Graphic Stories, Unwrapped!

The fifth in our series of Hugo Voting articles (short story, novelette, novella, and related work preceding) is Best Graphic Story. Like Best Novel and Best Related Work, these books are rarely available online for free, but that is not without exception. Although the Hugo committee is likely to make novels, novellas, novelettes and short stories available for free for convention attendees and sponsors (a supporting membership is only $50), we do not believe graphic novels will be included in that reader packet. Consequently, you will need to find some online (two are free) and purchase/borrow/check out others, if you want to read them all.

The fifth in our series of Hugo Voting articles (short story, novelette, novella, and related work preceding) is Best Graphic Story. Like Best Novel and Best Related Work, these books are rarely available online for free, but that is not without exception. Although the Hugo committee is likely to make novels, novellas, novelettes and short stories available for free for convention attendees and sponsors (a supporting membership is only $50), we do not believe graphic novels will be included in that reader packet. Consequently, you will need to find some online (two are free) and purchase/borrow/check out others, if you want to read them all.

-

Digger, by Ursula Vernon is a webcomic, so may be read online for free. If you’d rather own the paper comic, each volume is about ten bucks, give or take, on Amazon.

-

Schlock Mercenary: Force Multiplication is also online for free and begins here. Although dead tree versions of Schlock Mercenary are available, Force Multiplication does not seem to be in print, yet.

-

Locke & Key Volume 4: Keys To The Kingdom, is in print, and the nominated volume 4 may be found at your local comic book shop or on Amazon or in electronic format on Comixology. If you’d like to start from the beginning, get volume 1.

-

Fables Vol 15: Rose Red also does not appear to be available online. Volume 15 is $12, or you could start the whole series in dead tree or Kindle formats. The ebooks are formatted only for the Kindle Fire or Kindle for Android, however.

-

The Unwritten (Volume 4): Leviathan is also available in print and Kindle editions, but volume 4 (the volume that was nominated) is only available in print, so far.

If any more of these volumes become available for free online, we will update this post.

Links to all of the award winning novels are, as always, available through BookTrackr.

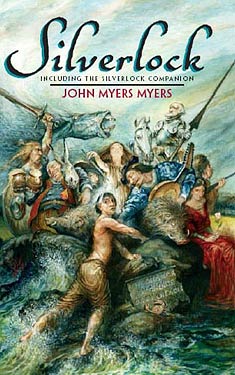

Forays into Fantasy: Silverlock by John Myers Myers

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State College in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. Recently, he began branching out into fantasy, and was surprised by the diversity of the genre. It’s not all wizards, elves, and dragons! Scott’s new blog series, Forays into Fantasy, is an SF fan’s exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, building up an understanding of the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

John Myers Myers‘s Silverlock, published in 1949, is a recursive fantasy–a fantasy that makes use of settings or characters created by other authors, emphasizing the mutual influence and interrelatedness of all literature. Myers takes this conceit to its extreme, setting the novel on an island known as the Commonwealth–a reference to our shared inheritance of fictional and historical stories referred to by Joseph Addison as the "commonwealth of letters." In the Commonwealth, all stories coexist. The setting of Silverlock is all of literature and history!

John Myers Myers‘s Silverlock, published in 1949, is a recursive fantasy–a fantasy that makes use of settings or characters created by other authors, emphasizing the mutual influence and interrelatedness of all literature. Myers takes this conceit to its extreme, setting the novel on an island known as the Commonwealth–a reference to our shared inheritance of fictional and historical stories referred to by Joseph Addison as the "commonwealth of letters." In the Commonwealth, all stories coexist. The setting of Silverlock is all of literature and history!

In the first few chapters, Clarence Shandon, traveling on the Naglfar (the ship piloted by Loki during Ragnarok in Norse mythology), is shipwrecked. Assisted by Golias, who will become Shandon’s friend and guide, and who is also adrift in the ocean for reasons unknown, they witness the appearance of Moby Dick sinking the Pequod, after which they are able to make their way to the island of Aeaea, off the coast of the Commonwealth. Aeaea is the home of Circe (see Greek mythology for the details), who turns Shandon into a pig after he makes a pass at her. Golias helps him escape the island (and the influence of Circe’s spell), and they manage to swim to Robinson Crusoe’s island, where they are nearly captured by cannibals. Escaping in one of their kayaks, they nearly die of thirst before being picked up by a Viking ship, on their way to fight in the Battle of Clontarf (which took place when the Vikings invaded Ireland in 1014). Shandon is recruited as a rower, and he and Golias end up participating in the battle, barely escaping when the Vikings are routed. Separated from Golias, Shandon (now known as Silverlock, after the streak of premature gray in his hair) soon encounters Robin Hood and his men, helps Rosalette (a composite of Rosalind from As You Like It and Nicolette from the thirteenth-century French chantefable Aucassin and Nicolette) reunite with her lover, and joins the Mad Tea Party from Alice in Wonderland, among other adventures. After these travels, he manages to rendezvous with Golias, who is found in a tavern with Beowulf, celebrating the destruction of Grendel.

And all of this happens in the first third of the book. It’s the kind of novel that’s difficult to summarize without recounting too much detail, since it is so packed with incident and character, but I wanted to provide a taste of what the reading experience is like, and the way Myers combines story elements. A summary of the plot details, however, really misses the point. Instead, consider the main character. Shandon is a prototypical mid-twentieth century pragmatic American. When he is shipwrecked, he has little interest in saving himself, having become cynical and uninterested in life. "My only philosophy, if you could call it that, had been a contempt for life backed by a pride in that contempt." He is an educated man, but is clearly not the type to spend time with trivialities like art and literature. His arrival in the Commonwealth, however, plunges him into the world of stories, where he is ultimately transformed and enlightened by his exposure to the world of literature and history–in other words, the essence of human experience–and learns to reconnect with his humanity and regain a zest for living.

It’s not an easy path. At first he resists Golias’s attempts to involve him in his adventures. (I should note that Golias is a composite of various bard, minstrel, poet, and storyteller characters, and is referred to by many names throughout the novel.) He reluctantly agrees to assist a friend of Golias to claim his love and regain his inheritance, shamed into it by the presence of Beowulf, the ultimate hero. "Remembering what he had done to help out strangers, I simply could not let him hear me say that I would back out on a friend who was asking my help." The reform of his character has begun. The subsequent picaresque adventure occupies the second third of the novel, during which many other literary and historical figures are encountered. (Favorite incidents include an attempt to placate Don Quixote, and a trip on Huck Finn’s raft).

Mission accomplished, Golias unexpectedly tells Silverlock that they must separate. Shandon, who has finally gotten used to taking pleasure in the company of others, and thinks of Golias as his new best friend, doesn’t take it well, and his selfish reaction indicates that he still has some things to learn. Continuing to wander through the Commonwealth on his own, feeling bitter and cynical, his encounters become increasingly dark. He takes a ride on the Ship of Fools, runs into Job from the Old Testament (whose suffering makes it more difficult for Silverlock to feel sorry for himself), and is taken down into the Pit by "Faustophelese," where he encounters numerous examples of the dark side of human nature, along with other hellish denizens from various mythologies and Dante’s Inferno. His soul in danger, Silverlock is again rescued by Golias, now in the guise of Orpheus, and sent to drink from the spring of Hippocrene, the well of poetic inspiration in Greek myth. He doesn’t achieve the status of poet, but drinking from the spring allows him to remember his experiences in the Commonwealth, and receive passage back to his own world. He is taken aloft by Pegasus, and dropped into the ocean to be picked up by a passing ship.

