Forays into Fantasy: The Dying Earth by Jack Vance

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State College in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. Recently, he began branching out into fantasy, and was surprised by the diversity of the genre. It’s not all wizards, elves, and dragons! Scott’s new blog series, Forays into Fantasy, is an SF fan’s exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, building up an understanding of the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

Jack Vance creates a subgenre: The Dying Earth

Jack Vance creates a subgenre: The Dying Earth

The work of Grand Master Jack Vance can be segmented into science fiction and fantasy (actually, he wrote some mysteries, too), but they all straddle the borderline between the two genres. Both his fantasy, beginning with The Dying Earth (1950), and his science fiction, beginning with Big Planet (1952), can be seen as the earliest of the modern “planetary romances” – stories set on alien worlds, with plots involving exploration of the sociological and anthropological aspects of these worlds. An important precursor is Clark Ashton Smith, whose tales were often set in far future settings where “technology is indistinguishable from magic,” to borrow Arthur C. Clarke‘s maxim. Leigh Brackett‘s stories of Mars and Venus, in turn influenced by Edgar Rice Burroughs, are also important early examples. These stories are not hard science fiction – the nature of the technology is not a focus of the stories, and there are no technological problems to understand or solve. But they are not pure fantasy either, since they are set on alien worlds or in the far future of Earth, and may include the trappings of SF such as spaceships and aliens.

Forays into Fantasy: The Compleat Enchanter by L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State College in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. Recently, he began branching out into fantasy, and was surprised by the diversity of the genre. It’s not all wizards, elves, and dragons! Scott’s new blog series, Forays into Fantasy, is an SF fan’s exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, building up an understanding of the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

In 1939, L. Sprague de Camp, just embarking on a writing career, was introduced to Fletcher Pratt, who had published a number of stories in the science fiction pulps beginning in 1928, while working for Hugo Gernsback as a translator of European SF stories. De Camp became a regular at Pratt’s gatherings based around his elaborate naval war games. When John W. Campbell‘s Unknown fantasy magazine debuted in 1939, Pratt suggested a collaboration between the two authors–a series of novellas "about a hero who projects himself into the parallel worlds described in our world in myths and legends. We made our protagonist a brash, self-conceited young psychologist named Harold Shea," as de Camp explains in his 1975 essay "Fletcher and I."

In 1939, L. Sprague de Camp, just embarking on a writing career, was introduced to Fletcher Pratt, who had published a number of stories in the science fiction pulps beginning in 1928, while working for Hugo Gernsback as a translator of European SF stories. De Camp became a regular at Pratt’s gatherings based around his elaborate naval war games. When John W. Campbell‘s Unknown fantasy magazine debuted in 1939, Pratt suggested a collaboration between the two authors–a series of novellas "about a hero who projects himself into the parallel worlds described in our world in myths and legends. We made our protagonist a brash, self-conceited young psychologist named Harold Shea," as de Camp explains in his 1975 essay "Fletcher and I."

De Camp credits Pratt with the original idea behind the series, and considers him the "senior member" of the collaboration. They brainstormed the plots together, with Pratt providing most of the background for the stories’ mythological and literary settings. De Camp would take notes, and then write a rough draft, which Pratt would turn into a final draft. Lastly, de Camp would make the final edits prior to sending them to Campbell. The stories were a perfect fit for Unknown, where the first three novellas were published in 1940 and 1941. As John Clute and John Grant explain in The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Campbell sought to ensure the fantasy elements in Unknown obeyed some set of laws, in effect treating the supernatural as another science."

The title of the second novella, "The Mathematics of Magic" (1940), nicely encapsulates the rationalized approach to fantasy Campbell was looking for in the magazine. In each story, a mental technique developed by a group of psychologists is used to transport Shea and his companions to an alternate universe based on a national mythology or well-known literary setting. As lead psychologist Dr. Chalmers puts it, "the method consists of filling your mind with the fundamental assumptions of the world in question…. If one of these infinite other worlds–which up to now may be said to exist in a logical but not in an empirical sense–is governed by magic, you might expect to find a principle like that of dependence invalid, but principles of magic, such as the Law of Similarity, valid." Our world, in which cause and effect are linked by physical laws (dependence), is then replaced by a world where "effects resemble causes. It’s not valid for us, but primitive peoples firmly believe it. For instance, they think you can make it rain by pouring water on the ground with appropriate mumbo jumbo." By internalizing these magical laws, our heroes not only transport themselves to alternate worlds, but, once achieving a thorough enough understanding of the laws of these worlds, become practicing magicians there.

The title of the second novella, "The Mathematics of Magic" (1940), nicely encapsulates the rationalized approach to fantasy Campbell was looking for in the magazine. In each story, a mental technique developed by a group of psychologists is used to transport Shea and his companions to an alternate universe based on a national mythology or well-known literary setting. As lead psychologist Dr. Chalmers puts it, "the method consists of filling your mind with the fundamental assumptions of the world in question…. If one of these infinite other worlds–which up to now may be said to exist in a logical but not in an empirical sense–is governed by magic, you might expect to find a principle like that of dependence invalid, but principles of magic, such as the Law of Similarity, valid." Our world, in which cause and effect are linked by physical laws (dependence), is then replaced by a world where "effects resemble causes. It’s not valid for us, but primitive peoples firmly believe it. For instance, they think you can make it rain by pouring water on the ground with appropriate mumbo jumbo." By internalizing these magical laws, our heroes not only transport themselves to alternate worlds, but, once achieving a thorough enough understanding of the laws of these worlds, become practicing magicians there.

In the first novella, "The Roaring Trumpet" (1940), Shea, feeling vaguely dissatisfied with his humdrum life in Ohio and yearning for adventure, fires up the "syllogismobile" (his irreverent term for the logical formulations used for inter-universe transportation) for a trip to the world of Irish legend. But Shea has not grasped Dr. Chalmers concepts quite well enough to control the process precisely, and ends up in the wrong legend–that of Norse mythology. Shea is also unprepared for how to make use of magic in this world, but he gradually figures it out, becoming more proficient as he learns how the laws work. This partial understanding of the rules of the worlds he and his companions travel to means that the magic often doesn’t go quite right–the main source of the humor for which the series is known. In "The Mathematics of Magic", Shea and Chalmers, trying to conjure a dragon, get the qualitative aspect of the spell correct, but can’t nail down the quantitative. Instead of one dragon, they get 100; on the second attempt, they get .01 (a mini-dragon). They can’t figure out how to get the decimal point in the right place.

