturin, and Edgar Allan Poe. Hawthorne doesn’t disappoint any reader who comes to his novel expecting the same as what these earlier writers provided: ancient aristocratic homes, tyrannous judges, estranged relatives, unspeakable crimes from long ago, one-sided depictions of ancient religious communities, and of course a good haunting. While his book was and is well loved, I’m not sure that I agree with those who love it.

By the time Hawthorne wrote his very popular House of the Seven Gables, he was working within an established genre whose shape and borders had already been established by such writers as Horace Walpole, William Beckford, Matthew Lewis, Charles Maturin, and Edgar Allan Poe. Hawthorne doesn’t disappoint any reader who comes to his novel expecting the same as what these earlier writers provided: ancient aristocratic homes, tyrannous judges, estranged relatives, unspeakable crimes from long ago, one-sided depictions of ancient religious communities, and of course a good haunting. While his book was and is well loved, I’m not sure that I agree with those who love it.

But the fault isn’t, I think, with the genre itself. Even though this is probably the only novel I’ve read that accurately conforms to the classical tropes of the Gothic genre—authors like Bram Stoker and of H.P. Lovecraft wrote books similar to the Gothic, but were developing their own ideas—I still have a strong draw to its peculiar atmosphere. Hawthorne, though, is something of a hack writer, and that harms the novel.  Never content to allow a metaphor to remain implicit, he often spends multiple pages explicating an image he just inserted into the narrative, as though afraid its meaning might possibly pass a reader by. His prose is hardly bad in and of itself, but he can’t stop himself from pointing out his own cleverness. Adding to this weakness is his proclivity for digression, in which he interrupts an ongoing part of the narrative to talk about a character’s or object’s history, or to wax so poetic about something or other that the wax starts dripping all over the place. But for all his literary gurning, Hawthorne leaves a hugely important occurrence at the end of the narrative unexplained even after so much else is revealed. Sometimes one wishes he would shut up and tell the story.

Never content to allow a metaphor to remain implicit, he often spends multiple pages explicating an image he just inserted into the narrative, as though afraid its meaning might possibly pass a reader by. His prose is hardly bad in and of itself, but he can’t stop himself from pointing out his own cleverness. Adding to this weakness is his proclivity for digression, in which he interrupts an ongoing part of the narrative to talk about a character’s or object’s history, or to wax so poetic about something or other that the wax starts dripping all over the place. But for all his literary gurning, Hawthorne leaves a hugely important occurrence at the end of the narrative unexplained even after so much else is revealed. Sometimes one wishes he would shut up and tell the story.

Here’s part of Hawthorne’s description of the eponymous house:

All, as they approached, looked upward at the imposing edifice, which was henceforth to assume its rank among the habitations of mankind. There it rose, a little withdrawn from the line of the street, but in pride, not modesty. Its whole visible exterior was ornamented with quaint figures, conceived in the grotesqueness of a Gothic fancy, and drawn or stamped in the glittering plaster, composed of lime, pebbles, and bits of glass, with which the woodwork of the walls was overspread. On every side the seven gables pointed sharply towards the sky, and presented the aspect of a whole sisterhood of edifices, breathing through the spiracles of one great chimney. The many lattices, with their small, diamond-shaped panes, admitted the sunlight into hall and chamber, while, nevertheless, the second story, projecting far over the base, and itself retiring beneath the third, threw a shadowy and thoughtful gloom into the lower rooms. Carved globes of wood were affixed under the jutting stories. Little spiral rods of iron beautified each of the seven peaks.

Although The House of the Seven Gables is probably not the best example of Gothic fiction, its influence, especially on American horror, cannot be denied. Hawthorne himself is something of an acquired taste, but I know many people who think he’s one of the finest literary figures from early America. Maybe someday I’ll come around to their way of thinking, but it might be a while.

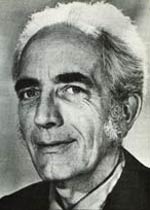

Month of Horrors: Conjure Wife

Guest Blogger, Allie McCarn, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on her blog Tethyan Books which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. She has already contributed many great book reviews to WWEnd and has generously volunteered to write some periodic reviews for our blog. Be sure to check out her site and let her know you found her here.