Silverlock, then, is an allegory, but it’s much more fun than A Pilgrim’s Progress, as it includes much more drinking and singing. Shandon regains the joy of life, and Myers portrays that joy throughout. It’s a novel that shouldn’t work, yet does, and I put this down to the novel’s unique narrative perspective. The Commonwealth is not a fantasy setting in the usual sense. Those who read fantasy for the world-building aspect are likely to be disappointed, because this world makes no sense. Stories and characters from different historical periods coexist side by side, but the Vikings fight with bows, spears, and longships, oblivious to the fact that guns and steamboats are being used a few miles away. When Shandon encounters all of these characters and settings, he accepts them, never bringing up the fact that they are from stories. His pragmatic mind simply accepts the Commonwealth for what it is, and he never considers that his encounters seem designed to teach him lessons in living. This method allows the story to exist on several levels. The novel is narrated by Shandon, and from that direct perspective, Silverlock is a rollicking, rapidly-paced adventure story, full of excitement and interesting encounters, and can be enjoyed as such by readers mostly unaware of the literary allusions.

But for the reader with literary experience, those allusions provide another level of enjoyment. Since events are being described by someone entirely unfamiliar with the original stories, the reader must often identify the allusions without characters and settings being directly mentioned, but only described. For example, at one point Shandon and Golias find a raft and use it to travel toward their destination more quickly than they could on foot. The description of the river and their feelings while on the raft will identify it pretty quickly to anyone who has read Huckleberry Finn, but that story is never mentioned. Encountering Robin Hood or Don Quixote, Shandon doesn’t react by remembering the characters from a book or a movie, but his descriptions of their appearance and behavior will identify them to those familiar with the stories.

And I can guarantee that no reader will be familiar with all the stories. Nearly every detail in the book is taken from another story. Knowing that, I found myself continually trying to figure out the sources based on the descriptions in the novel, since they are not directly identified, and are often composites of similar characters from different stories (as in the case of Golias). This literary guessing game will be an enjoyable challenge for some readers, and is a big reason for the book’s cult following. Anyone trying to "get" all the references is bound to be disappointed, but the wonderful thing about Myers’s narrative method is that the novel can be enjoyed without getting them, so the reader can engage with that aspect of the novel to whatever degree she cares to.

And I can guarantee that no reader will be familiar with all the stories. Nearly every detail in the book is taken from another story. Knowing that, I found myself continually trying to figure out the sources based on the descriptions in the novel, since they are not directly identified, and are often composites of similar characters from different stories (as in the case of Golias). This literary guessing game will be an enjoyable challenge for some readers, and is a big reason for the book’s cult following. Anyone trying to "get" all the references is bound to be disappointed, but the wonderful thing about Myers’s narrative method is that the novel can be enjoyed without getting them, so the reader can engage with that aspect of the novel to whatever degree she cares to.

For anyone thinking of reading Silverlock, I strongly recommend getting the NESFA Press edition, which is still in print, since, along with being a beautiful book, it contains The Silverlock Companion, a hundred and fifty pages of supplementary material including, most importantly, "A Reader’s Guide to the Commonwealth," a concordance of the literary allusions. Coming across an unfamiliar character or place, it can be looked up in the guide and the original source identified. Along with discovering literary antecedents I was unaware of, or only vaguely aware of, this additional background added to my understanding of Myers’s reasons for choosing the stories for Silverlock to interact with, in relation to his own progress as a character. Browsing through this compendium of eighteenth and nineteenth century novels, Greek, Norse, Irish, Icelandic, and Chinese myths and legends, American tall tales, and Old English poetry, Myers’ amazing achievement is brought home. (And those examples just scratch the surface. There are hundreds of stories referenced in Silverlock.) His goal, however, is not to point out his own erudition, but rather to celebrate the role of stories in our lives. His story–Silverlock–is just one more small region to be annexed by the Commonwealth. Instead, he wants to remind us of the beauty–dramatic, comedic, tragic, romantic, fantastic–of the literary and historical heritage of humanity. Like Shandon, we can’t stay in the Commonwealth forever, but visiting it will enrich our lives by providing access to people, ideas, and experiences that enrich our understanding and enjoyment of life.

So, where does Silverlock fit in the history of fantastic literature? As mentioned above, it can be seen as a major exemplar of recursive fantasy, and many of its sources are the wellsprings of the fantastic–ancient myths, fairy tales, Arthurian legends, Beowulf, Dante’s Inferno…–thus being in a sense a fantasy about the fantastic. But since the narrator, Shandon, is unaware of the nature of the fantasy world he has entered, it does not come across as self-aware metafiction. As far as I know, then, Silverlock is unique in the history of fantasy. While there are plenty of other examples of recursive fantasy (Myers was probably influenced by L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt’s Incomplete Enchanter, for example), none that I know of operate in the way the Silverlock does. (If anyone knows of anything similar, I’d like to hear about it.)

Its uniqueness may explain its relative obscurity. As Myers wrote in 1980: "This was to be my big book, my contribution to the ages, and it flopped all over the place. Although it has since been revived by Ace in 1966, and again in 1979–it was an egg laid by an ostrich when it first came out and was remaindered." It’s been championed by its fans–Poul Anderson, Larry Niven, and Jerry Pournelle each wrote introductions to the 1979 edition–but it seems to be something of a cult item today, not well known to the community of fantasy readers, but extremely well-loved by those who do know it and appreciate it. According to David Pringle, who includes it in his Hundred Best, Myers "has produced a strange, harshly whimsical and rumbustious book… It will not be to every reader’s taste, but it is memorably different."

Its lack of success may have had to do with its timing. Prior to the 1920s, fantasy as a genre had yet to be ghettoized. Hawthorne, Melville, Henry James, Mark Twain, and Jack London all wrote fantasy without readers raising an eyebrow. It was just one of a number of fictional strategies used by these writers. By the time Silverlock was published, however, fantasy had mostly been relegated to the pulps. Silverlock, as a literary fantasy arriving in 1949, was ignored by the mainstream, simply because it was fantasy, while not being the sort of thing to interest the majority of the genre audience. In retrospect, we can ignore the genre prejudices and see it as part of a larger flowering of fantasy in the ‘40s and ‘50s that included, in America, de Camp and Pratt, Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser sequence; and, in the United Kingdom, Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast trilogy, C. S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia, and, of course, J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. Despite being the least well-known of these contemporaries, it deserves to be considered among them.

GMRC Review: The Brothel in Rosenstrasse by Michael Moorcock

Rhonda Knight is a frequent contributor to WWEnd through her many reviews and her excellent blog series Automata 101 and Outside the Norm. This is Rhonda’s fifth featured review for the Grand Master Reading Challenge. She won the GMRC Review of the Month for March for her review of The Word for World is Forest by Ursula K. Le Guin.

Rhonda Knight is a frequent contributor to WWEnd through her many reviews and her excellent blog series Automata 101 and Outside the Norm. This is Rhonda’s fifth featured review for the Grand Master Reading Challenge. She won the GMRC Review of the Month for March for her review of The Word for World is Forest by Ursula K. Le Guin.

In my attempt to combine some of my reading challenges, I decided to read Michael Moorcock‘s The Brothel in Rosenstrasse for the GMRC. The "brothel" in the title fulfills the "house" requirement in Beth Fish’s Readers Challenge. Before I chose this book, I did a little research and learned that the book was the second in Moorcock’s Rickhardt von Bek trilogy but that I need not read the first book before reading the second.

In my attempt to combine some of my reading challenges, I decided to read Michael Moorcock‘s The Brothel in Rosenstrasse for the GMRC. The "brothel" in the title fulfills the "house" requirement in Beth Fish’s Readers Challenge. Before I chose this book, I did a little research and learned that the book was the second in Moorcock’s Rickhardt von Bek trilogy but that I need not read the first book before reading the second.