In the first novella, "The Roaring Trumpet" (1940), Shea, feeling vaguely dissatisfied with his humdrum life in Ohio and yearning for adventure, fires up the "syllogismobile" (his irreverent term for the logical formulations used for inter-universe transportation) for a trip to the world of Irish legend. But Shea has not grasped Dr. Chalmers concepts quite well enough to control the process precisely, and ends up in the wrong legend–that of Norse mythology. Shea is also unprepared for how to make use of magic in this world, but he gradually figures it out, becoming more proficient as he learns how the laws work. This partial understanding of the rules of the worlds he and his companions travel to means that the magic often doesn’t go quite right–the main source of the humor for which the series is known. In "The Mathematics of Magic", Shea and Chalmers, trying to conjure a dragon, get the qualitative aspect of the spell correct, but can’t nail down the quantitative. Instead of one dragon, they get 100; on the second attempt, they get .01 (a mini-dragon). They can’t figure out how to get the decimal point in the right place.

In another example, at the end of "The Roaring Trumpet," Shea comes up with a spell to get Heimdall and himself to Ragnarok on time by riding flying broomsticks, but the spell is not precise enough to include a reliable means of controlling their flight:

"Shea gripped the stick till his knuckles were white. Up – up – up he went, till everything was blotted out in the damp opaqueness of cloud. The broom rushed on at a steeper and steeper angle, till Shea found to his horror that it was rearing over backward. He wound his legs around the stick and clung, while the broom hung for a second suspended at the top of its loop with Shea dangling beneath. It dived, then fell over sidewise, spun this way and that, with its passenger flopping like a bell clapper."

These misapplied spells, used for comedic effect, are a hallmark of the stories, and a source of the title of the book that combines the first two novellas, and by which the series itself has come to be known–The Incomplete Enchanter (1941). As for the plot, after becoming magically proficient and helping the Norse gods in the run-up to Ragnarok, Shea is sent home by a witch prior to the world-ending battle. Making better preparations this time, Shea and Chalmers, in "The Mathematics of Magic," travel to the world of Spenser’s The Faerie Queen (1596). While helping Queen Gloriana defeat a cabal of evil magicians (ending with a rather startling scene of magical massacre), Shea meets the huntress Belphebe, who will become his wife and travel with him back to Ohio at story’s end, while Chalmers stays behind, having fallen for a magical doppelganger of Lady Florimel, who he hopes to transform into a real woman once he masters enough magic.

These misapplied spells, used for comedic effect, are a hallmark of the stories, and a source of the title of the book that combines the first two novellas, and by which the series itself has come to be known–The Incomplete Enchanter (1941). As for the plot, after becoming magically proficient and helping the Norse gods in the run-up to Ragnarok, Shea is sent home by a witch prior to the world-ending battle. Making better preparations this time, Shea and Chalmers, in "The Mathematics of Magic," travel to the world of Spenser’s The Faerie Queen (1596). While helping Queen Gloriana defeat a cabal of evil magicians (ending with a rather startling scene of magical massacre), Shea meets the huntress Belphebe, who will become his wife and travel with him back to Ohio at story’s end, while Chalmers stays behind, having fallen for a magical doppelganger of Lady Florimel, who he hopes to transform into a real woman once he masters enough magic.

A third story, "The Castle of Iron," appeared in Unknown in 1941, and was later expanded into a novel published in 1950. The three stories would ultimately be collected in 1975 as The Compleat Enchanter. This time, Chalmers has transported himself from the world of The Faerie Queen to the world of its literary source–Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso (1532), based on legends of the conflict between Charlemagne’s knights and the Saracens attempting to invade Europe in the eighth century–hoping to get assistance from that world’s sorcerers in restoring Florimel to humanity. In another example of "incomplete enchantment," Chalmers, attempting to snatch Shea from Ohio in order to assist his magical studies, ends up with Belphebe instead. Now in Ariosto’s world instead of Spenser’s, Belphebe becomes Belphagor, the corresponding character in Orlando Furioso, with no memory of her previous adventures or her marriage to Shea. Confined to the eponymous castle by a powerful sorcerer, Shea and his companions must master the rules of Ariosto’s magical world in order to restore Belphebe and Florimel, while avoiding getting caught in the middle of the local conflict. Their misadventures involve, among other magical madness, infantile Paladins, a mistaken werewolf, a hippogriff and a magic carpet, culminating with a storming sorcerers’ battle.

After expanding "The Castle of Iron", de Camp and Pratt went on to publish two more novellas–"The Wall of Serpents" in 1953 and "The Green Magician" in 1954. The full sequence of five eventually appeared as The Complete Compleat Enchanter. (The Fantasy Masterworks version of The Compleat Enchanter also contains all five stories. The NESFA Press collection titled The Mathematics of Magic also includes all the stories, with the addition of two more Shea stories written by de Camp in the early ‘90s.) In "The Wall of Serpents", Shea visits the world of Finnish mythology as described in the Kalevala, and finally makes it to Ireland in "The Green Magician", but the formula has become a little tiresome by that point.

After expanding "The Castle of Iron", de Camp and Pratt went on to publish two more novellas–"The Wall of Serpents" in 1953 and "The Green Magician" in 1954. The full sequence of five eventually appeared as The Complete Compleat Enchanter. (The Fantasy Masterworks version of The Compleat Enchanter also contains all five stories. The NESFA Press collection titled The Mathematics of Magic also includes all the stories, with the addition of two more Shea stories written by de Camp in the early ‘90s.) In "The Wall of Serpents", Shea visits the world of Finnish mythology as described in the Kalevala, and finally makes it to Ireland in "The Green Magician", but the formula has become a little tiresome by that point.

The basic idea is always the same–our heroes arrive in a new world where they must learn the rules of magic in order to help avert a catastrophe and find their way home. The strength of the stories is not in the plotting, but in the comedy and the excitement created by the incidents which tumble on one after another as the stories progress. The stories are also notable for their tone of near-intoxication induced in the characters and reader as a result of the pure exhilaration of their travels into the worlds of magic. (But, as with other sorts of intoxication, it can be overdone, and I was having a hard time continuing with the fourth and fifth novellas, as they began to seem repetitive. This is a series probably best experienced in smaller doses.) As in Silverlock, which also made use of Orlando Furioso as a major source (and whose author, John Myers Myers, was probably influenced by the Shea stories when writing his 1949 novel), immersion in the world of stories is a transformative and life-enhancing experience for characters who feel repressed by their mundane lives. By extension, this idea might be seen to represent the value of fantasy itself to its readers.

