Grand Master Reading Challenge April Review Winner: Allie

![]() The GMRC April Review Poll is closed and the winner is Allie! Her excellent review of the classic, To Your Scattered Bodies Go by Philip José Farmer, is her 4th GMRC review and her 69th(!) book review overall on WWEnd. Thanks, Allie, for your support! Check her profile page to see her other reviews and be sure to visit her blog for more great sci-fi and fantasy.

The GMRC April Review Poll is closed and the winner is Allie! Her excellent review of the classic, To Your Scattered Bodies Go by Philip José Farmer, is her 4th GMRC review and her 69th(!) book review overall on WWEnd. Thanks, Allie, for your support! Check her profile page to see her other reviews and be sure to visit her blog for more great sci-fi and fantasy.

For the win, Allie will receive a GMRC T-shirt, a GMRC button and a set of commemorative WWEnd Hugo Award bookmarks as well as her choice of books from the WWEnd bookshelf. Runners up will be getting a button and a set of bookmarks in the mail.

After 4 months we have 4 different winners. YOU could be next, so jump in with your own reviews – there are still more prizes to be won and there is plenty of time to get in your reviews for May.

I like to end these posts with a call to arms: "Tell your friends about the GMRC!" Well, apparently you’ve been doing just that! We’re up to 116 participants, 285 books read and 100 reviews. Huzzah! Well done, people. Well done. So, how high can we dive theose numbers from here? With only 12 books to read the GMRC is a challenge that you can easily catch up on if you miss the start but I suspect the law of diminishing returns will start kicking in all too soon. Might be a bit too steep to read 2 books a month so let everyone know it’s not too late to sign up… before it does become too late!

Book Drawing Winners!

The WWEnd Free Book Drawing is now closed. We had, in all, 72 entries, with many people entered thrice (on Twitter, Facebook, and WWEnd blog comments). After copying all names into a spreadsheet and assigning each one a number, we used a random number generator to select our first, second and third place winners. For the record, the numbers we generated were 1, 10, and 41. Congrats to our winners:

- J. W. Bjerk (jwbjerk) is our first place winner and has picked Thief’s Covenant by Ari Marmell.

- Sam Hankins came in second place but we’ve not been able to get in touch with him. Give us a shout Sam. You have a choice between Lightbringer by K. D. McEntire and Fair Coin by E. C. Myers.

- Jeremy Frantz (jfrantz) is our third place winner and will find out his prize once we hear back from Sam.

Besides the books our winners will receive a commemorative set of 2011 Hugo bookmarks.

This is the first of many book drawings, so stay tuned to this blog for future opportunities.

Update: Sam has chimed in with his pick for Lightbringer which leaves Fair Coin for Jeremy.

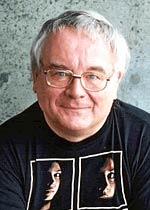

The Horror! The Horror! – Ramsey Campbell

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Charles Dee Mitchell, has contributed a great many book reviews to WWEnd including his extensive Philip K. Dickathon blog series. This is a new series where Dee explores the darker side of genre fiction and it’s practitioners. Be sure to visit his blog www.potatoweather.blogspot.com for more genre goodness.

Ramsey Campbell‘s home page opens with a quote from the Oxford Companion to English Literature. It informs us that Campbell is "Britain’s most respected living horror writer."

Ramsey Campbell‘s home page opens with a quote from the Oxford Companion to English Literature. It informs us that Campbell is "Britain’s most respected living horror writer."

My copy of the OCEL is a fifth edition and has no entry for Campbell at all. If it did, that first statement might be followed by this bit of information: Charles Dee Mitchell has attempted to read five of Mr. Campbell’s works and only succeeded in finishing three. And trust me, in the case of those I abandoned it was not because I was too terrified to turn another page.

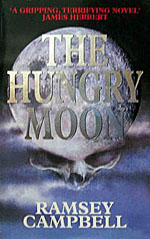

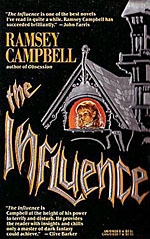

Ramsey Campbell may neither travel well nor date well. He has an American following but is a much bigger deal, obviously, in Great Britain. He is, after all, their most respected living horror writer. He has been publishing since the late 1950’s, and his most recent novel came out just this year from one of the presses that do high-priced, short runs of fantasy, horror, and science fiction titles. The books I tried were early to mid career novels. The Doll Who Ate His Mother (1976), The Face that Must Die (1979), The Nameless (1981), The Hungry Moon (1986), and The Influence (1988). Perhaps the past two decades have seen a remarkable transformation of his style and storytelling, but it is not as though the ones I read came un-recommended. The Face That Must Die was a somewhat fancy reprint with an introduction by Poppy Z. Brite and a few really bad illustrations. The Influence won the 1989 British Fantasy Award and is on the Guardian’s list of best sf and fantasy. The Hungry Moon, absolutely the worst of the lot, is the novel chosen by the Horror Writers Association to represent Campbell’s work.