Von Bek is the first person narrator of the novel. As a sick, bedridden old man, von Bek writes a memoir about his secret affair with the sixteen-year-old, Alexandra, a daughter of a noble family. This affair took place in fin de siècle Mirenburg, a city located in the fictional central European nation of Waldenstein. Moorcock creates a lush, cosmopolitan, multicultural city, where Europeans come to enjoy the cafés, cabarets, opium dens, and, of course, the brothel, "Mirenburg’s greatest treasure," "protected by every authority and tolerated by the Church" (45). Unfortunately, the architectural beauty and joie de vivre of Mirenburg is destroyed by a civil war during the course of the book.

Before the war comes, Alexandra and von Bek live together in the Liverpool Hotel and take advantage of the lax stewardship of Alexandra’s parents (who are out of the country), her aunt (who is supposed to be responsible for Alexandra in their absence but farms her off to the housekeeper, who is tricked by her charge). Von Beck is infatuated by Alexandra but is also repulsed by her extreme willingness to play the role of his sex toy. He justifies his lifestyle as a debaucher and rake by writing "I live as I do because I have no need to work and no great talent for art; therefore my explorations are usually in the realm of human experience, specifically sexual experience, though I understand the dangers of self-involvement in this as in any other activity" (94). In order to keep his pupil Alexandra interested, von Beck begins taking Alexandra to the brothel, where they engage in threesomes, foursomes, sadomasochism and cocaine use.

When the war comes, Alexandra tells her family that she and her friends are joining refugees outside the city but instead she and von Bek are forced to seek refuge in the brothel once their hotel is bombed. Von Bek describes the brothel as "an integrated nation, hermetic, microcosmic" (49). However, while von Bek enjoys the clubby atmosphere of the salon and the dining table, Alexandra must hide in their room because they cannot risk her being recognized by another member of the nobility. Once von Beck relents and lets Alexandra appear, she begins to manipulate the citizens of the microcosm as the long siege of Mirenburg begins.

Von Bek’s memoir slips between his past in Mirenburg and his present as an invalid whose only human contact is with his manservant. Moorcock handles this in an interesting way as von Bek’s arguments (both vocal and silent) with the manservant Papadakis weave in and out of the memoir:

I can only admit now that I gave myself up to Eros deliberately, in the belief it does a man or woman good to make such fools of themselves occasionally, there are few risks much wilder and few which make us so much wiser, should we survive them. Papadakis stretches out his emaciated arms. I smell boiled fish. "It will do you good," he says in his half-humorous, half-insinuating voice; a voice once calculated during his own, brief Golden Age to rob the weak of any volition they might possess; but it had been the single weapon in his arsenal; he had used up all of his emotional capital by the time he was forty. (38)

Von Bek’s writing demonstrates his insecurity concerning Alexandra in the past and his fear of death in the present. The narrative has the fury of a man writing against time and to regain his past. He alternates between scenes of sexual excess and lush description that shows his love of Mirenburg, which he loves as much as Alexandra.

Von Bek’s writing demonstrates his insecurity concerning Alexandra in the past and his fear of death in the present. The narrative has the fury of a man writing against time and to regain his past. He alternates between scenes of sexual excess and lush description that shows his love of Mirenburg, which he loves as much as Alexandra.

There are no fantasy or supernatural elements in this book. Only Moorcock’s name and the fact that Rickhardt von Bek’s ancestor Ulrich is the protagonist of The War Hound and the World’s Pain connect The Brothel in Rosenstrasse to the fantasy genre; this book is a historical romance focusing on decadence and obsession. Unless WWE readers are also interested in historical fiction, I’d recommend this one for Moorcock completists only. The plot is thin, and the characters are weak and not really likeable. The city of Mirenburg is the star: the descriptions of the city are beautiful and his ability to situate the reader in a location is dazzling. I am looking forward to reading the other two books in the series but hope they are more driven by character and plot.

Moorcock has made his fictional brothel famous not only through the book but through song. The song was recorded by Michael Moorcock and Deep Fix in 1982. You can hear it on YouTube.

The lyrics are as follows:

Schmetterling says that all her girls are ladies

She won’t hand out keys to anyone who’s shady

It’s all done with taste, you must not seem a waster or a scoundrel

She’s kind and she’s warm, believes in good form

So don’t be hasty!The Brothel in Rosenstrasse all our girls are clean and game

The Brothel in Rosenstrasse, you don’t have to give your right namePlease don’t speak of despair, or anything that’s seedy

Please don’t admit you’re cynical and greedy

Your manner’s refined, your role is clearly defined, and so is the lady’s

The things that you do aren’t wicked or rude, because you need themThe Brothel in Rosenstrasse, all our girls are keen to please

The Brothel in Rosenstrasse, at reasonable fees

Forays into Fantasy: The Castle of Otranto, the Gothic Novel and the Origins of Fantasy

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State College in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. Recently, he began branching out into fantasy, and was surprised by the diversity of the genre. It’s not all wizards, elves, and dragons! Scott’s new blog series, Forays into Fantasy, is an SF fan’s exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, building up an understanding of the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

As my interest in science fiction was revived over the last couple of years, and I decided to expand my reading into fantasy as well, I went in search of context. Looking for a guide to some superior and important examples of fantasy, beyond the usual suspects, I pulled David Pringle’s Modern Fantasy: The Hundred Best Novels off the shelf (and examples of some of these novels will continue to show up in this series of posts), but Pringle begins in 1946, and I wanted to start at the beginning. Fantasy: The 100 Best Books, by James Cawthorn and Michael Moorcock, published in 1988, starts in the eighteenth century. Specifically, the first book listed is Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift (1726) — no surprise there. The other three examples from the 1700s, though, I had never heard of before: The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole, Vathek by William Beckford, and The Monk by Matthew Gregory Lewis. Upon reading Cawthorn and Moorcock’s essays, it became clear that these were all examples of early Gothic novels, which make up one of the earliest strands of the fantasy genre.

As my interest in science fiction was revived over the last couple of years, and I decided to expand my reading into fantasy as well, I went in search of context. Looking for a guide to some superior and important examples of fantasy, beyond the usual suspects, I pulled David Pringle’s Modern Fantasy: The Hundred Best Novels off the shelf (and examples of some of these novels will continue to show up in this series of posts), but Pringle begins in 1946, and I wanted to start at the beginning. Fantasy: The 100 Best Books, by James Cawthorn and Michael Moorcock, published in 1988, starts in the eighteenth century. Specifically, the first book listed is Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift (1726) — no surprise there. The other three examples from the 1700s, though, I had never heard of before: The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole, Vathek by William Beckford, and The Monk by Matthew Gregory Lewis. Upon reading Cawthorn and Moorcock’s essays, it became clear that these were all examples of early Gothic novels, which make up one of the earliest strands of the fantasy genre.

So, did fantasy as a genre really begin in the 1700s (clearly, there was fantastic literature prior to that), and what role did these Gothic novels play in those beginnings? During this eighteenth century, poets and philosophers debated the nature of imagination, and there was a new and rising view that the imagination was not merely a repository of memory and observation, but was a faculty capable of the visionary illumination of the unknown, as Samuel Coleridge and William Blake tried to do in their poetry. In literature, these ideas led to the ongoing distinction between the realistic and the fantastic. As Gary K. Wolfe writes in “Fantasy from Dryden to Dunsany,” in The Cambridge Companion to Fantasy Literature (2012):

“The modern fantasy novel, and to an arguable extent the modern novel itself, is in part an outgrowth of this debate. While we can reasonably argue that the fantastic in the broadest sense had been a dominant characteristic of most world literature for centuries prior to the rise of the novel, we can also begin to discern that the fantasy genre may well have had its origins in these eighteenth- and nineteenth-century discussions of fancy vs. imagination, history vs. romance…”

In particular, Wolfe sees the fantasy genre as arising from three sources during the 1700s and 1800s: “private history” novels such as Robinson Crusoe, a revival of interest in old folk tales and fairy tales, and the vogue for Gothic novels, all three of which required the use of imagination to envision what we now think of as “the fantastic.”