Conjure Wife by Fritz Leiber

Conjure Wife by Fritz Leiber

Published: Berkley Publishing Group, 1952

(originally in “Unknown Worlds”, 1943)

The Book:

“Life is going pretty well for Norman Saylor, Professor of Ethnology at the small College of Hempnell. His career is on the rise, and he knows that a large part of his success is due to the faithful, loving support of his wife, Tansy. One day, when he innocently pokes his nose into Tansy’s dressing room, he learns that she’s been using much more than her secretarial skills to make his life run more smoothly—she’s been using witchcraft.

Norman believes his studies of cultural superstitions have given rise to her ‘little witchcraft complex’, and he convinces her to stop it completely. However, after burning her protective charms, things begin to go wrong. Old and new enemies crop up, and his daily life begins to be plagued by many trivial—and some serious—difficulties. Is it all coincidence, or are there other magical forces at work, much more malevolent than Tansy’s protective charms? Will Norman continue to cling to his rational world, or will he be able to bring himself to trust in his wife before it is too late?” ~Allie

This is my first post for WWEnd’s Month of Horrors, which is welcoming the addition of the horror genre to the site! Conjure Wife is a selection from the Horror Writers Association Reading List, and it tells a story that is both creepy and full of suspense. This horror classic has been an inspiration for film multiple times over the decades (Weird Woman in 1944, Night of the Eagle/Burn, Witch, Burn! in 1962, and Witches Brew/Which Witch is Which? in 1988), and I think it well deserves its lasting fame.

My Thoughts:

Some elements of the society of Conjure Wife are firmly set in the 1940s, but the story itself is one that would work well in any era. In fact, with its juxtaposition of magic and mysticism with modern university life, it could be seen as a precursor to modern dark urban fantasy. The manipulation of tension in the story is masterful, and there were times when it was almost impossible to put the book down.

The magical and realistic elements of the story were woven together in a way that was suitably disturbing while rarely moving towards the absurd. Rather than going for Bewitched-style magic, the witchcraft of Conjure Wife seemed to be based more on actual practices, specifically the Hoodoo folk magic of the southern United States. Tansy’s main form of magic is the protective charms, which she calls ‘hands’, various objects ritually wrapped in flannel. The physicality of the magic and the references to (I assume) actual traditional practices lend weight and mystery to scenes featuring witchcraft.

While some of the dated elements of the story, such as the Norman’s references to psychoanalysis, were amusing, I was initially afraid that I would be turned off by the treatment of women and African Americans in the novel. Women’s rights, as well as the rights of African Americans, were not doing quite as well in the 1940s as they are today, and Conjure Wife is a product of its time. African Americans are only mentioned in reference to Hoodoo practices, which, I think, kind of plays into a popular fictional stereotype. The story also often discusses the fact that men are ‘naturally rational’, while women are ‘naturally intuitional’, and thus more likely to fall prey to superstition. However, when taken in the context of the society and the events of the story, these elements did not really come across as offensive. One interesting similarity to modern day is the contemporary attitudes toward universities. Norman notes that many people see large universities as “hotbeds of Communism and free love”. If you update the vocabulary (to left-wing politics and casual sex), then I imagine it would be quite easy to find a lot of people who would still make that claim.

While some of the dated elements of the story, such as the Norman’s references to psychoanalysis, were amusing, I was initially afraid that I would be turned off by the treatment of women and African Americans in the novel. Women’s rights, as well as the rights of African Americans, were not doing quite as well in the 1940s as they are today, and Conjure Wife is a product of its time. African Americans are only mentioned in reference to Hoodoo practices, which, I think, kind of plays into a popular fictional stereotype. The story also often discusses the fact that men are ‘naturally rational’, while women are ‘naturally intuitional’, and thus more likely to fall prey to superstition. However, when taken in the context of the society and the events of the story, these elements did not really come across as offensive. One interesting similarity to modern day is the contemporary attitudes toward universities. Norman notes that many people see large universities as “hotbeds of Communism and free love”. If you update the vocabulary (to left-wing politics and casual sex), then I imagine it would be quite easy to find a lot of people who would still make that claim.