Ramsey Campbell may neither travel well nor date well. He has an American following but is a much bigger deal, obviously, in Great Britain. He is, after all, their most respected living horror writer. He has been publishing since the late 1950’s, and his most recent novel came out just this year from one of the presses that do high-priced, short runs of fantasy, horror, and science fiction titles. The books I tried were early to mid career novels. The Doll Who Ate His Mother (1976), The Face that Must Die (1979), The Nameless (1981), The Hungry Moon (1986), and The Influence (1988). Perhaps the past two decades have seen a remarkable transformation of his style and storytelling, but it is not as though the ones I read came un-recommended. The Face That Must Die was a somewhat fancy reprint with an introduction by Poppy Z. Brite and a few really bad illustrations. The Influence won the 1989 British Fantasy Award and is on the Guardian’s list of best sf and fantasy. The Hungry Moon, absolutely the worst of the lot, is the novel chosen by the Horror Writers Association to represent Campbell’s work.

So is it just me? Of course, if that turned out to be the case, I would be the last person to admit it. I found the books mildly entertaining to unreadable. The thought that they might be genuinely frightening or even unnerving never crossed my mind.

So is it just me? Of course, if that turned out to be the case, I would be the last person to admit it. I found the books mildly entertaining to unreadable. The thought that they might be genuinely frightening or even unnerving never crossed my mind.

I’ll start with the ones I didn’t finish. The Hungry Moon is an overlong tale of Druid magic resurrected in the modern day by a religious nut. Campbell introduces us to too many of the residents of Moonwell, a village in Northern England. We learn what supposedly makes each one interesting and that takes a while. Then the event happens and we see how each of them react. Since I started skimming and finally quit the book, I don’t know the full panoply of horrible things that go on. But in the first chapter you learn that the village of Moonwell not only no longer exists but has been removed from maps, memories, and the telephone directory. The Influence concerns an evil great aunt out to possess the soul of her grandniece. If it had been a movie on TV and I could fast forward the commercials I would have watched it. But I couldn’t read it.

The other three novels are about psychopaths, two of them with some black magic references. The best of them is The Face that Must Die. The anti-hero, a Mr.Horridge, is a deranged young man obsessed with the evils of homosexuality. Great Britain decriminalized homosexuality in 1967, and decade later, Horridge sees the twisted results of the legislation everywhere he turns. He and his hammer will do what they can to remedy this situation. When the book first came out, portions were excised supposedly because they were too shocking. The complete text did not come out until 1982. Now the book just seems like fun. Horridge is crazy, and the block of flats on which he focuses his rage is peopled by characters only one of whom is gay and none of whom have any idea what’s coming. Like some of those old British stage thrillers, this is a shocker that now plays as black comedy.

The other three novels are about psychopaths, two of them with some black magic references. The best of them is The Face that Must Die. The anti-hero, a Mr.Horridge, is a deranged young man obsessed with the evils of homosexuality. Great Britain decriminalized homosexuality in 1967, and decade later, Horridge sees the twisted results of the legislation everywhere he turns. He and his hammer will do what they can to remedy this situation. When the book first came out, portions were excised supposedly because they were too shocking. The complete text did not come out until 1982. Now the book just seems like fun. Horridge is crazy, and the block of flats on which he focuses his rage is peopled by characters only one of whom is gay and none of whom have any idea what’s coming. Like some of those old British stage thrillers, this is a shocker that now plays as black comedy.

Campbell lives in Liverpool, and what he does best it create the down-in-the heel atmosphere and characters of that dismal, at least in his rendering, Northern England city. Everything is rundown, the weather is miserable, the people often not very bright. I especially liked the paranoid, pot-smoking hippie and the scatterbrained artist who lets a psychopath into her flat thinking he is the plumber.

So big deal, Mr. Campbell is not my cup of tea. If anyone, however, finishes The Influence, I am curious to know if anything even vaguely unpredictable happens by the time it is over.

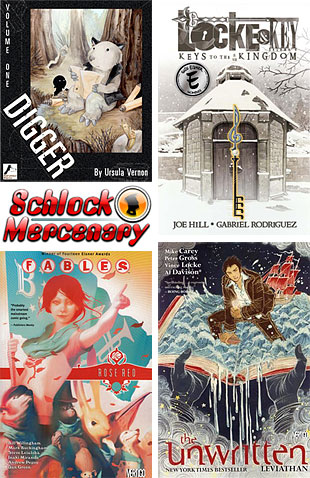

Graphic Stories, Unwrapped!

The fifth in our series of Hugo Voting articles (short story, novelette, novella, and related work preceding) is Best Graphic Story. Like Best Novel and Best Related Work, these books are rarely available online for free, but that is not without exception. Although the Hugo committee is likely to make novels, novellas, novelettes and short stories available for free for convention attendees and sponsors (a supporting membership is only $50), we do not believe graphic novels will be included in that reader packet. Consequently, you will need to find some online (two are free) and purchase/borrow/check out others, if you want to read them all.

The fifth in our series of Hugo Voting articles (short story, novelette, novella, and related work preceding) is Best Graphic Story. Like Best Novel and Best Related Work, these books are rarely available online for free, but that is not without exception. Although the Hugo committee is likely to make novels, novellas, novelettes and short stories available for free for convention attendees and sponsors (a supporting membership is only $50), we do not believe graphic novels will be included in that reader packet. Consequently, you will need to find some online (two are free) and purchase/borrow/check out others, if you want to read them all.