Where, then, did this Gothic strand of literature arise from, and what does it entail? Our story begins during the latter stages of the Roman Empire, when the Goths pillaged their way south from Scandinavia, ultimately sacking Rome in 410. After gaining control of the Italian peninsula, they eventually lost power later in the Middle Ages, after sundry violent run-ins with the Huns, the Franks, and the Moors. Due to its association with the decline of the Classical world, the term “Gothic” came into use during the 1500s as a pejorative term for a medieval style in art and architecture, from the twelfth — through the sixteenth — centuries, which was considered during the Renaissance to be ugly and barbaric when compared to the Classical art and architecture it supplanted. It is best represented by the intricate and sculpturally adorned Medieval cathedrals with their soaring pointed arches, which took advantage of advances in structural design to achieve previously unprecedented height, with correspondingly tall windows and, of course, lots of gargoyles.

Where, then, did this Gothic strand of literature arise from, and what does it entail? Our story begins during the latter stages of the Roman Empire, when the Goths pillaged their way south from Scandinavia, ultimately sacking Rome in 410. After gaining control of the Italian peninsula, they eventually lost power later in the Middle Ages, after sundry violent run-ins with the Huns, the Franks, and the Moors. Due to its association with the decline of the Classical world, the term “Gothic” came into use during the 1500s as a pejorative term for a medieval style in art and architecture, from the twelfth — through the sixteenth — centuries, which was considered during the Renaissance to be ugly and barbaric when compared to the Classical art and architecture it supplanted. It is best represented by the intricate and sculpturally adorned Medieval cathedrals with their soaring pointed arches, which took advantage of advances in structural design to achieve previously unprecedented height, with correspondingly tall windows and, of course, lots of gargoyles.

As pointed out by Adam Roberts in his essay on “Gothic and Horror Fiction” also in The Cambridge Companion, by the time the term “Gothic” was first used to describe a form of literature, in the mid-eighteenth century, its “primary signification… was that of barbarous anti-enlightenment.” At the same time, a revival of interest in Gothic aesthetics would result in the term becoming more complimentary in the eyes of those who began to bring the now old-fashioned medieval styles back into fashion. Among these was Horace Walpole, who rebuilt his London mansion in what he considered to be a “Gothic” style, and wrote what is generally agreed to be the first Gothic novel, The Castle of Otranto: A Story, published in 1764. (Subsequent editions would be subtitled A Gothic Story.)

Walpole originally published The Castle of Otranto under a pseudonym, claiming in the preface that it was a translation of a recently discovered manuscript printed in 1529 and most likely written between 1095 and 1243, thus pretending to establish it as an actual work of the Middle Ages. He speculates that it was written by a priest in order to “avail himself of his abilities as an author to confirm the populace in their ancient errors and superstitions” at a time when such superstitions were being challenged by the Italian intelligentsia. Although presented by the translator as a mere entertainment:

“Some apology for it is necessary. Miracles, visions, necromancy, dreams, and other preternatural events, are exploded now even from romances. That was not the case when our author wrote; much less when the story itself is supposed to have happened. Belief in every kind of prodigy was so established in those dark ages, that an author would not be faithful to the manners of the times, who should omit all mention of them. He is not bound to believe them himself, but he must represent his actors as believing them. If this air of the miraculous is excused, the reader will find nothing else unworthy of his perusal. Allow the possibility of the facts, and all the actors comport themselves as persons would do in their situation… Terror, the author’s principal engine, prevents the story from ever languishing; and it is so often contrasted by pity, that the mind is kept up in a constant vicissitude of interesting passions.”

Clearly, Walpole was aware of the debate over the role of imagination in literature described above by Wolfe, and was attempting to combine the virtues of the modern novel with the fanciful content of ancient stories and myths. Ironically, while claiming to apologize to the reader for the old-fashioned fantastical elements in the story, what Walpole was really doing, by bringing these elements into a novel, was to create something entirely new. In the Middle Ages, people really were superstitious, and such stories would not have been considered “fantastic” in the modern sense. By the 1700s, by which time the Enlightenment had banished superstition from the educated mind, bringing back the fantastic required a new use of imagination for both writers and their audience.

Clearly, people were ready for it. In a popular and commercial sense, his experiment was very successful, unleashing a sea of imitators. Despite Walpole’s apology for it, it is that very “air of the miraculous” that makes the novel intriguing. The plot itself is quite ludicrous, but individual incidents, and the overall mood, keep things interesting. Manfred, lord of the Castle of Otranto, while overseeing the wedding of his sickly son Conrad to Isabella, is shocked and dismayed when a giant helmet appears and crushes Conrad to death, leaving Manfred without an heir. The enormous helmet is otherwise identical to that once worn by Alfonso the Good, who is supposed to have granted the castle to Manfred’s grandfather many years before. Clearly concerned about the implications of this strange event, and determined to maintain his family’s succession, he announces his intention to divorce his wife Hippolita, who has been incapable of providing him with another son, and marry Isabella himself. Neither woman is pleased. Isabella escapes with the help of Theodore, whom Manfred sentences to death. Chasing Theodore and Isabella into the vaults beneath the castle, Manfred encounters an apparition of his grandfather, as well as manifestations of giant armored body parts and weapons, presumably arising from the same source as the helmet. As Manfred had feared, these visions herald the fulfillment of a prophecy that foretold the end of his family’s usurpation of the castle, and the return of its rightful heir, who turns out to be Theodore. Isabella ends up Queen of the castle after all.

Clearly, people were ready for it. In a popular and commercial sense, his experiment was very successful, unleashing a sea of imitators. Despite Walpole’s apology for it, it is that very “air of the miraculous” that makes the novel intriguing. The plot itself is quite ludicrous, but individual incidents, and the overall mood, keep things interesting. Manfred, lord of the Castle of Otranto, while overseeing the wedding of his sickly son Conrad to Isabella, is shocked and dismayed when a giant helmet appears and crushes Conrad to death, leaving Manfred without an heir. The enormous helmet is otherwise identical to that once worn by Alfonso the Good, who is supposed to have granted the castle to Manfred’s grandfather many years before. Clearly concerned about the implications of this strange event, and determined to maintain his family’s succession, he announces his intention to divorce his wife Hippolita, who has been incapable of providing him with another son, and marry Isabella himself. Neither woman is pleased. Isabella escapes with the help of Theodore, whom Manfred sentences to death. Chasing Theodore and Isabella into the vaults beneath the castle, Manfred encounters an apparition of his grandfather, as well as manifestations of giant armored body parts and weapons, presumably arising from the same source as the helmet. As Manfred had feared, these visions herald the fulfillment of a prophecy that foretold the end of his family’s usurpation of the castle, and the return of its rightful heir, who turns out to be Theodore. Isabella ends up Queen of the castle after all.

The genre ushered in by Walpole’s story remained very popular until about 1820, and continued to evolve thereafter (think of Frankenstein, Wuthering Heights, Dracula, and Rebecca). Very few of the novels from the original flowering of the Gothic are still read, but they represented an unleashing of imaginative literature that would ultimately lead to the development of the modern genres of horror (which still maintains an explicitly gothic strand), fantasy, and even science fiction, whose readers are often looking for the same “sense of wonder” as was the original audience for gothic fiction.

The characteristic feeling evoked by the Gothic story is the combination of the familiar and the foreign — the simultaneous attraction and repulsion that Freud wrote about as “the uncanny.” This characteristic of the Gothic has to do with the mood rather than the well-known trappings of the stories — the feeling of mysteriousness, that there are things happening that we can’t quite understand and that may ultimately remain obscure; that important realizations are just out of reach in the shadows and gloom. The reader wants to find out what horrors (usually evils from the past returning to haunt the present) underlie the events in the story, but at the same time is afraid to find out.