Incidentally, Norman and Tansy Saylor want nothing more than to get back to one of those hotbeds. They are not nearly the respectable, staid couple that their career would seem to imply, though they are putting on a good show of it for the small, conservative college of Hempnell. They’re more accustomed to raucous drinking parties with their theatrical friends, but they’re currently resigned to playing bridge with the other faculty couples. Norman can’t quite give up some of his controversial ideas, such as his thoughts on premarital sex, despite how much it scandalizes the trustees.

For her part, Tansy is an intelligent and capable character, and a very powerful witch. She only practices protective magic, and she is remarkably selfless. Even when she’s in need of rescuing, she never completely loses her agency. The antagonists, on the other hand, are only very lightly developed as characters. Their motivations are clear and reasonable, but none of them have much depth. In general, I didn’t mind the weaker characterization of the antagonists, since I felt that the heart of this story was Norman, Tansy, and their relationship.

My Rating: 4.5/5

I was delighted with how well Conjure Wife still worked as a smoothly entertaining story, despite being written over half a century ago. Some aspects of social attitudes and setting were very clearly out of date, but others were still surprisingly relevant. I think the deciding factors in my enjoyment of the story were the characters of Norman and Tansy and the strength of the portrayal of their relationship. There’s clearly a reason that Conjure Wife has had such lasting fame, and I would fully recommend it to anyone looking for a suspenseful, magic-filled tale this Halloween season!

Month of Horrors: The Road

Cormac McCarthy’s novel The Road made some big waves when it was promoted through Oprah’s book club back in 2007. This led to an awkward interview on her talk show—McCarthy is notorious for avoiding any and all interviews—but it did wonders for his book sales. It’s fascinating that such a dark tale would be promoted in what can accurately be described as a pop venue, but I’m sure Cormac got some laughs knowing that his story of a man and his son desperately trying to survive in a post-apocalyptic wasteland would be read by housewives around the country.

Cormac McCarthy’s novel The Road made some big waves when it was promoted through Oprah’s book club back in 2007. This led to an awkward interview on her talk show—McCarthy is notorious for avoiding any and all interviews—but it did wonders for his book sales. It’s fascinating that such a dark tale would be promoted in what can accurately be described as a pop venue, but I’m sure Cormac got some laughs knowing that his story of a man and his son desperately trying to survive in a post-apocalyptic wasteland would be read by housewives around the country.

This drearily violent tale follows an unnamed man who is traveling to the ocean with his son (called only “the boy” by the author) across a land wasted by some unspecified disaster. At one point it’s suggested that this is a nuclear winter, but McCarthy leaves the cause of the earth’s death throes as unnamed as his protagonists. Realizing that they will not survive another winter at their current latitude, the father believes that moving south toward the ocean will bring some relief, and possibly better company than the roving gangs of thieves and cannibals they currently have to deal with at every turn.

McCarthy doubles down on the horror first by taking a hard, long look at the devastation that’s been brought down on the earth. There is little to no greenery left, nor any wildlife, and ash falls from the sky intermixed with snow. Just about the only food left is what can be scavenged from canned food stores, which leads to the second aspect of The Road’s horror, the cannibals. Those who are not strong enough to physically protect themselves are often taken alive to be eaten gradually, or else are used to, shall we say, generate more food.

McCarthy doubles down on the horror first by taking a hard, long look at the devastation that’s been brought down on the earth. There is little to no greenery left, nor any wildlife, and ash falls from the sky intermixed with snow. Just about the only food left is what can be scavenged from canned food stores, which leads to the second aspect of The Road’s horror, the cannibals. Those who are not strong enough to physically protect themselves are often taken alive to be eaten gradually, or else are used to, shall we say, generate more food.

The man and the boy wind their way through one horror after another in search of their goal, each horror more emotionally scarring than the last. At one point they are walking down a stretch of the road that had been melted by surrounding forest fires during the first days of the earth’s scorching. “The blacktop underneath had buckled in the heat and then set back again,” as McCarthy describes it. He goes on,

Boxes and bags. Everything melted and black. Old plastic suitcases curled shapeless in the heat. Here and there the imprint of things wrested out of the tar by scavengers. A mile on and they began to come upon the dead. Figures half mired in the blacktop, clutching themselves, mouths howling. He put his hand on the boy’s shoulder. Take my hand, he said. I dont think you should see this.