-

Digger, by Ursula Vernon is a webcomic, so may be read online for free. If you’d rather own the paper comic, each volume is about ten bucks, give or take, on Amazon.

-

Schlock Mercenary: Force Multiplication is also online for free and begins here. Although dead tree versions of Schlock Mercenary are available, Force Multiplication does not seem to be in print, yet.

-

Locke & Key Volume 4: Keys To The Kingdom, is in print, and the nominated volume 4 may be found at your local comic book shop or on Amazon or in electronic format on Comixology. If you’d like to start from the beginning, get volume 1.

-

Fables Vol 15: Rose Red also does not appear to be available online. Volume 15 is $12, or you could start the whole series in dead tree or Kindle formats. The ebooks are formatted only for the Kindle Fire or Kindle for Android, however.

-

The Unwritten (Volume 4): Leviathan is also available in print and Kindle editions, but volume 4 (the volume that was nominated) is only available in print, so far.

If any more of these volumes become available for free online, we will update this post.

Links to all of the award winning novels are, as always, available through BookTrackr.

Forays into Fantasy: Silverlock by John Myers Myers

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State College in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. Recently, he began branching out into fantasy, and was surprised by the diversity of the genre. It’s not all wizards, elves, and dragons! Scott’s new blog series, Forays into Fantasy, is an SF fan’s exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, building up an understanding of the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

John Myers Myers‘s Silverlock, published in 1949, is a recursive fantasy–a fantasy that makes use of settings or characters created by other authors, emphasizing the mutual influence and interrelatedness of all literature. Myers takes this conceit to its extreme, setting the novel on an island known as the Commonwealth–a reference to our shared inheritance of fictional and historical stories referred to by Joseph Addison as the "commonwealth of letters." In the Commonwealth, all stories coexist. The setting of Silverlock is all of literature and history!

John Myers Myers‘s Silverlock, published in 1949, is a recursive fantasy–a fantasy that makes use of settings or characters created by other authors, emphasizing the mutual influence and interrelatedness of all literature. Myers takes this conceit to its extreme, setting the novel on an island known as the Commonwealth–a reference to our shared inheritance of fictional and historical stories referred to by Joseph Addison as the "commonwealth of letters." In the Commonwealth, all stories coexist. The setting of Silverlock is all of literature and history!

In the first few chapters, Clarence Shandon, traveling on the Naglfar (the ship piloted by Loki during Ragnarok in Norse mythology), is shipwrecked. Assisted by Golias, who will become Shandon’s friend and guide, and who is also adrift in the ocean for reasons unknown, they witness the appearance of Moby Dick sinking the Pequod, after which they are able to make their way to the island of Aeaea, off the coast of the Commonwealth. Aeaea is the home of Circe (see Greek mythology for the details), who turns Shandon into a pig after he makes a pass at her. Golias helps him escape the island (and the influence of Circe’s spell), and they manage to swim to Robinson Crusoe’s island, where they are nearly captured by cannibals. Escaping in one of their kayaks, they nearly die of thirst before being picked up by a Viking ship, on their way to fight in the Battle of Clontarf (which took place when the Vikings invaded Ireland in 1014). Shandon is recruited as a rower, and he and Golias end up participating in the battle, barely escaping when the Vikings are routed. Separated from Golias, Shandon (now known as Silverlock, after the streak of premature gray in his hair) soon encounters Robin Hood and his men, helps Rosalette (a composite of Rosalind from As You Like It and Nicolette from the thirteenth-century French chantefable Aucassin and Nicolette) reunite with her lover, and joins the Mad Tea Party from Alice in Wonderland, among other adventures. After these travels, he manages to rendezvous with Golias, who is found in a tavern with Beowulf, celebrating the destruction of Grendel.

And all of this happens in the first third of the book. It’s the kind of novel that’s difficult to summarize without recounting too much detail, since it is so packed with incident and character, but I wanted to provide a taste of what the reading experience is like, and the way Myers combines story elements. A summary of the plot details, however, really misses the point. Instead, consider the main character. Shandon is a prototypical mid-twentieth century pragmatic American. When he is shipwrecked, he has little interest in saving himself, having become cynical and uninterested in life. "My only philosophy, if you could call it that, had been a contempt for life backed by a pride in that contempt." He is an educated man, but is clearly not the type to spend time with trivialities like art and literature. His arrival in the Commonwealth, however, plunges him into the world of stories, where he is ultimately transformed and enlightened by his exposure to the world of literature and history–in other words, the essence of human experience–and learns to reconnect with his humanity and regain a zest for living.

It’s not an easy path. At first he resists Golias’s attempts to involve him in his adventures. (I should note that Golias is a composite of various bard, minstrel, poet, and storyteller characters, and is referred to by many names throughout the novel.) He reluctantly agrees to assist a friend of Golias to claim his love and regain his inheritance, shamed into it by the presence of Beowulf, the ultimate hero. "Remembering what he had done to help out strangers, I simply could not let him hear me say that I would back out on a friend who was asking my help." The reform of his character has begun. The subsequent picaresque adventure occupies the second third of the novel, during which many other literary and historical figures are encountered. (Favorite incidents include an attempt to placate Don Quixote, and a trip on Huck Finn’s raft).