Along with being a key exemplar of Unknown-style fantasy, the Incomplete Enchanter sequence also fits into a long tradition of humorous fantasy, stretching back to A Midsummer Night’s Dream and forward to Terry Pratchett. Pratt and de Camp certainly would have known the work of James Branch Cabell and Thorne Smith, published earlier in the century, which mixes mythology, fantasy, and social satire. In turn, de Camp and Pratt would influence the humorous fantasies of Piers Anthony, Robert Asprin, and many others. In the 1990s, Baen would publish two anthologies of new Harold Shea stories by modern authors influenced by the series.

Along with being a key exemplar of Unknown-style fantasy, the Incomplete Enchanter sequence also fits into a long tradition of humorous fantasy, stretching back to A Midsummer Night’s Dream and forward to Terry Pratchett. Pratt and de Camp certainly would have known the work of James Branch Cabell and Thorne Smith, published earlier in the century, which mixes mythology, fantasy, and social satire. In turn, de Camp and Pratt would influence the humorous fantasies of Piers Anthony, Robert Asprin, and many others. In the 1990s, Baen would publish two anthologies of new Harold Shea stories by modern authors influenced by the series.

A major aspect of the comedy in these stories, the inability to control magic, whether as a source of comedy or suspense, also has a long history. For example, consider Goethe’s The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (1798), which became the basis for the Mickey Mouse sequence in Disney’s Fantasia (coincidentally also released in 1940, the same year the Shea sequence began). Shea’s unending procession of dragons is reminiscent of the multiplying brooms and water pails in that story. And the idea that magical spells can be difficult to control, resulting in unintended consequences, became the starting point of nearly every plot in the hundreds of episodes of Bewitched and I Dream of Jeannie. Come to think of it, in this age of CGI, The Magical Misadventures of Harold Shea would probably work pretty well as a sitcom….

GMRC Review: Deathbird Stories by Harlan Ellison

Long time WWEnd member and Uber User, Emil Jung, is an obsessive SF/F reader and as such he’s become a huge supporter of WWEnd. (We often refer to him as our "South African Bureau.") Besides hanging out here, Emil writes poetry on his blog emiljung.posterous.com. This is the fourth of Emil’s GMRC reviews to feature in our blog.

Long time WWEnd member and Uber User, Emil Jung, is an obsessive SF/F reader and as such he’s become a huge supporter of WWEnd. (We often refer to him as our "South African Bureau.") Besides hanging out here, Emil writes poetry on his blog emiljung.posterous.com. This is the fourth of Emil’s GMRC reviews to feature in our blog.

If there ever was a kind of excessive, unorthodox or hysterical posturing in SF, Harlan Ellison definitely embodies it. And not only in the choice of the titles of his impressive stories. He certainly has a flare for verbal thrift, rarely struggling to grope for effect, as Connie Willis may well atest to. Despite his outrageous actions that often include letigation of all kinds against an impressive cast of you-know-who’s, which I believe has a lot more to do with upholding a bad-boy image than anything else of substance, Ellison certainly is gifted with literary cleverness and as such is one of the most decorated writers in the genre, winning over 100 awards. He works almost exclusively within the short story form, and consequently has remained little known outside SF circles. Apart from editing the landmark Dangerous Visions anthology, and its follow-up Again, Dangerous Visions, Ellison also did some work on Star Trek, Babylon 5 and The Outer Limits, one episode of which named "Soldier" being the inspiration for The Terminator. True to form, Ellison sued.

If there ever was a kind of excessive, unorthodox or hysterical posturing in SF, Harlan Ellison definitely embodies it. And not only in the choice of the titles of his impressive stories. He certainly has a flare for verbal thrift, rarely struggling to grope for effect, as Connie Willis may well atest to. Despite his outrageous actions that often include letigation of all kinds against an impressive cast of you-know-who’s, which I believe has a lot more to do with upholding a bad-boy image than anything else of substance, Ellison certainly is gifted with literary cleverness and as such is one of the most decorated writers in the genre, winning over 100 awards. He works almost exclusively within the short story form, and consequently has remained little known outside SF circles. Apart from editing the landmark Dangerous Visions anthology, and its follow-up Again, Dangerous Visions, Ellison also did some work on Star Trek, Babylon 5 and The Outer Limits, one episode of which named "Soldier" being the inspiration for The Terminator. True to form, Ellison sued.

His best known collection is arguably The Beast That Shouted Love at the Heart of the World, which features the definitive New Wave story "A Boy And His Dog" that won the Nebula for best novella, and upsetting almost everyone, from liberals and feminists to the right wing alike, and of course, many of the Golden Age SF writers. After having read a few of Ellison’s stories, "A Boy and His Dog" remains his best, one of the few post-apocalyptic narratives to depict how raw and brutal existence after a nuclear holocaust would be – and equally successful in protesting and allegorizing the Vietnam War. Equally ingenious is Deathbird Stories, a collection probably closest to the horror genre, with an odd few elements of science fiction and fantasy thrown in.

As the subtitle, A Pantheon of Modern Gods, suggests, the theme is gods, and in particular the "new" gods (or devils) of our modern society. These are: the god of speed, the god of beauty, the god of money, the god of mechanical and technoligcal wonders, the god of apocryphal dreams and the gods of pollution. Even the god of the guilty, if there could be such a thing, albeit a Freudian trope. The stories are tied together by the concept that gods are real only as long as they have people who believe in them. We find echoes of this in Neil Gaiman’s phenominal American Gods. Ellison writes in the introduction:

"When belief in a god dies, the god dies… to be replaced by newer, more relevant gods."

It’s not a far-fetched assumption. Afterall, Thor and Odin disappeared when the Vikings took up the cross and Apollo was reduced to rubble along with his temples. Ellison offers a litany of dead gods. These 19 stories are essentially about the merits of religion and the religious and true to form, Ellison crushes eggshells in his usual confrontational manner, with a caveat lector at the beginning that warns the reader against reading the entire collection in one sitting because of the "emotional content:"

"It is suggested that the reader not attempt to read this book at one sitting. The emotional content of these stories, taken without break, may be extremely upsetting. This note is intended most sincerely, and not as hyperbole."