What you put in your head is there forever?

Yes.

It’s okay Papa.

It’s okay?

They’re already there.

I dont want you to look.

They’ll still be there.

He stopped and leaned on the cart. He looked down the road and he looked at the boy. So strangely untroubled.

Why dont we just go on, the boy said.

Yes. Okay.

They were trying to get away werent they Papa?

Yes. They were.

Why didnt they leave the road?

They couldnt. Everything was on fire.

They picked their way among the mummied figures. The black skin stretched upon their bones and their faces split and shrunken on their skulls. Like victims of some ghastly envacuuming. Passing them in silence down that silent corridor through the drifting ash where they struggled forever in the road’s cold coagulate.

I didn’t sleep well the night after finishing this novel.

(Image from stock.xchng, by Mario Alberto Magallanes Trejo.)

Month of Horrors: The Turn of the Screw

Science Fiction and Fantasy have done a little genre merging of late. Our tech has become a little more fantastic and our magic more technical. Steampunk has crossed over into the mainstream of fandom, kindling a new interest in the 19th century, in particular. Steampunk may be new, but it’s also old. In those heady days of the late 1800s, science fiction was in its infancy, and fantasy wasn’t selling. The hot genre was the ghost story — one of the founding fathers of modern horror.

Science Fiction and Fantasy have done a little genre merging of late. Our tech has become a little more fantastic and our magic more technical. Steampunk has crossed over into the mainstream of fandom, kindling a new interest in the 19th century, in particular. Steampunk may be new, but it’s also old. In those heady days of the late 1800s, science fiction was in its infancy, and fantasy wasn’t selling. The hot genre was the ghost story — one of the founding fathers of modern horror.

One of the great ghost stories is Henry James‘ classic, The Turn of the Screw. Published in 1898, just before the turn the of the century, James’ novel tapped into the freewheeling scientific inquiry of the time. The notion of "spiritual phenomena" was considered scientific and quite legitimate. Many intellectuals of the day professed a belief in ghosts, and séances were all the rage. Yet James approached his ghosts in a way that was as mysterious as the apparitions themselves. The ghosts in The Turn of the Screw are only ever witnessed by one character, and the veracity of her narration is sometimes in doubt. The brother of William James (a famous psychologist), Henry was the first to psychologize the notion of ghosts. The reader is free to suppose the shadowy figures as the delusion of an insane nanny, yet not comfortably. The ghosts themselves never seem to really interact with the world, but, instead, beckon their victims to harm themselves, again leaving room for interpretation. This is, perhaps, why the novella has survived as well as it has (certainly longer than the "science" of spiritualism) — because the ghosts live only in the corner of the reader’s eye. Examine a phenomenon like this too closely, and it vanishes.

The story is the first in a long line of psychological thrillers that have you doubting what you are seeing. Although it isn’t the first of the ghost story genre (Homer, Shakespeare, Dickens all came before), it is possibly the most copied in modern storytelling. After reading The Turn of the Screw, you’ll see subtle homages (intended or unintended) in films like Inception, where the unreliable nature of the human mind is writ large. Life on Mars also comes to mind: "Am I mad, in a coma, or back in time!" The novella even appeared several times in the series Lost, as a clue to eery happenings to come (even after the finale, many Losties were left wondering what was real).

The story is the first in a long line of psychological thrillers that have you doubting what you are seeing. Although it isn’t the first of the ghost story genre (Homer, Shakespeare, Dickens all came before), it is possibly the most copied in modern storytelling. After reading The Turn of the Screw, you’ll see subtle homages (intended or unintended) in films like Inception, where the unreliable nature of the human mind is writ large. Life on Mars also comes to mind: "Am I mad, in a coma, or back in time!" The novella even appeared several times in the series Lost, as a clue to eery happenings to come (even after the finale, many Losties were left wondering what was real).