Mission accomplished, Golias unexpectedly tells Silverlock that they must separate. Shandon, who has finally gotten used to taking pleasure in the company of others, and thinks of Golias as his new best friend, doesn’t take it well, and his selfish reaction indicates that he still has some things to learn. Continuing to wander through the Commonwealth on his own, feeling bitter and cynical, his encounters become increasingly dark. He takes a ride on the Ship of Fools, runs into Job from the Old Testament (whose suffering makes it more difficult for Silverlock to feel sorry for himself), and is taken down into the Pit by "Faustophelese," where he encounters numerous examples of the dark side of human nature, along with other hellish denizens from various mythologies and Dante’s Inferno. His soul in danger, Silverlock is again rescued by Golias, now in the guise of Orpheus, and sent to drink from the spring of Hippocrene, the well of poetic inspiration in Greek myth. He doesn’t achieve the status of poet, but drinking from the spring allows him to remember his experiences in the Commonwealth, and receive passage back to his own world. He is taken aloft by Pegasus, and dropped into the ocean to be picked up by a passing ship.

Silverlock, then, is an allegory, but it’s much more fun than A Pilgrim’s Progress, as it includes much more drinking and singing. Shandon regains the joy of life, and Myers portrays that joy throughout. It’s a novel that shouldn’t work, yet does, and I put this down to the novel’s unique narrative perspective. The Commonwealth is not a fantasy setting in the usual sense. Those who read fantasy for the world-building aspect are likely to be disappointed, because this world makes no sense. Stories and characters from different historical periods coexist side by side, but the Vikings fight with bows, spears, and longships, oblivious to the fact that guns and steamboats are being used a few miles away. When Shandon encounters all of these characters and settings, he accepts them, never bringing up the fact that they are from stories. His pragmatic mind simply accepts the Commonwealth for what it is, and he never considers that his encounters seem designed to teach him lessons in living. This method allows the story to exist on several levels. The novel is narrated by Shandon, and from that direct perspective, Silverlock is a rollicking, rapidly-paced adventure story, full of excitement and interesting encounters, and can be enjoyed as such by readers mostly unaware of the literary allusions.

But for the reader with literary experience, those allusions provide another level of enjoyment. Since events are being described by someone entirely unfamiliar with the original stories, the reader must often identify the allusions without characters and settings being directly mentioned, but only described. For example, at one point Shandon and Golias find a raft and use it to travel toward their destination more quickly than they could on foot. The description of the river and their feelings while on the raft will identify it pretty quickly to anyone who has read Huckleberry Finn, but that story is never mentioned. Encountering Robin Hood or Don Quixote, Shandon doesn’t react by remembering the characters from a book or a movie, but his descriptions of their appearance and behavior will identify them to those familiar with the stories.

And I can guarantee that no reader will be familiar with all the stories. Nearly every detail in the book is taken from another story. Knowing that, I found myself continually trying to figure out the sources based on the descriptions in the novel, since they are not directly identified, and are often composites of similar characters from different stories (as in the case of Golias). This literary guessing game will be an enjoyable challenge for some readers, and is a big reason for the book’s cult following. Anyone trying to "get" all the references is bound to be disappointed, but the wonderful thing about Myers’s narrative method is that the novel can be enjoyed without getting them, so the reader can engage with that aspect of the novel to whatever degree she cares to.

And I can guarantee that no reader will be familiar with all the stories. Nearly every detail in the book is taken from another story. Knowing that, I found myself continually trying to figure out the sources based on the descriptions in the novel, since they are not directly identified, and are often composites of similar characters from different stories (as in the case of Golias). This literary guessing game will be an enjoyable challenge for some readers, and is a big reason for the book’s cult following. Anyone trying to "get" all the references is bound to be disappointed, but the wonderful thing about Myers’s narrative method is that the novel can be enjoyed without getting them, so the reader can engage with that aspect of the novel to whatever degree she cares to.

For anyone thinking of reading Silverlock, I strongly recommend getting the NESFA Press edition, which is still in print, since, along with being a beautiful book, it contains The Silverlock Companion, a hundred and fifty pages of supplementary material including, most importantly, "A Reader’s Guide to the Commonwealth," a concordance of the literary allusions. Coming across an unfamiliar character or place, it can be looked up in the guide and the original source identified. Along with discovering literary antecedents I was unaware of, or only vaguely aware of, this additional background added to my understanding of Myers’s reasons for choosing the stories for Silverlock to interact with, in relation to his own progress as a character. Browsing through this compendium of eighteenth and nineteenth century novels, Greek, Norse, Irish, Icelandic, and Chinese myths and legends, American tall tales, and Old English poetry, Myers’ amazing achievement is brought home. (And those examples just scratch the surface. There are hundreds of stories referenced in Silverlock.) His goal, however, is not to point out his own erudition, but rather to celebrate the role of stories in our lives. His story–Silverlock–is just one more small region to be annexed by the Commonwealth. Instead, he wants to remind us of the beauty–dramatic, comedic, tragic, romantic, fantastic–of the literary and historical heritage of humanity. Like Shandon, we can’t stay in the Commonwealth forever, but visiting it will enrich our lives by providing access to people, ideas, and experiences that enrich our understanding and enjoyment of life.