Despite there being an element of humor in some of these stories, the warning should not be taken lightly. It is not the usual Ellison arrogance at play here – they did exhaust and deaden my spirit. Still, Ellison’s missive does drive home the point that mankind is drifitng away from the belief in a benevolent, all-knowing, all-loving God and is instead transferring its faith to soulless pursuits and material possessions. There are truths present here, and some of them are very uncomfortable, taking the shape of monstrous, twisted forms, old creatures of myth like basilisks, gargoyles, minotaurs and even dragons, allegories for the new gods of gambling, the modern metropolis, pollution, sex, automobile showrooms and many other depraving endeavors. The gods appear to be a remarkably fragile lot.

These are my favorite stories from the collection:

"Pretty Maggie Moneyeyes" is about the god of the slot machine and the subsequent dead-end that Las Vegas could be. A similar kind of worship is found in "Neon," about a guy who seeks carnal knowledge with neon lights.

"Along the Scenic Route" is a narrative about a freeway autoduel of the future, very prescient to our modern day road-rage fueled obsessions on the world’s freeways.

"Basilisk" perspicaciously combines the Greek myth of a serpent-like creature with a lethal gaze and Mars, the hungry God of War. Lance Corporal Vernon Lestig does terrible things but I understood, and may even have sympathised with his reasons.

"On the Downhill Side" is just a beautiful and touching story about two ghosts who meet on a street in New Orleans. The God of Love allows them one more chance to find love in each other’s arms. The man had loved too much, leading to multiple divorces and his ultimate suicide, and the woman had remained a virgin until her early death. There is a dire price to be paid, a sacrificial compromise "forming one spirit that would neither love too much, nor too little." I could not help feeling that this is probably how Ellison truly sees love and religion operating. An emotionally engaging story, perfectly paced – I simply loved it.

"Shattered Like a Glass Goblin" invokes the paranoid fears brought about by hallucinogenic drugs within the surreal atmosphere of a hippie retreat. I find this story a magnificent allegory on the all-consuming downward spiral of drug addiction, culminating in a final hallucination as deciphered symbol of the inevitable surrender of the main protagonist, who thinks he is a glass sculpture of a goblin and his girlfriend a werewolf. When he tries to talk to her for one final time, she attacks him and he shatters into a thousand pieces.

"Paingod," which is my clear favorite in the entire collection, is about Trente the Paingod, who delivers pain and suffering when and if necessary to each conscious being across all the universes, and decided one day to find out first-hand what pain feels like from a sculptor who has lost his ability to sculp. The harrowing conclusion that pain is a blessing because without it there can be no joy still reverberates strongly with me.

The three weakest stories for me are:

"Rock God" is a rather pedestrian affair, dated, with the frantic corruptness of the protagonist very stereotypical.

"At the Mouse Circus" which I can’t say anything meaningful except that it features the king of Tibet and a cadillac and that I have no idea what Ellison is trying to convey.

"The Place With No Name" has Prometheus in it, but much like the movie, disappoints with things I did not understand at all and other things that were only too clear. There is this somewhat shocking denouement: what if Jesus and Prometheus had been lovers, were aliens that felt strong and loving empathy toward earthlings and gave them gifts, only to be punished (and crucified) by the other gods for doing so?

A polarizing collection with this many narratives dealing more or less with the same subject matter is bound to have a few unappealing stories. Nonetheless, there are still other, brilliant and well crafted stories like the catchy "Adrift Just Off the Islets of Langerhans: Lattitude 38° 54′ N, Longitude 77° 00′ 13" W" and the story the title is taken from, "Deathbird." I’m certain everyone who reads this collection will discover their own favorites. Take note of the caveat lector, though and read these divergent stories cautiously over a stretched period of time. They are hugely rewarding, even if exhausting. Ellision has always been a polemic figure who has never been afraid to articulate and share his opinions. This is true even of his writing. It is a difficult read, even painful at times, but as Ellison so expressly pointed out: what is joy without a little pain?

A polarizing collection with this many narratives dealing more or less with the same subject matter is bound to have a few unappealing stories. Nonetheless, there are still other, brilliant and well crafted stories like the catchy "Adrift Just Off the Islets of Langerhans: Lattitude 38° 54′ N, Longitude 77° 00′ 13" W" and the story the title is taken from, "Deathbird." I’m certain everyone who reads this collection will discover their own favorites. Take note of the caveat lector, though and read these divergent stories cautiously over a stretched period of time. They are hugely rewarding, even if exhausting. Ellision has always been a polemic figure who has never been afraid to articulate and share his opinions. This is true even of his writing. It is a difficult read, even painful at times, but as Ellison so expressly pointed out: what is joy without a little pain?

GMRC Review: Lavinia by Ursula K. Le Guin

Glenn Hough (gallyangel) is, among other things, a nonpracticing futurist, an anime and manga otaku, a gourmet, a writer of science fiction novels which don’t get published to world wide acclaim, and is almost obsessive about finishing several of the lists tracked on WWEnd. This is Glenn’s first featured review for the GMRC.

Glenn Hough (gallyangel) is, among other things, a nonpracticing futurist, an anime and manga otaku, a gourmet, a writer of science fiction novels which don’t get published to world wide acclaim, and is almost obsessive about finishing several of the lists tracked on WWEnd. This is Glenn’s first featured review for the GMRC.

This is a tale of a footnote. Much like Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, which looks up at the wide world of Hamlet from the POV of minor characters, Lavinia immerses us in the world of Vergil’s Aeneid from the POV of a woman even further removed from the central action. In the Aeneid, Lavinia is named, she plays a role, a war is fought over her marriage rites since she was being used as a political tool, but yet, she never speaks a word in the poem.

Vergil renders her mute.

Le Guin has now given her a voice.

In terms of presentation, Le Guin’s Lavinia occupies middle ground. It is not the epic ground of heroes and jealous gods that is the backbone of Vergil’s Aeneid. The gods in Lavinia have lost their mythic stature. They are now gods of woods, auguries, the hearth, the storehouse. Gods that are a backbone of life but not humanized master movers. Nor is this book a realist exploration of barbaric bronze age peoples, based in what little archaeology, anthropology and the stories, myths, and lies which is all the historians have of the age. Middle ground. Barbarous yes, but gentled. Epic heroes, not quite, but these are the root cultures which founded Rome. And the seeds of that coming glory are present.