The typical elements of the settings in which these strange stories play out have become iconic. As Adam Roberts explains:

“In Otranto we find, in nascent form, many of the props and conventions that were to reappear in the scores of novels published at the height of the Gothic vogue…: moody atmospherics, picturesque and sublime scenery, darkness, buried crimes (especially murderous and incestuous crimes) revealed, and most of all a spectral supernatural focus. Many imitators tried to follow Walpole’s commercial success by littering their novels with similar props, settings and conventions — the haunted castle, the night-time graveyard, the Byronic villain and so on,”

But the elements that make the works successful are not these outward trappings, but rather their ability to invoke the uncanny and the transgressive, and to fire the reader’s imagination.

But the elements that make the works successful are not these outward trappings, but rather their ability to invoke the uncanny and the transgressive, and to fire the reader’s imagination.

As for Otranto in particular, it is the first, but not the very best. Fantasy readers today will have no problem with the fantastic elements, but may struggle with the improbable plot twists, many of which hinge on mistaken or hidden identity, and with the overwrought dialogue. Those willing to make allowances, however, will be carried along by the onrushing events and the feverish intensity of the characters’ emotions and actions, until the situation they are caught up in is finally resolved. These events, manifested through supernatural interventions into the real world, were precipitated by past injustice, a pattern which will play out again in subsequent Gothic novels, often within some variation on Walpole’s shadowy castle and subterranean vaults, literary images that have never ceased to haunt readers of the fantastic.

Next: More early Gothic novels will be reviewed in a future post, but up next is a 1949 American fantasy novel set in a land where stories are real: Silverlock by John Myers Myers.

Power resides where men believe it resides.

Game of Thrones season 2 starts tonight! Watch it and come back here and let us know what you think.

Review: The Warded Man by Peter V. Brett

Guest Blogger and WWEnd Member, Matt W. (Mattastrophic), reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Strange Telemetry. Matt is a regular WWEnd contributor and he won the January GMRC Review of the Month for his review of The Dispossessed. Check out his profile page for more great reviews or visit his blog and let him know you found him here.

Note: The Warded Man is published in the UK as The Painted Man.

The demons rise every night without fail, and every night a few more humans are viciously killed. The only thing that can hold them at bay are the magical wards people put around their homes, and within which they huddle together at night, trying to ignore the sounds of the monsters outside constantly looking for a way in. Some of them find it. When the corelings–demons of fire, rock, air,water, sand, and rot–first rose, they massacred humans close to the point of extinction. Then mankind discovered the magical combat wards that allowed them to fight the beasts. An unparalleled age of science and progress followed, but safety bred complacency, and when the corelings returned mankind fell into a dark age and lost a great deal of knowledge about the wards. Now, during the day men and women work and check their defensive wards, while at night all they can do is huddle in their homes and hope the defenses will hold and keep the monsters out. Travel between townships is minimal, and few know the world beyond their own hometown. Much has been lost, and much continues to be lost as every night as a few more people succumb to the corelings.

The demons rise every night without fail, and every night a few more humans are viciously killed. The only thing that can hold them at bay are the magical wards people put around their homes, and within which they huddle together at night, trying to ignore the sounds of the monsters outside constantly looking for a way in. Some of them find it. When the corelings–demons of fire, rock, air,water, sand, and rot–first rose, they massacred humans close to the point of extinction. Then mankind discovered the magical combat wards that allowed them to fight the beasts. An unparalleled age of science and progress followed, but safety bred complacency, and when the corelings returned mankind fell into a dark age and lost a great deal of knowledge about the wards. Now, during the day men and women work and check their defensive wards, while at night all they can do is huddle in their homes and hope the defenses will hold and keep the monsters out. Travel between townships is minimal, and few know the world beyond their own hometown. Much has been lost, and much continues to be lost as every night as a few more people succumb to the corelings.

Three young people from different towns in this perilous world set off on paths that will eventually converge, and which may eventually lead them to some measure of hope and salvation for mankind. Arlen is a young boy with a knack for wards who has become sick at everyone’s cowardice and lack of resolve to fight the demons. Leesha is a blossoming young woman with a talent for herb gathering and healing, making her a keeper of some of the oldest surviving tradition, lore, and medicine from the days before the corelings return. But a nasty rumor and a town scandal threatens her. Rojer always wanted to be jongleur, a wandering musician and performer who is the delight of every town he passes through (and who brings rare rays of sunshine and joy into this otherwise bleak world). When demons attack his home and he is horribly maimed, that dream is threatened, but eventually he discovers he has a talent for music that goes beyond mere entertainment. Each has been scarred by the demons, and the book follows their growth from childhood to adulthood.

This is the premise of The Warded Man, by Peter V. Brett, which is yet another book that made me think “fah, what crap” when I first saw it. I guess at the time I was put off by what I have noticed is a pretty formulaic title: The (insert adjective here) Man, as in The Demolished Man, The Illustrated Man, The Female Man, The Invisible Man, The Unincorporated Man, The Thin Man, ad inifinitum. Once I got over my title prejudice and took a close gander at the blurb, I was seized by the interesting premise. It put me to mind of the dark ages following the fall of the Roman Empire, when knowledge was lost and the world grew smaller, darker, and scarier, and having just seen a documentary on the dark ages the premise of this book grabbed me at the right moment. After checking out a few reviews of the book, I decided to give it a shot; I had a spare Audible credit at the time, and I was keeping my expectations flexible. To my surprise, I was really sucked into this book, and once again I found that (ugh) you can’t judge a book by its cover (thank you every elementary school teacher I ever had).

Strong Magic: What The Warded Man Does Well

Brett has stated that he really wanted to write a book about fear and it’s effect on people, and in this YouTube interview he links that desire to his experience with 9/11 and it’s aftermath. The fear angle really comes out in this novel. It is strong in the first thread, Arlen’s, where the young boy learns contempt for his own father’s cowardice before the demons. Much of the worldbuilding Brett does revolves around fear of the corelings and the precautions taken to stay safe from them, which fits since it is a constant, pervasive threat in a similar way fear of terrorism swept the U.S. following 9/11. The night is a time of danger and fear for the people of Brett’s novel, so much so that “night!” has become a curse word. Brett has showed how fear of the corelings has affected everything from architecture and city planning to the way cities and societies have become more insular. Messengers, who travel from town to town bearing supplies and act as diplomats and emissaries, are raised to heroic status for braving the open night between towns with nothing but a portable warding circle between them and the monsters. People have become resigned to living in this world, with only one group, the desert people to the south, actively fighting the monsters. Overall, the atmosphere this creates has an appropriate dark ages feel, similar to what happened after the fall of Rome: technology and knowledge has been lost, and the world suddenly grows a lot smaller and a lot scarier.

The characterization is very good as well. Thankfully, it’s is not filler in between action scenes. The demons are catalysts and background for the tragedies and rites of passage that each character struggles with as they grow up, and their circumstances and character arcs makes them feel like distinct, believable characters. I lost myself (in a good way) in the stories of each of the three viewpoint characters, and even when they were not dealing with the demons their stories were still exciting, tense, and interesting. Will Arlen find a way to fight the demons, or is it only a boy’s fantasy? Can he ever settle for a normal life, one with a wife and children? Will Leesha ever get past the stigma put on her by that nasty rumor, and finally be able to move on with her life? Will she ever be rid of her domineering mother? Will Rojer be able to hang on to his dream of being a jongleur given his maimed hand and his now drunkard of a mentor? Their life experiences feel true to the human condition given such an environment, and like George R. R. Martin’s books (which Brett cites as a major inspiration) the situations they are in frequently offer no easy out or simple moral choice. Each viewpoint character feels well-realized, so that when they eventually come together their relationships with one another is dynamic and interesting.

While the characterization is not just filler between the action, that doesn’t mean that the action is disregarded or underdeveloped. The action works pretty well, especially the climax of the book. There are very few ways to fight the demons, who can shrug off the attacks of most weapons and heal rapidly, so most of the time it’s a desperate struggle for survival and a dash for safety. When a character is caught out at night and trying to find shelter from the monsters, the narrative puts you on the edge of your seat.

