Forays into Fantasy: Pulp Fantasy and A. Merritt’s The Ship of Ishtar

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State Colorado University in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. The Forays into Fantasy series is an exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today, from the perspective of an SF fan newly exploring the fantasy landscape. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, building up an understanding of the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

The 1920s saw a peak in interest in fantasy among “literary” writers. Modernist writers like James Joyce (Ulysses, 1922) and T. S. Eliot (The Waste Land, 1922), looking for universal themes among the technological, political, and social upheavals of the early twentieth century, increasingly incorporated mythology into their writing. Other literary writers of the decade took the further step of presenting mythological stories using all the tools of the modern novel. David Lindsay, Hope Mirrlees, Virginia Woolf, David Garnett, E. R. Eddison, Franz Kafka, Lord Dunsany, and James Branch Cabell all produced works that attempted to novelize the fantastic and the mythological.

The 1920s saw a peak in interest in fantasy among “literary” writers. Modernist writers like James Joyce (Ulysses, 1922) and T. S. Eliot (The Waste Land, 1922), looking for universal themes among the technological, political, and social upheavals of the early twentieth century, increasingly incorporated mythology into their writing. Other literary writers of the decade took the further step of presenting mythological stories using all the tools of the modern novel. David Lindsay, Hope Mirrlees, Virginia Woolf, David Garnett, E. R. Eddison, Franz Kafka, Lord Dunsany, and James Branch Cabell all produced works that attempted to novelize the fantastic and the mythological.

While this literary strain of fantasy never entirely died out, it waned in subsequent years, as the second main strain of fantasy—that appearing in the pulp magazines—increased its dominance. The appeal to escapism and sensationalism associated with pulp fantasy and science fiction (as well as some atrocious writing) may have helped make the genre increasingly unacceptable to the literati, but the literary accomplishments of the 1920s are an indicator of what might have been, if the potential audience for these works had not been turned against the literary potential of fantasy by the reputation of the pulps, especially once the specialized genre pulps Weird Tales and Amazing Stories appeared with much success in the late 1920s.

I’ve written previously about the role of Edgar Rice Burroughs as the best-known exemplar of pulp fantasy, but during the 1920s, A. Merritt, though not as well-remembered today, would rival Burroughs in popularity, and is still considered to be one of the most popular fantasy authors of all time. His works were held in such high regard among fans that, when the previously unknown Francis Stevens (Gertrude Barrows Bennett) came on the scene, the quality of her work led many to assume that Stevens was a pseudonym for Merritt. The popularity of reprints of Merritt’s stories in the pulp Famous Fantastic Mysteries convinced its publisher to launch A. Merritt’s Fantasy Magazine as a companion in 1949, six years after Merritt’s death and three decades before similar name recognition would motivate the launch of Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine. While Burroughs’s Africa and Mars were fantasy settings, they were based on real places. Merritt, on the other hand, like many of the writers mentioned above, used mythology and history as the basis for his stories, fusing these with pulp adventure and colorful but not always entirely grammatical prose.

I’ve written previously about the role of Edgar Rice Burroughs as the best-known exemplar of pulp fantasy, but during the 1920s, A. Merritt, though not as well-remembered today, would rival Burroughs in popularity, and is still considered to be one of the most popular fantasy authors of all time. His works were held in such high regard among fans that, when the previously unknown Francis Stevens (Gertrude Barrows Bennett) came on the scene, the quality of her work led many to assume that Stevens was a pseudonym for Merritt. The popularity of reprints of Merritt’s stories in the pulp Famous Fantastic Mysteries convinced its publisher to launch A. Merritt’s Fantasy Magazine as a companion in 1949, six years after Merritt’s death and three decades before similar name recognition would motivate the launch of Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine. While Burroughs’s Africa and Mars were fantasy settings, they were based on real places. Merritt, on the other hand, like many of the writers mentioned above, used mythology and history as the basis for his stories, fusing these with pulp adventure and colorful but not always entirely grammatical prose.