As the novel opens and we are drawn into this culture, we quickly see the parallels between two well known Greek ladies: Helen and Cassandra. Like Helen, a war is found over her. Helen gave of herself, Lavinia withheld herself. Like Cassandra, Lavinia had foresight. But instead of speaking and not being believed, Lavinia keeps the knowledge to herself. Lavinia has to act this way since the poet gave her no lines in his poem. For in vision quests performed at a sacred sulfur spring, Lavinia meets the dying Vergil. He is a shade, a shadow, filled with grief over his poem which is unfinished and incomplete. He morns his lack of attention concerning Lavinia. It is from Vergil that Lavinia learns her future, the long litany of deaths which are committed in her name, and the knowledge of a son which is a sire to kings, which lead to the greatness of Rome.

As the novel opens and we are drawn into this culture, we quickly see the parallels between two well known Greek ladies: Helen and Cassandra. Like Helen, a war is found over her. Helen gave of herself, Lavinia withheld herself. Like Cassandra, Lavinia had foresight. But instead of speaking and not being believed, Lavinia keeps the knowledge to herself. Lavinia has to act this way since the poet gave her no lines in his poem. For in vision quests performed at a sacred sulfur spring, Lavinia meets the dying Vergil. He is a shade, a shadow, filled with grief over his poem which is unfinished and incomplete. He morns his lack of attention concerning Lavinia. It is from Vergil that Lavinia learns her future, the long litany of deaths which are committed in her name, and the knowledge of a son which is a sire to kings, which lead to the greatness of Rome.

To me, Lavinia’s relationship to the poet Vergil and her knowledge that she is a character in his poem is the most interesting aspect of the book. Lavinia is bound by the limitations Vergil gives her, but fills that space with life, her life; the life of a daughter of a king, wife to the exiled Trojan Aeneas, who has taken up kingship in what will become Italy, mother and grandmother to kings. She is a queen. Since Vergil gave her no lines, little life and no death, in the end Lavinia too does not die. Her body passes but Lavinia lingers in the quiet places of her country. Her immortality is forever linked to the written word of the poet. While Vergil’s words live, Lavinia lives. While Le Guin’s words live, Lavinia lives.

Highly recommended.

Three New Book Lists!

I love a good list. From Letterman’s latest Top Ten to IMDb’s Top 250 Movies to the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted I can’t get enough of them. Especially book lists! They fascinate and infuriate in equal parts and provide endless points for discussion and contention among fans. Especially when the list purports to be the "best of" something or other.

Genre fiction is replete with "best of" lists and based on your response to the 20 SF/F/H Lists we have here on WWEnd it seems you folks can’t get enough of ’em either. No sooner do we post a new one than we start getting calls for another! I love it. There are so many out there I doubt we’ll ever run out of new ones and since each list offers a different take on what’s best we’re perfectly happy to keep adding more.

We’ve added some new ones recently–including one just yesterday–that you guys asked for specifically and we wanted to let you know they’re up. Enjoy!

Damien Broderick and Paul Di Filippo’s book list, from their new book Science Fiction: The 101 Best Novels 1985–2010, is a continuation of David Pringle’s Science Fiction: The 100 Best Novels. Pringle passes the torch in a foreword to the new volume: "Having been unable to keep up with all those new SF works myself, I am delighted that Damien Broderick and Paul Di Filippo have taken it upon themselves to do the job, and I am very happy to endorse their excellent book."

Damien Broderick and Paul Di Filippo’s book list, from their new book Science Fiction: The 101 Best Novels 1985–2010, is a continuation of David Pringle’s Science Fiction: The 100 Best Novels. Pringle passes the torch in a foreword to the new volume: "Having been unable to keep up with all those new SF works myself, I am delighted that Damien Broderick and Paul Di Filippo have taken it upon themselves to do the job, and I am very happy to endorse their excellent book."

David Pringle has written several guides to science fiction and fantasy. His famous book, Science Fiction: The 100 Best Novels, is a highly regarded primer for the genre. In 1988 Pringle followed up with his Modern Fantasy: The 100 Best Novels (1946-1987). Primarily the book comprises 100 short essays on the selected works, covered in order of publication, without any ranking. It is considered an important critical summary of the field of modern fantasy literature.

David Pringle has written several guides to science fiction and fantasy. His famous book, Science Fiction: The 100 Best Novels, is a highly regarded primer for the genre. In 1988 Pringle followed up with his Modern Fantasy: The 100 Best Novels (1946-1987). Primarily the book comprises 100 short essays on the selected works, covered in order of publication, without any ranking. It is considered an important critical summary of the field of modern fantasy literature.

Worlds Without End has over 800 reviews of some of the best books in science fiction, fantasy and horror. These reviews have been submitted by our members and range from simple opinions ("This book sucked!") to well reasoned technical reviews of some of your favorite genre books. We’ve created this list so you can find all the reviewed books in one place and, if you’re a logged in WWEnd member, you can use BookTrackr™ to easily find reviews for any of the books you’ve read.

Worlds Without End has over 800 reviews of some of the best books in science fiction, fantasy and horror. These reviews have been submitted by our members and range from simple opinions ("This book sucked!") to well reasoned technical reviews of some of your favorite genre books. We’ve created this list so you can find all the reviewed books in one place and, if you’re a logged in WWEnd member, you can use BookTrackr™ to easily find reviews for any of the books you’ve read.

Outside the Norm: Dubravka Ugresic’s Baba Yaga Laid an Egg

Rhonda Knight is an Associate Professor of English at Coker College in Hartsville, SC. She teaches Medieval and Renaissance literature as well as composition courses. When she looked over last year’s reading list, she was shocked to see that only 17% of the authors she read were women. This blog will record her attempts to read authors that are generally considered out of the science fiction norm: women, persons of color, and non-U.S. and non-U.K. authors.

I began this Outside the Norm blog because I wanted to challenge myself to read more books by women, persons of color and nationalities other than American and British. So far I’ve read canonical authors like Le Guin and those who are starting to make a name in the F and SF world like Nnedi Okorafor. I’m also beginning to see this title as a license to write about others whose speculative work is just outside the parameters of the lists and awards compiled here. This blog is about one of those books, Dubravka Ugresic‘s Baba Yaga Laid an Egg.