Finally, while this book has some very dark places, there is the thread of hope that Brett nurtures along the narrative: hope of turning the tide in the fight against the demons, hope of the people finding courage instead of despair, hope that characters will find their dreams, etc. My one major problem with dystopian or apocalyptic narratives is that the bleakness of them can be a real turnoff. The Warded Man shares elements of the latter genre, although it is squarely fantasy, but thankfully the bleakness does not overwhelm the narrative. Normalcy has a way of asserting itself in the midst of prolonged disaster, and Brett does a good job of showing how each character finds hope and pursues dreams and ambitions both because of and despite the nightly dangers of the demons.

Faded Wards: Where The Warded Man Could Have Been Better

While the fear people feel for the coreligns is very well established in the prose and the interpersonal interactions of characters, the demons themselves failed to dazzle or horrify). The monsters are not particularly well described in the beginning, and while I would certainly not want to be trapped outside with any of them, they didn’t scare me all that much. I kept thinking back to how Jim Butcher describes monsters, how, even when seen full view, I not only had a better idea of what they looked like and what distinguished them, but why they were frightening as well. In most monster stories, the monsters lose some pzzazz after they are revealed in full. Perhaps since Brett was revealing the mosnters very early on, they never seemed very scary. It may also be that they lost some of that oompf by being such a common sight. Still, given that they were so central to the conceit of the novel, I was a bit disappointed in their presentation.

As mentioned earlier, Brett has stated that he really admires George R. R. Martin, and that the moral complexity Martin brings to his characters has caused Brett to really bring up the level of his own writing. Like Martin, the world that Brett creates is filled with ugly, immoral people who will kill you as soon as look at you, but it’s almost too full of those characters. There are characters who help and support the viewpoint characters and characters who are unambiguously bullies or just plain evil, and I didn’t sense that there was a whole lot of a middle ground. The bullies and evil characters are frequently, and obviously, foils for the development of the viewpoint characters, but after a while the presence of a bully/rapist (or would-be rapist)/opportunist who has bad intentions on our main characters stopped being surprising and started feeling like a matter of course. Things start to feel soap-opera-ish at times. While Brett does complicate our view of one bully character greatly in the climax of this book, I sense that I will have to wait until future volumes to see how he wraps up the plot threads of these other characters, so I might just be rescinding this criticism later.

As mentioned earlier, Brett has stated that he really admires George R. R. Martin, and that the moral complexity Martin brings to his characters has caused Brett to really bring up the level of his own writing. Like Martin, the world that Brett creates is filled with ugly, immoral people who will kill you as soon as look at you, but it’s almost too full of those characters. There are characters who help and support the viewpoint characters and characters who are unambiguously bullies or just plain evil, and I didn’t sense that there was a whole lot of a middle ground. The bullies and evil characters are frequently, and obviously, foils for the development of the viewpoint characters, but after a while the presence of a bully/rapist (or would-be rapist)/opportunist who has bad intentions on our main characters stopped being surprising and started feeling like a matter of course. Things start to feel soap-opera-ish at times. While Brett does complicate our view of one bully character greatly in the climax of this book, I sense that I will have to wait until future volumes to see how he wraps up the plot threads of these other characters, so I might just be rescinding this criticism later.

My last criticism comes with a big damn hedging comment attached to it. I found myself wondering about other aspects of the world Brett had built since the worldbuilding only went so far. I imagine if demons started to rise every night in our world, they would take up a lot of our time and consideration, but normalcy and culture find ways of establishing and reestablishing themselves, so I was wondering about other aspects of the world that were not touched on. Of course, this lack of deep worldbuilding can be attributed to the fact that trade and communication is extremely limited by the nightly monster mash, so what would Rojer, Leesha, or Arlen know about far-flung lands? Still, I wanted to see the local culture, government, politics, etc. fleshed out in some more detail.

Concluding Thoughts

Despite some of these criticisms (which I may reverse my opinion on after reading the rest of the series), I enjoyed The Warded Man immensely. I was initially taken in by the central conceit of people barely surviving a nightly onslaught of demons and of kindling the hope to find a way to beat them back, but I stuck with the book for its characters and storytelling. Indeed, I’m pretty invested in Arlen, Leesha, and Rojer, and I really want to see what happens to them next and what happens to the world given the plot events set in motion by the epilogue! As I’ve stated in previous posts, I’m very discerning with what kind of fantasy I read. Perhaps I’m more of a fantasy snob than I am a Science Fiction snob, I don’t know, but I take greater care in picking my fantasy books. I was skeptical about this book, but I found myself hungry for a little fantasy and, given that Scott Lynch’s much-anticipated The Republic of Thieves kept suffering setbacks and that I’m still waiting for Martin’s A Dance with Dragons to come down to a reasonable price ($15 for the ebook from the kindle store? No thank you!) I took a chance on The Warded Man. It not only met and exceeded my standards, but it has put me in the mood to expand my fantasy horizons. I’ve already downloaded the sequel, The Desert Spear, but in between this review and the one for that book I am going to try the first parts of at least two other fantasy series.

In short, I recommend this book enthusiastically and am going to make Brett someone to keep my eye on in the future.

I listened to to this as an unabridged audiobook narrated by Pete Bradbury, whom I was dubious about at first. His somewhat deep voice has a kind of twang (one I can’t quite place) to it that at first didn’t seem to mesh with a fantasy story, but once I got used to it I enjoyed immensely. Come to find out that he has done a few roles on Law and Order and Criminal Intent, which makes me kick myself for not recognizing the book (being the L&O nut that I am).

Forays into Fantasy: Darker Than You Think by Jack Williamson

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State College in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. Recently, he began branching out into fantasy, and was surprised by the diversity of the genre. It’s not all wizards, elves, and dragons! Scott’s new blog series, Forays into Fantasy, is an SF fan’s exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, building up an understanding of the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

Note: This blog post also counts as a Grand Master Reading Challenge review.

Between March 1939 and October 1943, John W. Campbell edited a magazine called Unknown (later Unknown Worlds)—a fantasy companion to Astounding, which at that time was at the peak of its influence in the science fiction world. Campbell wanted to create a contrast to the uncanny horror of Weird Tales, and sought out fantasy stories with logical underpinnings for the fantastic elements, a high intellectual/literary level, and often humor. I previously reviewed A. E. Van Vogt’s The Book of Ptath, which originally appeared in the final issue of Unknown. Its extreme far-future setting left open the possibility that what we would normally take to be fantasy elements had a science fictional explanation. Other writers with backgrounds in science fiction also contributed to Unknown, including L. Ron Hubbard, Robert Heinlein, Theodore Sturgeon, and Henry Kuttner. L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt’s Harold Shea sequence (collected as The Complete Enchanter) and Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser series got their starts here as well. Jack Williamson’s “Darker Than You Think” first appeared as a novella in the December 1940 issue.

Between March 1939 and October 1943, John W. Campbell edited a magazine called Unknown (later Unknown Worlds)—a fantasy companion to Astounding, which at that time was at the peak of its influence in the science fiction world. Campbell wanted to create a contrast to the uncanny horror of Weird Tales, and sought out fantasy stories with logical underpinnings for the fantastic elements, a high intellectual/literary level, and often humor. I previously reviewed A. E. Van Vogt’s The Book of Ptath, which originally appeared in the final issue of Unknown. Its extreme far-future setting left open the possibility that what we would normally take to be fantasy elements had a science fictional explanation. Other writers with backgrounds in science fiction also contributed to Unknown, including L. Ron Hubbard, Robert Heinlein, Theodore Sturgeon, and Henry Kuttner. L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt’s Harold Shea sequence (collected as The Complete Enchanter) and Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser series got their starts here as well. Jack Williamson’s “Darker Than You Think” first appeared as a novella in the December 1940 issue.