So, where does Silverlock fit in the history of fantastic literature? As mentioned above, it can be seen as a major exemplar of recursive fantasy, and many of its sources are the wellsprings of the fantastic–ancient myths, fairy tales, Arthurian legends, Beowulf, Dante’s Inferno…–thus being in a sense a fantasy about the fantastic. But since the narrator, Shandon, is unaware of the nature of the fantasy world he has entered, it does not come across as self-aware metafiction. As far as I know, then, Silverlock is unique in the history of fantasy. While there are plenty of other examples of recursive fantasy (Myers was probably influenced by L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt’s Incomplete Enchanter, for example), none that I know of operate in the way the Silverlock does. (If anyone knows of anything similar, I’d like to hear about it.)

Its uniqueness may explain its relative obscurity. As Myers wrote in 1980: "This was to be my big book, my contribution to the ages, and it flopped all over the place. Although it has since been revived by Ace in 1966, and again in 1979–it was an egg laid by an ostrich when it first came out and was remaindered." It’s been championed by its fans–Poul Anderson, Larry Niven, and Jerry Pournelle each wrote introductions to the 1979 edition–but it seems to be something of a cult item today, not well known to the community of fantasy readers, but extremely well-loved by those who do know it and appreciate it. According to David Pringle, who includes it in his Hundred Best, Myers "has produced a strange, harshly whimsical and rumbustious book… It will not be to every reader’s taste, but it is memorably different."

Its lack of success may have had to do with its timing. Prior to the 1920s, fantasy as a genre had yet to be ghettoized. Hawthorne, Melville, Henry James, Mark Twain, and Jack London all wrote fantasy without readers raising an eyebrow. It was just one of a number of fictional strategies used by these writers. By the time Silverlock was published, however, fantasy had mostly been relegated to the pulps. Silverlock, as a literary fantasy arriving in 1949, was ignored by the mainstream, simply because it was fantasy, while not being the sort of thing to interest the majority of the genre audience. In retrospect, we can ignore the genre prejudices and see it as part of a larger flowering of fantasy in the ‘40s and ‘50s that included, in America, de Camp and Pratt, Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser sequence; and, in the United Kingdom, Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast trilogy, C. S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia, and, of course, J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. Despite being the least well-known of these contemporaries, it deserves to be considered among them.

2012 John W. Campbell Memorial Award Finalists

The Center for the Study of Science Fiction has announced the John W. Campbell Memorial Award finalists for 2012.

- Ready Player One – Ernest Cline (Crown/Random House)

- This Shared Dream – Kathleen Ann Goonan (Tor Books)

- Soft Apocalypse – Will McIntosh (Night Shade Books)

- Embassytown – China Miéville (Ballantine Books/Del Rey)

- The Islanders – Christopher Priest (Gollancz)

- The Highest Frontier – Joan Slonczewski (Tor Books)

- Dancing with Bears – Michael Swanwick (Night Shade Books)

- Osama – Lavie Tidhar(PS Publishing)

- Robopocalypse – Daniel H. Wilson (Simon & Schuster)

- Home Fires – Gene Wolfe (Tor Books)

- Seed – Rob Ziegler (Night Shade Books)

The winner will be announced during the Campbell Conference, July 5-8, 2012.

Congratulations to all the nominees! What do you think of this list? Any surprises? With this nod, Embassytown, has garnered it’s 6th award nomination!

2012 British Fantasy Awards Shortlist

The British Fantasy Society has announced the shortlist for the 2012 British Fantasy Awards. This year there will be two awards in the best novel category: The August Derleth Award for best horror novel and The Robert Holdstock Award for best fantasy novel. The shortlist is:

- The Heroes – Joe Abercrombie (Gollancz)

- 11/22/63 – Stephen King (Hodder & Stoughton)

- Cyber Circus – Kim Lakin-Smith (NewCon Press)

- A Dance with Dragons – George RR Martin (Harper Voyager)

- The Ritual – Adam Nevill (Pan)

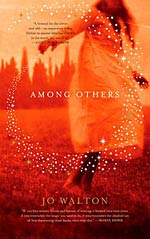

- Among Others – Jo Walton (Tor Books)

See the official press release for the complete shortlist of all categories. Congratulations to all the nominees!

So what do you think of this lineup? How about the split between fantasy and horror? I think it’s pretty cool but only 6 novels made the list for 2 categories? Will it always be an even split between fantasy and horror in the shortlist? I can see this getting messey.

Enter the WWEnd Free Book Drawing!

The good folks at Pyr recently sent us three fantastic looking books from their new Young Adult line. These are first run hardback editions from some exciting new authors and we’re putting them up for grabs. How can you get your mits on ’em? Simple, retweet, share or comment.