This book first came to my attention because it won the 2010 James Tiptree, Jr. Award. The Tiptree’s mission, as stated on its website, is to honor a science fiction or fantasy work "that expands or explores our understanding of gender" and is given each year at WisCon. Ugresic is a Croatian academic who was forced into exile by a nationalist government. Most of her books and collections of essays are political in nature. This book was nominated for the Man Booker International Prize, so, as you can see, she’s not an author whose name would typically end up on a list of the year’s best fantasy writers. Yet, her use of myth in this book placed the book in the realm of fantasy for some readers like the Tiptree jury. The book is a three-part engagement with Baba Yaga, the witch-like character of Slavic folklore.

I confess that all I really knew about Baba Yaga came through an introduction via the prog rock CD Pictures at an Exhibition (1972) by Emerson, Lake and Palmer. That group had recorded a suite by the Russian composer, Modest Mussorgsky, which Mussorgsky had based on an art exhibition by the Russian artist Viktor Hartmann. (For more about Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, check out the music and new images here.) One of the images that inspired subsequent songs by Mussorgsky and Emerson, Lake, and Palmer was "The Hut of Baba Yaga." This song sent my younger self off to research Baba Yaga.  I learned that Baba Yaga lived in a giant hut that walked around on huge chicken legs. Much like the witches in Grimm’s fairy tales, she lured children to her forest hut and ate them. She flew around in a mortar, using the pestle like an oar, and used a broom to sweep away her tracks. Here you can see her connection to the more western witches on broomsticks. However, no previous knowledge of Baba Yaga is required to read this book because the reader is slowly educated through the author’s three sections. This structure and strategy is what makes this book so interesting and made me decide to write this review.

I learned that Baba Yaga lived in a giant hut that walked around on huge chicken legs. Much like the witches in Grimm’s fairy tales, she lured children to her forest hut and ate them. She flew around in a mortar, using the pestle like an oar, and used a broom to sweep away her tracks. Here you can see her connection to the more western witches on broomsticks. However, no previous knowledge of Baba Yaga is required to read this book because the reader is slowly educated through the author’s three sections. This structure and strategy is what makes this book so interesting and made me decide to write this review.

The short prologue "At First You Don’t See Them…" unapologetically tells the reader that this book will be about old women:

Sweet little old ladies. At first you don’t see them. And then, there they are, on the tram, at the post office, in the shop, at the doctor’s surgery, on the street, there is one, there is another, there is a fourth over there, a fifth, a sixth, how could there be so many of them all at once? (2)

The invisibility of these "little old ladies" is a direct comment on society’s tendency to dismiss the elderly and their needs and forget about their continued usefulness to society. Ugresic’s book goes beyond this generalization of invisibility and takes on the ways that our view of "little old ladies" is often based on gender stereotypes created by earlier patriarchal societies, especially crone figures like the Baba Yaga.

The first section "Go There – I Know Not Where – and Bring Me Back a Thing I Lack" has no speculative fiction elements. It is written in the first person. The narrator is a famous author who frequently returns to her hometown of Zagreb, Croatia to take care of her elderly mother. Her widowed mother has had a stroke: she uses a walker and her language was affected so that she often uses the wrong word. This leads to some humorous conversations between mother and daughter:

The first section "Go There – I Know Not Where – and Bring Me Back a Thing I Lack" has no speculative fiction elements. It is written in the first person. The narrator is a famous author who frequently returns to her hometown of Zagreb, Croatia to take care of her elderly mother. Her widowed mother has had a stroke: she uses a walker and her language was affected so that she often uses the wrong word. This leads to some humorous conversations between mother and daughter:

"Bring me the…."

"What?"

"That stuff you spread on bread."

"Margarine?"

"No."

"Butter?"

"You know it’s been years since I used butter!"

"Well, what then?"

She scowls, her rage mounting at her own helplessness. And then she slyly switches to attack mode.

"Some daughter if you can’t remember the bread spread stuff!"

"Spread? Cheese spread?"

"That’s right, the white stuff," she says, offended, as if she had resolved never to again utter the words ‘cheese spread.’" (11)

I think my favorite one is when she asked for "the biscuits, the congested ones," instead of the digestive ones. (11-12)

We learn that the mother is Bulgarian and came to Croatia as a young wife. Some of her most treasured curios represent Bulgaria or are mementos of her early life. The daughter decides that she wants to visit Bulgaria as her mother’s bedel: "[c]enturies ago the wealthy would send someone else off on the hajj or the army in their stead as a bedel, a paid surrogate" (41). The daughter wants to bring back pictures of her mother’s city so that her mother can remember her youth. She enlists the help of a Bulgarian fan, Aba, who had written the author earlier, wanting to visit her in Croatia. Aba, a student in folklore, was in Croatia on an academic fellowship. The author was unable to meet Aba but facilitated a relationship between her mother and Aba, as fellow Bulgarians. The mother and Aba hit it off, so the daughter later arranges for Aba to accompany her while in Bulgaria. Her best-laid plans of "bedelship" go astray: she finds her mother’s hometown a victim of the communist and post-communist economies and finds the locations of her mother’s home and school changed and worn down; she also finds Aba annoying because the young fan wants to quote the author’s writing back to her. Thus, this first section is a look at aging, relationships and post-communist Eastern Europe.

We learn that the mother is Bulgarian and came to Croatia as a young wife. Some of her most treasured curios represent Bulgaria or are mementos of her early life. The daughter decides that she wants to visit Bulgaria as her mother’s bedel: "[c]enturies ago the wealthy would send someone else off on the hajj or the army in their stead as a bedel, a paid surrogate" (41). The daughter wants to bring back pictures of her mother’s city so that her mother can remember her youth. She enlists the help of a Bulgarian fan, Aba, who had written the author earlier, wanting to visit her in Croatia. Aba, a student in folklore, was in Croatia on an academic fellowship. The author was unable to meet Aba but facilitated a relationship between her mother and Aba, as fellow Bulgarians. The mother and Aba hit it off, so the daughter later arranges for Aba to accompany her while in Bulgaria. Her best-laid plans of "bedelship" go astray: she finds her mother’s hometown a victim of the communist and post-communist economies and finds the locations of her mother’s home and school changed and worn down; she also finds Aba annoying because the young fan wants to quote the author’s writing back to her. Thus, this first section is a look at aging, relationships and post-communist Eastern Europe.