Williamson’s career spans the history of science fiction. Born in 1908, his family traveled by covered wagon from Arizona to their New Mexico homestead, where Williamson discovered the early science fiction pulps and became entranced by imaginary worlds incredibly distant from his family’s rural ranching existence. He published his first story in a 1928 issue of Hugo Gernsback’s Amazing Stories, and released his final novel in 2005, just prior to his death at age 98. Already well known for early space operas such as The Legion of Space and The Legion of Time, he made the transition to the more mature Astounding style in the ‘40s with stories like The Humanoids, and later published multiple collaborations with Frederik Pohl. Along the way, he managed to begin college in the 1950s, eventually getting his Ph.D. and teaching for many years at Eastern New Mexico University. Along with his amazing science fiction resume, he managed to publish some influential fantasy during his career, and Darker Than You Think is usually considered to be one of his best novels.

Darker Than You Think, expanded to novel length in 1948, is a good example of Unknown-style fantasy, and fits into a long tradition of updating ancient fantastic traditions (in this case, werewolves and witchcraft) in order to maintain their relevance and interest for modern audiences. (Rereading Bram Stoker’s Dracula recently, I was surprised at the emphasis on science in the understanding and combating of the vampire, which must have helped update the old legends for a late nineteenth-century readership.) As in The Book of Ptath, there is a science fictional explanation for Williamson’s story of a race of magical beings threatening humanity. Usually remembered as a story about werewolves, the supernatural creatures of Darker Than You Think also encompass witches, vampires, were-beasts of all forms, and psychics. The basic conceit is that all these supernatural manifestations, as well as all the stories of monsters and gods throughout all human mythologies (including the snake in the Garden of Eden!), can be traced back to the existence of Homo lycanthropus, an offshoot of the genus Homo which competed for dominance with other pre-human species. Think of it as an evolutionary alternate history.

Darker Than You Think, expanded to novel length in 1948, is a good example of Unknown-style fantasy, and fits into a long tradition of updating ancient fantastic traditions (in this case, werewolves and witchcraft) in order to maintain their relevance and interest for modern audiences. (Rereading Bram Stoker’s Dracula recently, I was surprised at the emphasis on science in the understanding and combating of the vampire, which must have helped update the old legends for a late nineteenth-century readership.) As in The Book of Ptath, there is a science fictional explanation for Williamson’s story of a race of magical beings threatening humanity. Usually remembered as a story about werewolves, the supernatural creatures of Darker Than You Think also encompass witches, vampires, were-beasts of all forms, and psychics. The basic conceit is that all these supernatural manifestations, as well as all the stories of monsters and gods throughout all human mythologies (including the snake in the Garden of Eden!), can be traced back to the existence of Homo lycanthropus, an offshoot of the genus Homo which competed for dominance with other pre-human species. Think of it as an evolutionary alternate history.

They “sprang from another kindred type of Hominidae who were trapped by the glaciers [during the Ice Age] in the higher country … toward Tibet… They had to adapt, or die. They responded, over the slow millennia, by evolving new powers of the mind… [They] learned to leave their bodies hibernating in their caves while they went out across the ice fields—as wolves or bears or tigers—to hunt human game… In a few thousand years, their dreadful powers had overcome every other species of the genus Homo.”

Being predators, the lycanthropes allowed a larger pre-human population to live on for use as slaves and food. “They had learned to like the taste of human blood, and they couldn’t exist without it.” But around a hundred thousand years ago Homo sapiens arose, and began fighting back, discovering that silver weapons and domesticated dogs could help them in the war against Homo lycanthropus, eventually prevailing in that “strange war.” But before being wiped out entirely, these predatory creatures managed to interbreed with Homo sapiens, so that most modern humans have some trace of that genetic heritage, thus providing a scientific explanation, based on evolution and genetics, for all sorts of superhuman manifestations and witch hunts, not to mention individual psychological conflicts—“that alien inheritance haunts our unconscious minds with the dark conflicts and intolerable urges that Freud discovered and tried to explain.” Mental illness is thus presented as a result of this pre-human war still being waged in our genes! (For more on how this aspect of the novel might be related to Williamson’s own experience with psychotherapy, see Charles Dee Mitchell’s excellent WWEnd review of the novel.)

And how do these genetically-determined powers work? Well… it turns out that the mind is “an energy complex… created by the vibrating atoms and electrons of the body, and yet controlling their vibrations through the linkage of atomic probability…” Homo lycanthropus developed the power to enter a “free state,” in which this energy complex, which might be the “soul,” can disengage from the physical body. “We simply separate that living web from the body, and use the probability link to attach it to other atoms, wherever we please—the atoms of the air are easiest to control… Light can destroy or damage that mental web,” so the free state can only be entered at night. “No common matter is any real barrier to us in the free state… Our mind webs can grasp the vibrating atoms and slip through them, nearly as easily as through the air… Silver is the deadly exception—as our enemies know.” This pseudoscientific exposition is part of protagonist Will Barbee’s initiation into the ways of these witches and shape shifters. As dialogue, it’s not at all convincing, but the explanations presented in such “info dumps” are surprisingly consistent logically.

And how do these genetically-determined powers work? Well… it turns out that the mind is “an energy complex… created by the vibrating atoms and electrons of the body, and yet controlling their vibrations through the linkage of atomic probability…” Homo lycanthropus developed the power to enter a “free state,” in which this energy complex, which might be the “soul,” can disengage from the physical body. “We simply separate that living web from the body, and use the probability link to attach it to other atoms, wherever we please—the atoms of the air are easiest to control… Light can destroy or damage that mental web,” so the free state can only be entered at night. “No common matter is any real barrier to us in the free state… Our mind webs can grasp the vibrating atoms and slip through them, nearly as easily as through the air… Silver is the deadly exception—as our enemies know.” This pseudoscientific exposition is part of protagonist Will Barbee’s initiation into the ways of these witches and shape shifters. As dialogue, it’s not at all convincing, but the explanations presented in such “info dumps” are surprisingly consistent logically.

The alcoholic Barbee has never felt settled in his life, and it quickly becomes clear that his psychological issues are related to his own genetic heritage. His infatuation with the beautiful April Bell sets him on a path that will force him to choose between humanity and the exhilaration of the “free state” he has begun to experience in what he assumes to be his dreams. Like Dracula’s Von Helsing, a team of scientists has discovered the truth about the lycanthropes. These men were once Barbee’s colleagues, and he still considers them his friends, thus ratcheting up his mental conflict as it comes to be mirrored by the actual conflict between the scientists and the ancient race. The lycanthropes are determined to stop these men by any means necessary, while continuing the long game of regaining their ascendancy over humanity—a game that is nearing fruition, as they await the appearance of the their born leader, the “child of night.” By the end of the story, we know the culmination of their plans.