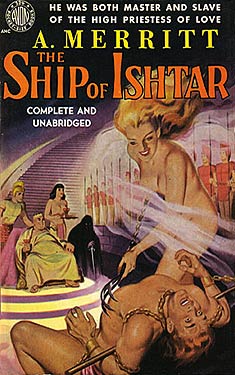

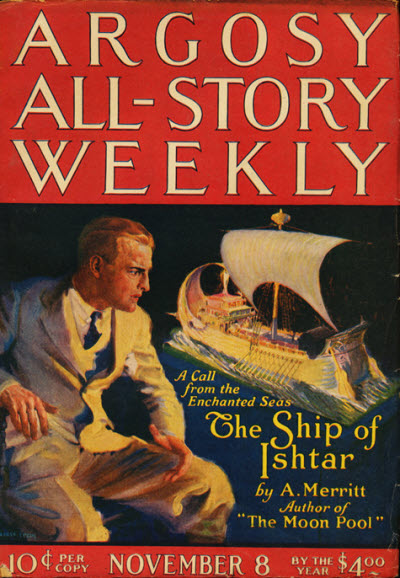

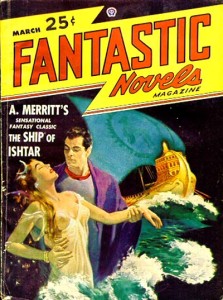

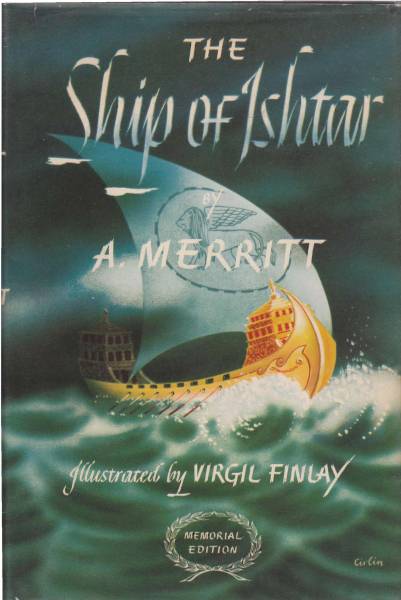

Abraham Merritt (1884–1943) published his first work in All-Story Weekly in 1917. (Burroughs’s first work had appeared in the same magazine five years earlier.) By 1923, with his third novel, The Ship of Ishtar (1924), Merritt had, according to James Cawthorn and Michael Moorcock, reached “the peak of his powers,” and would continue publishing well into the 1930s, his stories maintaining their popularity as reprints in the genre magazines of the 1940s and 1950s. For several decades, Merritt was considered by knowledgeable fans of pulp fantasy to be the top writer of the genre. Yet today, Merritt, unlike Burroughs, seems to be mostly forgotten by all but pulp aficionados. This may be because, even more so than Burroughs, Merritt’s prose comes across as, by turns, flowery and stilted, without the compensations of the sort of detailed inventiveness carried on over multiple series volumes that draws in the fans of Tarzan and John Carter. As long as readers of the pulp era made up a sizable portion of genre fans, Merritt’s reputation endured, but that reputation doesn’t seem to have survived into the era of epic fantasy, despite being a clear forerunner of that sub-genre. Unlike Merritt, Burroughs was still being avidly read by fans into the 1970s, but even his reputation is probably maintained today largely by nostalgia. While pulp fantasy may have eclipsed literary fantasy by the 1930s, it could not survive in an era of reader expectations set by Tolkien and his descendants.

Abraham Merritt (1884–1943) published his first work in All-Story Weekly in 1917. (Burroughs’s first work had appeared in the same magazine five years earlier.) By 1923, with his third novel, The Ship of Ishtar (1924), Merritt had, according to James Cawthorn and Michael Moorcock, reached “the peak of his powers,” and would continue publishing well into the 1930s, his stories maintaining their popularity as reprints in the genre magazines of the 1940s and 1950s. For several decades, Merritt was considered by knowledgeable fans of pulp fantasy to be the top writer of the genre. Yet today, Merritt, unlike Burroughs, seems to be mostly forgotten by all but pulp aficionados. This may be because, even more so than Burroughs, Merritt’s prose comes across as, by turns, flowery and stilted, without the compensations of the sort of detailed inventiveness carried on over multiple series volumes that draws in the fans of Tarzan and John Carter. As long as readers of the pulp era made up a sizable portion of genre fans, Merritt’s reputation endured, but that reputation doesn’t seem to have survived into the era of epic fantasy, despite being a clear forerunner of that sub-genre. Unlike Merritt, Burroughs was still being avidly read by fans into the 1970s, but even his reputation is probably maintained today largely by nostalgia. While pulp fantasy may have eclipsed literary fantasy by the 1930s, it could not survive in an era of reader expectations set by Tolkien and his descendants.

While some of the pulp fantasists are still worth going back to (Francis Stevens, C. L. Moore, Robert E. Howard and H. P. Lovecraft come to mind), continued interest in these writers is due mostly to the fact that they, in various ways, rose above the typical pulp formulas, allowing us to get past some of the purple prose and other literary defects. A. Merritt, on the other hand, has less to offer today’s readers. The same aspects of his writing that worked as virtues for fans in the first half of the twentieth century appear as vices in the twenty-first. The distracting prose style, the lack of characterization, the explicit appeal to prurience and escapism, and the sexist and racist elements common to genre writing from this period, combine into a rather unattractive package in The Ship of Ishtar. On the other hand, there is an appealing weirdness to the story and setting, a few rousing adventure set-pieces, and an interesting mash-up of ancient cultures and mythologies. A very strong imagination is at work, and this will overcome the defects for some readers. Overall, though, I suspect that Merritt remains of interest mostly to those with a strong taste for the pulps, or a historical interest in the development of the heroic fantasy genre.