The second section, "Ask Me No Questions and I’ll Tell You No Lies," continues the theme of playing with language that Ugresic began in the first section. One character, Beba, says the wrong word when nervous which leads her to say things like "Have a nice lay," when she means to say "Have a nice day." This playfulness continues throughout section two whose genre is closest to magical realism. It is full of improbable happenings and unbelievable coincidences that the characters never seem to notice. Also all the characters seem more symbolic and less real. Each seems like an archetype for an idea that I don’t quite grasp. (This is not a criticism. I didn’t feel lost at all.)

In this section, three old Croatian ladies, Pupa, Kukla, and Beba, ranging in age from sixty to eighty (or maybe more), visit the Wellness Centre, a spa in the Czech Republic. Their only connection to section one is that Pupa is mentioned there as one of the mother’s friends. Most of the men that the women meet in this section are part of the beauty and anti-aging industry. Mr. Shaker is an American who owns a business that sells pills, potions, and remedies, "bearing the food label supplement" (92). His American market is collapsing because reports are emerging that his remedies "pump up muscles" but "reduced potency" (93). So now he is looking into the "post-communist market" (93). Dr. Topolanek, the owner of the Wellness Centre, makes his living via "human vanity," selling his theory of longevity as well as spa treatments and massages (98). Finally, the old women meet Mevludin, a young Bosnian refugee, who works as a masseur at the Centre. The women spend a fantastic six days at the Centre. The endings are "happy" for Pupa, Kukla, and Beba, but they each travel from the spa into unknown worlds and challenges.

Here Ugresic criticizes the cult of youth and beauty. Her Croatian perspective is interesting because in Eastern Europe this cult is directly tied to post-communist capitalism. Dr. Topolanek sees his generation’s revolution as an internal one, one that allows people to change their bodies to whatever they want them to be. One of the best moments of this section shows Beba, who has been portrayed as an airhead up to this point, relaxing in a bath of warm chocolate (one of the therapeutic treatments) and musing upon the reproduction of Renior’s Woman with Parrot, hung on the wall. Beba’s thoughts carry us through an art history lecture that connects parrots with women’s sexuality in western art. This is a fun (and unexpected) tangent, but again illustrates why the book appealed to the Tiptree jury.

Here Ugresic criticizes the cult of youth and beauty. Her Croatian perspective is interesting because in Eastern Europe this cult is directly tied to post-communist capitalism. Dr. Topolanek sees his generation’s revolution as an internal one, one that allows people to change their bodies to whatever they want them to be. One of the best moments of this section shows Beba, who has been portrayed as an airhead up to this point, relaxing in a bath of warm chocolate (one of the therapeutic treatments) and musing upon the reproduction of Renior’s Woman with Parrot, hung on the wall. Beba’s thoughts carry us through an art history lecture that connects parrots with women’s sexuality in western art. This is a fun (and unexpected) tangent, but again illustrates why the book appealed to the Tiptree jury.

The third section continues on this scholarly tone. It begins with a letter that Dr. Aba Bagay, presumably the Bulgarian folklore student in section one, writes to an unknown editor who has asked her to read a manuscript and "explicate the correspondences between [the] author’s text and the myth of Baba Yaga" (239). The remainder of the section is her response, "Baba Yaga for Beginners," which discusses symbols related to Baba Yaga, supporting these with quotations from Eastern European myths and legends as well as quotations from scholars in the field, such as Maria Gimbutas and Marina Warner. Aba includes discussions of Baba Yaga’s name, her connection with witches and cannibalism and all her symbols, such as the hut, the mortar and pestle, birds and eggs. After each part, Aba provides "Remarks" that analyze the fictional author’s text in reference to the topic she just explained.

The surprising part is that the text that Aba is reading and commenting upon is made up of the two sections we just read. So, effectively, we have an author in the guise of an academic analyzing the book she just wrote. Ugresic shows her readers all of the Baba Yaga symbols and allusions that she included and they missed (at least many were missed on my part). For example, following her discussion of the hut, Aba writes:

Returning home, your author returns to the maternal ‘hut’ and repeats the initiation rite for the nth time. She must respect the law of Baba Yaga’s hut, otherwise Baba Yaga will eat her up. (263)

I’ve tried to find some other examples, but many of them give away too much about the plot. Just trust me; I couldn’t wait to finish each part so that Aba could connect my new knowledge of Baba Yaga to the previous plots. This set up makes for a very rich reading experience. I’ve never read a book before that taught its readers how to read it. I enjoyed being educated about the myth of Baba Yaga in this unorthodox manner.

I’ve tried to find some other examples, but many of them give away too much about the plot. Just trust me; I couldn’t wait to finish each part so that Aba could connect my new knowledge of Baba Yaga to the previous plots. This set up makes for a very rich reading experience. I’ve never read a book before that taught its readers how to read it. I enjoyed being educated about the myth of Baba Yaga in this unorthodox manner.

The ending brings in an element of the supernatural and that, along with the heavy dose of myths and folklore in section three and the magical realism of section two, shows me why this book was nominated for and won the Tiptree Award, even though at first glance this is not an obvious candidate. I found this book a very pleasurable read because I was continually intrigued about the way the story was being told.

Forays into Fantasy: Edgar Rice Burroughs One-Hundred Years On

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State College in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. Recently, he began branching out into fantasy, and was surprised by the diversity of the genre. It’s not all wizards, elves, and dragons! Scott’s new blog series, Forays into Fantasy, is an SF fan’s exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, building up an understanding of the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

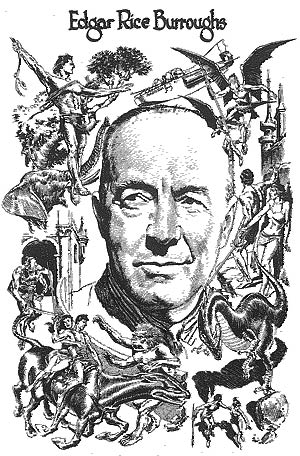

Around age eleven, Edgar Rice Burroughs was my favorite writer, and I devoured all of his books I could find. Rereading Burroughs’ first two novels today–A Princess of Mars (originally serialized in 1912 as "Under the Moons of Mars") and Tarzan of the Apes (serialized later in 1912), both of which have just been reprinted in beautiful facsimile editions by the Library of America–it’s harder to overlook the weaknesses, but the appeal remains clear. The prose is often awkward, incredible plot coincidences abound, relationships are simplistic, race and gender assumptions are problematic (more on that below), yet all these problems are (mostly) redeemed in the best of Burroughs’s novels by the relentless storytelling imagination and energy at work. Over one-hundred million copies sold, and counting…