The good folks at Pyr recently sent us three fantastic looking books from their new Young Adult line. These are first run hardback editions from some exciting new authors and we’re putting them up for grabs. How can you get your mits on ’em? Simple, retweet, share or comment.

We’ve recently expanded our presence on Facebook and Twitter, and we’re eager to get the word out, so here’s how we’re going to do this. To enter the drawing, just retweet this tweet or share this Facebook post on your wall. We know not all of you are on social media, so you can also enter by commenting on this post. If you do all three, then you’ll triple your chances of winning.

We’ll randomly draw three names from all the entries. The first person will get their choice of the 3 books, the second will choose from the 2 remaining and the third will get the last available book. We’ll even throw in a set of our 2011 Hugo bookmarks. The drawing will be held on the 14th and is open to all – even our friends over the pond.

Be sure to include the name of the book you’d like to win in your entry.

Fair Coin

E. C. Myers

Ephraim is horrified when he comes home from school one day to find his mother unconscious at the kitchen table, clutching a bottle of pills. Even more disturbing than her suicide attempt is the reason for it: the dead boy she identified at the hospital that afternoon-a boy who looks exactly like him.

While examining his dead double’s belongings, Ephraim discovers a strange coin that makes his wishes come true each time he flips it. Before long, he’s wished his alcoholic mother into a model parent, and the girl he’s liked since second grade suddenly notices him. But Ephraim soon realizes that the coin comes with consequences-several wishes go disastrously wrong, his best friend Nathan becomes obsessed with the coin, and the world begins to change in unexpected ways.

As Ephraim learns the coin’s secrets and how to control its power, he must find a way to keep it from Nathan and return to the world he remembers.

Thief’s Covenant

Ari Marmell

Once she was Adrienne Satti. An orphan of Davillon, she had somehow escaped destitution and climbed to the ranks of the city’s aristocracy in a rags-to-riches story straight from an ancient fairy tale. Until one horrid night, when a conspiracy of forces-human and other-stole it all away in a flurry of blood and murder.

Today she is Widdershins, a thief making her way through Davillon’s underbelly with a sharp blade, a sharper wit, and the mystical aid of Olgun, a foreign god with no other worshippers but Widdershins herself. It’s not a great life, certainly nothing compared to the one she once had, but it’s hers.

But now, in the midst of Davillon’s political turmoil, an array of hands are once again rising up against her, prepared to tear down all that she’s built. The City Guard wants her in prison. Members of her own Guild want her dead. And something horrid, something dark, something ancient is reaching out for her, a past that refuses to let her go. Widdershins and Olgun are going to find answers, and justice, for what happened to her-but only if those who almost destroyed her in those years gone by don’t finish the job first.

Lightbringer

K. D. McEntire

Wendy has the ability to see souls that have not moved on-but she does not seek them out. They seek her. They yearn for her . . . or what she can do for them. Without Wendy’s powers, the Lost, the souls that have died unnaturally young, are doomed to wander in the never forever, and Wendy knows she is the only one who can set them free by sending them into the light. Each soul costs Wendy, delivering too many souls would be deadly, and yet she is driven to patrol, dropping everyone in her life but her best friend, Eddie-who wants to be more than friends-until she meets Piotr.

Piotr, the first Rider and guardian of the Lost, whose memory of his decades in the never, a world that the living never see, has faded away. With his old-fashioned charms, and haunted kindness, he understands Wendy in ways no one living ever could, yet Wendy is hiding that she can do more than exist in the never. Wendy is falling for a boy who she may have to send into the light.

But there are darker forces looking for the Lost. Trying to regain the youth and power that the Lost possess, the dark ones feed on the Lost and only Wendy and Piotr can save them-but at what cost?

The Drowned Cities by Paolo Bacigalupi

Scott Lazerus came to Worlds Without End looking for some good books to read. Luckily for us he decided to stay awhile and write some reviews. He recently launched a new blog series for us called Forays into Fantasy in which he explores the roots of the fantasy genre from a science fiction fan’s perspective.

In The Drowned Cities, Paolo Bacigalupi returns to the future America first envisioned in his 2010 young adult novel, Ship Breaker, enriching it by moving beyond his typical environmental concerns into a meditation on dysfunctional politics. Bacigalupi has said in interviews that, after a lot of work, he abandoned the attempt to write a direct sequel to Ship Breaker. Instead, The Drowned Cities introduces new characters to guide the reader further into the same world. Moving north from the setting of the previous novel, The Drowned Cities are what remains of Washington, D. C. and its environs, now engulfed by the rising ocean. Military forces led by competing warlords fight for control of the area, using conscripted child soldiers.

In The Drowned Cities, Paolo Bacigalupi returns to the future America first envisioned in his 2010 young adult novel, Ship Breaker, enriching it by moving beyond his typical environmental concerns into a meditation on dysfunctional politics. Bacigalupi has said in interviews that, after a lot of work, he abandoned the attempt to write a direct sequel to Ship Breaker. Instead, The Drowned Cities introduces new characters to guide the reader further into the same world. Moving north from the setting of the previous novel, The Drowned Cities are what remains of Washington, D. C. and its environs, now engulfed by the rising ocean. Military forces led by competing warlords fight for control of the area, using conscripted child soldiers.