While some of the pulp fantasists are still worth going back to (Francis Stevens, C. L. Moore, Robert E. Howard and H. P. Lovecraft come to mind), continued interest in these writers is due mostly to the fact that they, in various ways, rose above the typical pulp formulas, allowing us to get past some of the purple prose and other literary defects. A. Merritt, on the other hand, has less to offer today’s readers. The same aspects of his writing that worked as virtues for fans in the first half of the twentieth century appear as vices in the twenty-first. The distracting prose style, the lack of characterization, the explicit appeal to prurience and escapism, and the sexist and racist elements common to genre writing from this period, combine into a rather unattractive package in The Ship of Ishtar. On the other hand, there is an appealing weirdness to the story and setting, a few rousing adventure set-pieces, and an interesting mash-up of ancient cultures and mythologies. A very strong imagination is at work, and this will overcome the defects for some readers. Overall, though, I suspect that Merritt remains of interest mostly to those with a strong taste for the pulps, or a historical interest in the development of the heroic fantasy genre.

The Ship of Ishtar is the story of John Kenton, who exemplifies a common character type in pulp fantasy—a man, stifled or undervalued in the modern world, who finds happiness in a less technological, less civilized fantasy world, where his manly virtues can be fully appreciated. Dissatisfied with contemporary life, Kenton is a war veteran who has worked as an archaeologist, but has become disinterested even in that. The arrival of a strange block of stone from a dig he has financed presents him with a means of escape into the past, and a life of adventure. The block dissolves in his hands, revealing a model of an ancient ship, six thousand years old. Its deck is half ivory and half ebony, symbolic of a fight between good and evil in a parallel world frozen in place since the model was encased in stone. Now released, the model ship magically transports Kenton to the “real” Ship of Ishtar, where the followers of Ishtar, Assyrian goddess of love, and Nergal, god of war, maintain a hostile stalemate, seemingly sentenced to sail the ship eternally as a result of a forbidden love affair between the High Priestess of Ishtar and the High Priest of Nergal, who have succeeded in escaping the ship through the power of that love. Left behind, the remaining priests, priestesses, and servants of the gods, led by Sharane and Klaneth, continue the conflict.

The Ship of Ishtar is the story of John Kenton, who exemplifies a common character type in pulp fantasy—a man, stifled or undervalued in the modern world, who finds happiness in a less technological, less civilized fantasy world, where his manly virtues can be fully appreciated. Dissatisfied with contemporary life, Kenton is a war veteran who has worked as an archaeologist, but has become disinterested even in that. The arrival of a strange block of stone from a dig he has financed presents him with a means of escape into the past, and a life of adventure. The block dissolves in his hands, revealing a model of an ancient ship, six thousand years old. Its deck is half ivory and half ebony, symbolic of a fight between good and evil in a parallel world frozen in place since the model was encased in stone. Now released, the model ship magically transports Kenton to the “real” Ship of Ishtar, where the followers of Ishtar, Assyrian goddess of love, and Nergal, god of war, maintain a hostile stalemate, seemingly sentenced to sail the ship eternally as a result of a forbidden love affair between the High Priestess of Ishtar and the High Priest of Nergal, who have succeeded in escaping the ship through the power of that love. Left behind, the remaining priests, priestesses, and servants of the gods, led by Sharane and Klaneth, continue the conflict.

Arriving out of nowhere, Kenton is suspected of being a spy by both sides, but eventually wins the confidence (and love) of Sharane, pitting him against Klaneth and the other followers of Nergal. With the help of his modern knowledge and intelligence (and consistent with another common trope of pulp fantasy), Kenton shows himself superior to all on the Ship, managing to take it under his command, driving off Klaneth while “taking” the beautiful and proud Sharane. The scene in which Sharane succumbs to Kenton, having previously snubbed him, is characteristic of Merritt’s style, and both that style and the content of this section indicate why Merritt may seem unpalatable to modern readers:

Arriving out of nowhere, Kenton is suspected of being a spy by both sides, but eventually wins the confidence (and love) of Sharane, pitting him against Klaneth and the other followers of Nergal. With the help of his modern knowledge and intelligence (and consistent with another common trope of pulp fantasy), Kenton shows himself superior to all on the Ship, managing to take it under his command, driving off Klaneth while “taking” the beautiful and proud Sharane. The scene in which Sharane succumbs to Kenton, having previously snubbed him, is characteristic of Merritt’s style, and both that style and the content of this section indicate why Merritt may seem unpalatable to modern readers:

“My lord—I pray you forgiveness,” she sighed. “I pray you forgiveness! Yet how could I have known—when first you lay upon the deck and seemed afraid and fled? I loved you! Yet how could I have known how mighty a lord you are?”