Interesting and entertaining as it is, Darker Than You Think does not entirely hold up. Its length could be trimmed. (I don’t have access to the original novella, but Cawthorn and Moorcock, in their guide to the best fantasy books, argue that the shorter version is superior, and they list it chronologically as belonging to 1940 rather than 1948.) As a writer, Williamson had matured from his pulp beginnings, but some “pulpishness” remains, as evidenced by the sort of dialogue quoted above, and a tendency toward the repetitive use of certain descriptive terms (e.g., Barbee seems to “shudder” an awful lot). Barbee’s character is also problematic. Using a confused and divided (literally!) point of view character is an intriguing idea, but Barbee’s continual vacillation and inability to understand what is happening to him despite overwhelming evidence, while potentially plausible given his mental state, is nonetheless annoying in a protagonist. But if you can accept the writing deficiencies (which anyone for a fondness for the pulps will easily be able to do), the rewards come when Williamson describes the freedom and power of the transformation:

Interesting and entertaining as it is, Darker Than You Think does not entirely hold up. Its length could be trimmed. (I don’t have access to the original novella, but Cawthorn and Moorcock, in their guide to the best fantasy books, argue that the shorter version is superior, and they list it chronologically as belonging to 1940 rather than 1948.) As a writer, Williamson had matured from his pulp beginnings, but some “pulpishness” remains, as evidenced by the sort of dialogue quoted above, and a tendency toward the repetitive use of certain descriptive terms (e.g., Barbee seems to “shudder” an awful lot). Barbee’s character is also problematic. Using a confused and divided (literally!) point of view character is an intriguing idea, but Barbee’s continual vacillation and inability to understand what is happening to him despite overwhelming evidence, while potentially plausible given his mental state, is nonetheless annoying in a protagonist. But if you can accept the writing deficiencies (which anyone for a fondness for the pulps will easily be able to do), the rewards come when Williamson describes the freedom and power of the transformation:

“Even by the colorless light of the stars, Barbee could see everything distinctly—every rock and bush beside the road, every shining wire strung on the striding telephone poles. ‘Faster, Will!’ April’s smooth legs clung to his racing body. She leaned forward, her breasts against his striped coat, her loose red hair flying in the wind, calling eagerly into his flattened ear… He stretched out his stride, rejoicing in his boundless power. He exulted in the clean chill of the air, the fresh odors of earth and life that passed his nostrils, and the warm burden of the girl. This was life. April Bell had awakened him out of a cold, walking death. Remembering that frail and ugly husk he had left sleeping in his room, he shuddered as he ran. ‘Faster!’ urged the girl. The dark plain and the first foothills beyond flowed back around them like a drifting cloud.”

Werewolf legends have been traced back as far as the eleventh century. Their enduring appeal has been attributed to the transgressive desire to escape the constraints of civilization and unleash primitive animalistic desires. Jack Williamson’s story of ancient racial conflict raises another possibility: Given the choice, who wouldn’t prefer to be predator rather than prey?

Next: Gothic novels of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

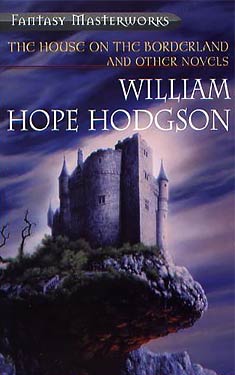

Forays into Fantasy: The House on the Borderland by William Hope Hodgson

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State College in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. Recently, he began branching out into fantasy, and was surprised by the diversity of the genre. It’s not all wizards, elves, and dragons! Scott’s new blog series, Forays into Fantasy, is an SF fan’s exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, building up an understanding of the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

The House on the Borderland (1908), by William Hope Hodgson, is an early and influential example of the strand of the fantastic known as weird fiction, most famously exemplified by the stories published in Weird Tales magazine from 1923 to 1954, by writers such as H. P. Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith, Robert Bloch, and Fritz Leiber. (The magazine has been revived several times since, and is about to be relaunched yet again under new ownership.) I’ve been making my way slowly through Ann and Jeff VanderMeer’s massive new anthology, The Weird: A Compendium of Dark and Strange Stories, which is highly recommended for anyone looking for an entry into this branch of fantasy. It traces the development of the subgenre over the last century, the earliest examples having begun appearing at about the same time as Hodgson’s novel, which is mentioned in the introduction as a key early progenitor of the weird tale. Recently, China Miéville, M. John Harrison, and other like-minded writers have promoted what they call the “New Weird,” as a modern incarnation of the form.

The House on the Borderland (1908), by William Hope Hodgson, is an early and influential example of the strand of the fantastic known as weird fiction, most famously exemplified by the stories published in Weird Tales magazine from 1923 to 1954, by writers such as H. P. Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith, Robert Bloch, and Fritz Leiber. (The magazine has been revived several times since, and is about to be relaunched yet again under new ownership.) I’ve been making my way slowly through Ann and Jeff VanderMeer’s massive new anthology, The Weird: A Compendium of Dark and Strange Stories, which is highly recommended for anyone looking for an entry into this branch of fantasy. It traces the development of the subgenre over the last century, the earliest examples having begun appearing at about the same time as Hodgson’s novel, which is mentioned in the introduction as a key early progenitor of the weird tale. Recently, China Miéville, M. John Harrison, and other like-minded writers have promoted what they call the “New Weird,” as a modern incarnation of the form.

Both the VanderMeers and Michael Moorcock, in his “Foreweird” to the same book, avoid providing a precise definition of weird fiction, making the point that this slipperiness is part of its appeal. According to Moorcock: “In popular terms, it came to mean a supernatural story in something of the Gothic tradition… We’re [now] clearly comfortable with a term covering pretty much anything from absurdism to horror, even occasionally social realism.” While deriving somewhat from the Gothic tradition (more on that in a future post), the VanderMeers point out that Lovecraft himself defined the weird tale as “a story that does not fall into the category of traditional ghost story or Gothic tale” of the 1800s. “Instead, it represents the pursuit of some indefinable and perhaps maddeningly unreachable understanding of the world beyond the mundane… through fiction that comes from the more unsettling, shadowy side of the fantastic tradition.” To my mind, stories in the weird fiction tradition evoke the uncanny.

It’s difficult to define, but once you’ve experienced it, you’ll know it when you read it. Most aficionados seem to agree that William Hope Hodgson’s The House on the Borderland is a good place to start. Lovecraft and Miéville, among many others, have lauded Hodgson’s work, and this short novel is a clear precursor to the even more influential Lovecraft. As in much of Lovecraft, the story is centered on the idea that there is an unseen world that threatens to leak into our reality. The nature of this foreign dimension and its denizens is never really understood. It seems to represent a threat, but is also a source of wonder. It occurs to me that the introduction of this type of story into literature early in the twentieth century is a response to a growing feeling at the time that the old certainties were giving way, change was accelerating, and the world was becoming ever more chaotic and incomprehensible, and indifferent. The continuing appeal of this branch of the fantastic could testify to the fact that this feeling has certainly not gone away.

The novel begins in 1877. Two men on a fishing vacation in western Ireland come across the ruins of a large house next to a water-filled pit in a now wild but once-cultivated grove in an otherwise barren landscape. They take away a musty manuscript found in the ruins and, unable to shake off a feeling of dread and danger that seems to arise from the grove, do not return. The vacationers’ discovery of the manuscript in the first chapter, and their investigation in the final chapter into the reliability of what they’ve read, frame our reading of the first-person manuscript, which makes up most of the novel. The framing chapters provide evidence that seems to verify at least some aspects of the narrative, written by the final owner of the house, which might otherwise be dismissed as dream or hallucination. (The framing device is similar to that in Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw — another first person account of the supernatural — but in this case, the framing narrators clearly come to be convinced by the account they are reading.)

The novel begins in 1877. Two men on a fishing vacation in western Ireland come across the ruins of a large house next to a water-filled pit in a now wild but once-cultivated grove in an otherwise barren landscape. They take away a musty manuscript found in the ruins and, unable to shake off a feeling of dread and danger that seems to arise from the grove, do not return. The vacationers’ discovery of the manuscript in the first chapter, and their investigation in the final chapter into the reliability of what they’ve read, frame our reading of the first-person manuscript, which makes up most of the novel. The framing chapters provide evidence that seems to verify at least some aspects of the narrative, written by the final owner of the house, which might otherwise be dismissed as dream or hallucination. (The framing device is similar to that in Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw — another first person account of the supernatural — but in this case, the framing narrators clearly come to be convinced by the account they are reading.)

The manuscript’s unnamed narrator, referred to by Hodgson (in the guise of the manuscript’s editor) as The Recluse, has bought the property, knowing its evil reputation, as a refuge from the world which, we eventually learn, he has abandoned out of grief over the death of a lover.