Horror, at its best, tortures not just its characters, but its audience. If you decide to read this one, be prepared to have the screws turned on you.

Month of Horrors: The Metamorphosis

Franz Kafka’s novella The Metamorphosis exists in the same terrifyingly absurd sort of world as so many of his other stories. His characters are often oppressed by isolation and a sense of futility, and as such the horror they experience is part and parcel with the very act of living. In his novel The Trial, for instance, Josef K. is arrested and prosecuted for a crime unknown not only to the reader but to himself. Many of Kafka’s stories exist on the borders of madness and despair, something most Horror writers can only dream of accomplishing in their own work.

Franz Kafka’s novella The Metamorphosis exists in the same terrifyingly absurd sort of world as so many of his other stories. His characters are often oppressed by isolation and a sense of futility, and as such the horror they experience is part and parcel with the very act of living. In his novel The Trial, for instance, Josef K. is arrested and prosecuted for a crime unknown not only to the reader but to himself. Many of Kafka’s stories exist on the borders of madness and despair, something most Horror writers can only dream of accomplishing in their own work.

The Metamorphosis is a strangely-layered work pulling out of many literary traditions, but still seemingly unique. The title, for instance, is a reference to Ovid’s Metamorphoses, an ancient Roman work that retells Greek myths to make the philosophical point that all things are in a state of flux and transformation. The mutation of traveling salesman Gregor Samsa into a giant insect is reminiscent of werewolf stories… well, except for the insect part. The suddenness and unexplained nature of the mutation is a feature of absurdist and postmodern art, which has it that the world (contra Aristotle) is intrinsically irrational and chaotic. The unkindness of Gregor’s family as they fail to adjust to his curse is evocative even of the crueler sort of European fairy tales.

But despite all this, there is nothing that can quite prepare the reader for a story which describes the protagonist’s plight in this way: “His numerous legs, which were pitifully thin compared to the rest of his bulk, waved helplessly before his eyes.” It manages to be both disgusting and terrifying at the same time, something the Splatterpunk subgenre rarely achieves. Gregor’s attempts to move and talk in his new, inhuman body are pitiful, making one want to weep and vomit simultaneously. His family is uncertain whether this giant insect is still their son, though because of our privileged point of view, we know that he is. Only after his father has crippled him do they allow him to venture out of his room now and then. I won’t ruin the ending, but you wouldn’t be wrong to guess that it’s not a happy one.

But despite all this, there is nothing that can quite prepare the reader for a story which describes the protagonist’s plight in this way: “His numerous legs, which were pitifully thin compared to the rest of his bulk, waved helplessly before his eyes.” It manages to be both disgusting and terrifying at the same time, something the Splatterpunk subgenre rarely achieves. Gregor’s attempts to move and talk in his new, inhuman body are pitiful, making one want to weep and vomit simultaneously. His family is uncertain whether this giant insect is still their son, though because of our privileged point of view, we know that he is. Only after his father has crippled him do they allow him to venture out of his room now and then. I won’t ruin the ending, but you wouldn’t be wrong to guess that it’s not a happy one.

I’ll close with a brief passage, one which is fairly typical of Kafka’s writing. Good luck eating dinner afterwards!

Then he set himself to turning the key in the lock with his mouth. It seemed, unhappily, that he hadn’t really any teeth—what could he grip the key with?—but on the other hand his jaws were certainly very strong; with their help he did manage to set the key in motion, heedless of the fact that he was undoubtedly damaging them somewhere, since a brown fluid issued from his mouth, flowed over the key, and dripped on the floor.

(Translations by Willa and Edwin Muir)

Month of Horrors: In Praise of Unhappy Endings

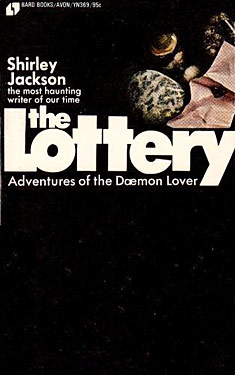

Since this is my first post for Month of Horrors, I thought I might make it a comment on the worthiness of horror as a genre. I must confess that I have not read many of the books in the HWA Reading List, but I have long been a fan of Shirley Jackson’s short story, The Lottery. Initial reaction to the story was negative, sparking hundreds of angry letters and negative comments. One letter even came from her own mother, who declared: “this gloomy kind of story is all you young people think about these days.”