Mahlia is a “castoff”–child of an African-American antiquities dealer and a Chinese peacekeeper. The peacekeepers attempted for over a decade to end the ongoing civil conflicts and promote economic development in the Drowned Cities, but eventually abandoned the effort. Mahlia’s father left with the rest of the peacekeepers, abandoning Mahlia and her mother, who is killed when the natives turn on everyone who had “collaborated” with the Chinese, including their castoff children. Mahlia loses a hand in the violence, but manages to escape due to the impulsive actions of a former farm boy named Mouse, who is also trying to survive in this violent world, having lost his parents to the fighting. Now inseparable, the two are adopted by Doctor Mahfouz, who is trying to help maintain a semblance of civilization in this fallen world, practicing medicine and stockpiling books from ruined libraries in the rural community of Banyan Town. Training her as a medical assistant, it is only his protection that keeps Mahlia relatively safe from the town’s hatred of castoffs. Their lives, already precarious, are disrupted by their discovery of the injured Tool–the one character carried over from Ship Breaker–who is on the run from soldiers of the United Patriot Front (UPF), who value him as an entertaining participant in their arena fighting tournaments. Tool is an “augment”–a genetically engineered fighting machine with human, hyena, dog, and tiger DNA. A fascinating character creation, it’s understandable that Bacigalupi wanted to explore him further.

When a band of UPF soldiers arrives, hunting for Tool, Banyan Town is caught in the middle, with serious consequences for the town, for Doctor Mahfouz, and for Mouse, who narrowly escapes death but is recruited by the UPF and forced to become a “soldier boy.” To what extent is Mahlia, who treated Tool’s injuries and refused to turn him over to the soldiers, responsible for these tragedies? Throughout the book, Bacigalupi plays with the ambiguity of responsibility in such extreme circumstances. In the midst of a war, to what extent can she be held responsible for the soldiers’ reactions in response to her refusal to give in to their demands? For that matter, to what extent are soldiers responsible for the violence they perpetrate under orders, especially when those soldiers are children who cannot survive outside of the “family” provided by their platoons? Ocho, a UPF soldier who, before the end of the novel, must make his own choice about perpetuating the cycle of war that has made him both a victim and a victimizer, defends the soldier boys, while recognizing the evil they are caught up in: “None of us asked for this! …None of us were like this…. We aren’t born like this. They make us this way.”

Unable to abandon the boy who at one time rescued her and attempting to make up for her role in these events, Mahlia makes what seems to be a suicidal decision to track Mouse into the Drowned Cities and rescue him from the UPF. Thus begins the adventure that makes up the second half of the novel, as well as Mahlia’s personal journey toward an understanding of the complexities of personal morality in a world where individuals are constrained by a dysfunctional society. Tool, who has his own scores to settle, accompanies her, their uneasy alliance growing as the novel progresses.

Like Ship Breaker, which won the Printz Award for best YA novel from the American Library Association and the 2011 Locus YA award, and was nominated for the National Book Award in the YA category, The Drowned Cities is being marketed as a young adult book, but it is a darker and more brutal story than its predecessor (which had its share of violence). Where Ship Breaker’s story arc was one of escape from a dead end life to a world of greater possibility (with much danger and hardship along the way), The Drowned Cities is a descent into the heart of darkness by its young protagonists. Hopefully, adults won’t be put off by the YA categorization. Though it lacks the narrative complexity of The Windup Girl, admirers of that novel are likely to find much to admire in this one.

Though the novel can be enjoyed strictly on the basis of Bacigalupi’s fluid prose and exciting story, a strong political subtext adds greatly to the interest for readers inclined to examine it. The future of America envisioned in the novel can be traced directly back to world we currently find ourselves in, and The Drowned Cities is firmly in the tradition of the dystopia as cautionary tale. But Bacigalupi avoids the traps of didacticism and preachiness by letting the setting and circumstances speak for themselves. Readers uninterested in this aspect of the book are still in for an exciting ride, but it is the ability to combine environmental, political and economic extrapolation with engaging storytelling and characterization that puts Bacigalupi’s work in the top rank of today’s science fiction. Readers of Bacigalupi’s other work will be familiar with the environmental aspects, but in The Drowned Cities he shows increasing concern with the political antecedents of his future America.

In this future, the country has been inundated by the effects of climate change. The southeast has devolved to a standard of living comparable to today’s undeveloped world as the result of coastal flooding, resource scarcity, and economic and political collapse. What’s left of the economy is based on scavenging resources for recycling, along with providing for only the most basic needs. The northeast is more functional, with “Seascape Boston” and “Manhattan Orleans” referred to as places the novels’ characters would like to escape to, although we haven’t yet seen what these areas are like. The northerners have created an army of augments to patrol the southern border in order to prevent the chaos, violence, and poverty of the south from spreading any further in their direction. These areas, as well as China, are home to powerful corporations that profit from recycling the salvage collected in the south, paying for safe passage through the war zones by trading weapons and ammunition to the local warlords.