Her fragrance shook him; the softness of her against his breast closed his throat.

“Sharane! He murmured. “Sharane!”

His lips sought hers and clung; mad wine of life raced through his veins; in the sweet fire of her mouth memory of all save this moment burned away.

“I—give myself—to you!” she sighed.

He remembered…

“You give nothing, Sharane,” he answered her. “I—take!” He lifted her in his arms; he strode through the rosy cabin’s door; shut it with thrust of foot and hurled down its bar.

His prowess and personality also win the loyalty of a motley selection of followers from various eras of history, all of whom have been, like Kenton, drawn to this strange world—the apish Gigi, the Persian Zubran, and the Viking Sigurd. Together, they must fight their way across the ocean and through the colorful cities and temples of this strange world, the forces of evil always on their trail. Klaneth’s attacks must be fought off and a kidnapped Sharane rescued. Their quest seems doomed, considering the forces arrayed against them, but this is supposed to make Kenton and his followers appear all the more heroic.

His prowess and personality also win the loyalty of a motley selection of followers from various eras of history, all of whom have been, like Kenton, drawn to this strange world—the apish Gigi, the Persian Zubran, and the Viking Sigurd. Together, they must fight their way across the ocean and through the colorful cities and temples of this strange world, the forces of evil always on their trail. Klaneth’s attacks must be fought off and a kidnapped Sharane rescued. Their quest seems doomed, considering the forces arrayed against them, but this is supposed to make Kenton and his followers appear all the more heroic.

At the times of greatest danger or conflict, Kenton is inexplicably and unwillingly drawn back to his New York City apartment, and must “will” his way back to his “great adventure.” Time passes much more quickly in the world of the Ship, and a few minutes in New York result in Kenton returning to the scene of battle weeks later. And Kenton always wants desperately to go back, despite all indications that he is bound to die there, and the suffering and injury that he repeatedly endures. As the story progressed, Kenton became ever less sympathetic in my eyes. His dissatisfaction with his life in New York (for which no particular reason is given) is contrasted with his overwhelming desire to return to a fantasy world where he can satisfy his lusts for sex, violence, and the comradeship of battle. Sensationalism was part of the pulps’ lure, and Merritt must have satisfied his readers on this score. While it’s unlikely to seem remarkable to modern readers, I was a little surprised at the clear appeal to the prurient interests of male readers, with a level of gore and sexual motivation more explicitly presented than in other pulp fantasy I’ve read

Despite the elements of The Ship of Ishtar that were well done, mostly involving the imaginative use of mythology and the fantastic, it was the sensationalist escapism that ultimately turned me against the book. I got the impression that Kenton was supposed to symbolize the way modern man, his primal nature stifled by the requirements of civilization, will only find fulfillment through the satisfaction of his instincts for lust and conflict. Women are to be taken, joy is found in war, the whipping of the slaves who man the oars of the Ship of Ishtar is unquestioned. Despite the high adventure, this theme ultimately makes The Ship of Ishtar something of a descent into darkness. Merritt may have realized this. While seeming to celebrate the appeal of the basest sort of masculine fantasy throughout the novel, he also accepts that the pure embrace of primal motivations does not lead to a happy ending. For men like Kenton in the real world, there is no escape, though the pages of the pulps may have offered temporary solace to those looking for a less complicated world.

Despite the elements of The Ship of Ishtar that were well done, mostly involving the imaginative use of mythology and the fantastic, it was the sensationalist escapism that ultimately turned me against the book. I got the impression that Kenton was supposed to symbolize the way modern man, his primal nature stifled by the requirements of civilization, will only find fulfillment through the satisfaction of his instincts for lust and conflict. Women are to be taken, joy is found in war, the whipping of the slaves who man the oars of the Ship of Ishtar is unquestioned. Despite the high adventure, this theme ultimately makes The Ship of Ishtar something of a descent into darkness. Merritt may have realized this. While seeming to celebrate the appeal of the basest sort of masculine fantasy throughout the novel, he also accepts that the pure embrace of primal motivations does not lead to a happy ending. For men like Kenton in the real world, there is no escape, though the pages of the pulps may have offered temporary solace to those looking for a less complicated world.

Full Details

Full Details

No comments yet.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.