To give too many details of Jackson’s classic story would be redundant. It is a very short story as it is. Suffice it to say, it’s about an annual stoning that takes places in a rural town in the 20th century. It’s classic horror, gloom and all. Like many examples of the genre, The Lottery takes ancient custom (in this case, human sacrifice) and juxtaposes it with a modern setting. The anachronism forces the reader to look at the brutality of our own past by making it more immediate. I selected the Lottery, not because it was the first (Poe and Lovecraft beat her to it by a century), but because it was (and is) the cleanest, simplest example of horror as a genre. It paints an everyday, almost welcoming picture of hometown USA, then cuts your throat and leaves you for dead. No wonder she had so much hate mail that summer!

To give too many details of Jackson’s classic story would be redundant. It is a very short story as it is. Suffice it to say, it’s about an annual stoning that takes places in a rural town in the 20th century. It’s classic horror, gloom and all. Like many examples of the genre, The Lottery takes ancient custom (in this case, human sacrifice) and juxtaposes it with a modern setting. The anachronism forces the reader to look at the brutality of our own past by making it more immediate. I selected the Lottery, not because it was the first (Poe and Lovecraft beat her to it by a century), but because it was (and is) the cleanest, simplest example of horror as a genre. It paints an everyday, almost welcoming picture of hometown USA, then cuts your throat and leaves you for dead. No wonder she had so much hate mail that summer!

Look, I’m a sucker for a feel-good story, just like the next guy, but literature is at its best when it doesn’t give us what we want. Readers may yearn for happy endings, but we need unhappy ones. They are a call to action. Often, they are a challenge to stifling tradition. In Jackson’s world, “Although the villagers had forgotten the ritual and lost the original black box, they still remembered to use stones.” Their tradition is dead in all but practice, yet stubbornly, it remains. John Steinbeck once said “a writer who does not passionately believe in the perfectibility of man has no dedication nor any membership in literature.” Horror shows us the imperfect in man, and forces us to look. Without those terrifying glimpses in the mirror, we would never improve; never take that bold decision for change. This failure to change is, of course, at the heart of Jackson’s story:

Look, I’m a sucker for a feel-good story, just like the next guy, but literature is at its best when it doesn’t give us what we want. Readers may yearn for happy endings, but we need unhappy ones. They are a call to action. Often, they are a challenge to stifling tradition. In Jackson’s world, “Although the villagers had forgotten the ritual and lost the original black box, they still remembered to use stones.” Their tradition is dead in all but practice, yet stubbornly, it remains. John Steinbeck once said “a writer who does not passionately believe in the perfectibility of man has no dedication nor any membership in literature.” Horror shows us the imperfect in man, and forces us to look. Without those terrifying glimpses in the mirror, we would never improve; never take that bold decision for change. This failure to change is, of course, at the heart of Jackson’s story:

"They do say," Mr. Adams said to Old Man Warner, who stood next to him, "that over in the north village they’re talking of giving up the lottery."

Old Man Warner snorted, "Pack of crazy fools," he said. "Listening to the young folks, nothing’s good enough for them. Next thing you know, they’ll be wanting to go back to living in caves, nobody work any more, live that way for a while. Used to be a saying about ‘Lottery in June, corn be heavy soon.’ First thing you know, we’d all be eating stewed chickweed and acorns. There’s always been a lottery," he added petulantly. "Bad enough to see young Joe Summers up there joking with everybody."

"Some places have already quit lotteries," Mrs. Adams said.

"Nothing but trouble in that," Old Man Warner said stoutly. "Pack of young fools."

What Mr. Adams points out in disgust actually gives the reader some tenuous thread of hope: that the young will rise up and challenge the town’s barely remembered tradition. At its best, horror makes us all young, and challenges us to tear down the unexamined impulses that make us all guilty. The Lottery meets this standard and then some, more than justifying Shirley Jackson’s place in the WWEnd canon.

Full Details

Full Details