Bacigalupi’s critique of America’s political direction goes beyond the inability to take steps to curb climate change. It is clear that the future plight he describes also relates to other aspects of current politics. China’s avoidance of devastation is telling, and can be extrapolated from the fact that China is currently being much more aggressive in pursuing alternative energy technologies to deal with a post-peak oil future than is the U.S., which is falling behind in investment in scientific education and research. China has responded to warming temperatures with massive investments in solar power technology, while in the U.S., politicians pray for rain. As a result, in the future of The Drowned Cities, China has the resources and political will to send peacekeeping forces to America, hoping to improve the situation there. Ironically, the Chinese effort to help is met with about as much enthusiasm among the native population as recent U.S. efforts in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Bacigalupi’s critique of America’s political direction goes beyond the inability to take steps to curb climate change. It is clear that the future plight he describes also relates to other aspects of current politics. China’s avoidance of devastation is telling, and can be extrapolated from the fact that China is currently being much more aggressive in pursuing alternative energy technologies to deal with a post-peak oil future than is the U.S., which is falling behind in investment in scientific education and research. China has responded to warming temperatures with massive investments in solar power technology, while in the U.S., politicians pray for rain. As a result, in the future of The Drowned Cities, China has the resources and political will to send peacekeeping forces to America, hoping to improve the situation there. Ironically, the Chinese effort to help is met with about as much enthusiasm among the native population as recent U.S. efforts in Iraq and Afghanistan.

What we learn about the history of the conflict in the Drowned Cities also comments on current U.S. political conditions. Along with the United Patriot Front, additional factions include the Army of God and the Freedom Militia, among others. While there is little difference in their tactics and goals–they all claim to want to kill the traitors (any factions other than themselves) and reunite the country–those titles all have echoes in today’s right-wing politics, where demonization of political opponents, intolerance of opposing views, and inability to compromise have become increasingly mainstream.

“The Drowned Cities hadn’t always been broken. People broke it. First they called people traitors and said they didn’t belong. Said these people were good and those people were evil, and it kept going, because people always responded, and pretty soon the place was a roaring hell because no one took responsibility for what they did, and how it would drive others to respond.”

Doctor Mahfouz explains to Mouse and Mahlia that the soldier boys are not “stupid and crazy,” as they assume, but are convinced by their ideals, and are fighting merely “to destroy their enemies.” “’But they call each other traitors,’ Mouse had said. ‘Indeed. It’s a long tradition here. I’m sure whoever first started questioning their political opponents’ patriotism thought they were being quite clever.’” The Drowned Cities attempts to show us what happens when too many people start believing the demagogic politicians and pundits.

I’ve had people tell me that they can’t read Bacigalupi because his stories are too depressing. Typically, they are not denying the importance of the issues his stories raise. Rather, they just don’t want to think about these things, preferring not to engage with this reality, at least not while they’re relaxing with a novel. Bacigalupi is aware of this reaction, and has said that it’s a common one among adults, who tend to feel powerless or cynical when confronted with the need to take action, and so often prefer not to be reminded of the need. He began writing for young adults because they are unlikely to have this reaction, having not yet given up on the potential to change things before they turn out the way his stories describe. In that sense, such stories can be inspirational rather than depressing.

In any case, The Drowned Cities (and Ship Breaker) are not depressing. In fact, the main characters in both novels take actions to improve their own situations, and the door is opened to the potential for the stricken communities to dig themselves out of the holes they have fallen into. Mahlia is an inspiring character in her ultimate refusal to accept the irrationality of her world.

“Done with being shoved around and threatened. Done with the bargaining that always said that if she wanted to live, someone else had to die. Done with armies like the UPF and Army of God and Freedom Militia, who all claimed that they’d do right, just as soon as they were done doing wrong.”

It may be depressing to consider the implications of the future Bacigalupi shows us, but it’s even more depressing to think that we could knowingly go down that road. The hope is that, just as young science fiction fans once grew up to work in the space program, wanting to achieve the space-going future they read about in the ‘40s and ‘50s, today’s young readers will be inspired to begin the work on the political and economic changes that could help us avoid the future seen in these novels. It’s certainly possible, if we can face the facts and work together. We may have to postpone space travel for a while (though I’m not willing to give up yet), but clipper ships powered by solar kite sails are pretty cool, too.

2012 Arthur C. Clarke Award Winner

The Testament of Jessie Lamb, by Jane Rogers (Sandstone Press), has won the 2012 Arthur C. Clarke Award.

The Testament of Jessie Lamb, by Jane Rogers (Sandstone Press), has won the 2012 Arthur C. Clarke Award.

The announcement was made today at the SCI-FI-LONDON Film Festival. For the win, Rogers received a check for £2012.00 and a commemorative engraved bookend trophy.

Congratulations to Jane Rogers on her win and to all the nominees:

- Hull Zero Three – Greg Bear (Gollancz)

- The End Specialist – Drew Magary (Harper Voyager)

- Embassytown – China Miéville (Macmillan)

- Rule 34 – Charles Stross (Orbit)

- The Waters Rising – Sheri S. Tepper (Gollancz)

Full Details

Full Details