Around age eleven, Edgar Rice Burroughs was my favorite writer, and I devoured all of his books I could find. Rereading Burroughs’ first two novels today–A Princess of Mars (originally serialized in 1912 as "Under the Moons of Mars") and Tarzan of the Apes (serialized later in 1912), both of which have just been reprinted in beautiful facsimile editions by the Library of America–it’s harder to overlook the weaknesses, but the appeal remains clear. The prose is often awkward, incredible plot coincidences abound, relationships are simplistic, race and gender assumptions are problematic (more on that below), yet all these problems are (mostly) redeemed in the best of Burroughs’s novels by the relentless storytelling imagination and energy at work. Over one-hundred million copies sold, and counting…

Burroughs was the most popular fantastic writer of the first third of the twentieth century, and it was during this period that the fantastic became “ghettoized” as it moved into the realm of the pulps, while mainstream writers for the most part stopped delving into the fantastic. As Paul Kincaid writes in “American Fantasy 1820–1950” (in The Cambridge Companion to Fantasy Literature):

“By the 1920s and 1930s the freedom that had allowed Jack London [and, earlier, Mark Twain or Henry James, among others] to move readily between realism and the fantastic was becoming more restricted. A mode now most readily identified with the smutty comedies of [Thorne] Smith and [James Branch] Cabell or, more damningly, with the grotesque horrors of Lovecraft and the crude, highly coloured adventures of [Robert E.] Howard could not be employed for serious literary purposes.”

As reading for pleasure became more widespread due in part to the development of low-cost “dime novels” and pulp magazines, the literary divide widened. The three main branches of the pulp fantastic were exemplified and inspired by Burroughs’ “science fantasy” adventures, Howard’s sword and sorcery (Conan, etc.), and Lovecraft’s weird fiction. Writers with serious literary ambitions no longer wanted to be associated with a mode of writing increasingly linked to the pulps.

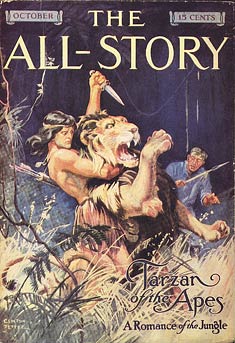

Burroughs got started earlier than Lovecraft or Howard and, reading him today, I think of him as the ultimate pulp writer–embodying both the positive and negative aspects of those early magazines, as well as informing all who would follow in his footsteps. Burroughs famously turned to writing relatively late, his military ambitions during the 1890s having been quashed. He failed to get into West Point or to be chosen as one of Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, but did spend some time in the cavalry in Arizona before being discharged for health reasons–an experience that helped inform the opening chapters of Princess–before attempting and abandoning a series of business ventures during the 1900s. He tried writing in part out of desperation, needing to support his young family, after reaching the conclusion that he could write better stories than the majority he was reading in the pulps of the time. (He was right!) His two best-known novels, both of which would spawn long-running series, both appeared in The All-Story magazine in 1912, the year Burroughs turned thirty-seven.

Burroughs got started earlier than Lovecraft or Howard and, reading him today, I think of him as the ultimate pulp writer–embodying both the positive and negative aspects of those early magazines, as well as informing all who would follow in his footsteps. Burroughs famously turned to writing relatively late, his military ambitions during the 1890s having been quashed. He failed to get into West Point or to be chosen as one of Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, but did spend some time in the cavalry in Arizona before being discharged for health reasons–an experience that helped inform the opening chapters of Princess–before attempting and abandoning a series of business ventures during the 1900s. He tried writing in part out of desperation, needing to support his young family, after reaching the conclusion that he could write better stories than the majority he was reading in the pulps of the time. (He was right!) His two best-known novels, both of which would spawn long-running series, both appeared in The All-Story magazine in 1912, the year Burroughs turned thirty-seven.

By his death in 1950, Burroughs had, in the prolific pulp tradition, published nearly seventy novels, and several more appeared posthumously. Along with the Barsoom (Mars) series, which eventually included eleven books, and the Tarzan series (twenty-four books), the trilogy beginning with The Land That Time Forgot probably remains best-known today. In addition, he wrote the Carson of Venus series, the Pellucidar hollow-Earth series beginning with At the Earth’s Core (which included a Tarzan crossover) and numerous other genre stories, as well as a few attempts at Westerns and contemporary fiction. To my mind, Burroughs peaked in the 1920s, with novels like Tarzan the Untamed (1920) and The Chessmen of Mars (1922), and both series are worth pursuing for readers who enjoy the opening books. After the ‘20s, however, diminishing returns set in, as will be clear to anyone who attempts to get through the last few volumes of the two series, or compares the tired-seeming Venus novels (1934–1946) to the earlier Mars books. Even as an enthusiastic adolescent, I think I gave up after sixteen or eighteen Tarzan novels.

Tarzan, of course, would live on in films, television, and comics, most of which greatly annoyed fans of the books, since they tended to leave out the more fantastic aspects (ancient lost cities, underground civilizations, dinosaurs, immortality drugs), but most importantly because they deemphasized the most interesting aspect of Tarzan’s character–his dual existence as a primordial jungle denizen and a highly intellectual English aristocrat. The combination makes him a superman. (And certainly, one of the impacts of the popularity of Tarzan and other pulp heroes would be on the creation of superhero comics beginning in the late ‘30s.)

Tarzan, of course, would live on in films, television, and comics, most of which greatly annoyed fans of the books, since they tended to leave out the more fantastic aspects (ancient lost cities, underground civilizations, dinosaurs, immortality drugs), but most importantly because they deemphasized the most interesting aspect of Tarzan’s character–his dual existence as a primordial jungle denizen and a highly intellectual English aristocrat. The combination makes him a superman. (And certainly, one of the impacts of the popularity of Tarzan and other pulp heroes would be on the creation of superhero comics beginning in the late ‘30s.)

Tarzan is really Lord Greystoke, whose parents were stranded on the African coast following a mutiny by the crew of the ship they were traveling on. Lady Alice died soon after, leaving a despairing father with no way to feed the infant. When a band of great apes–an invented species that seems to be the “missing link” between apes and humanity, with the rudiments of a spoken language–breaks into the cabin and kills Lord Greystoke, a female ape who had just lost her own baby adopts the boy and forces the rest of the band to tolerate Tarzan (“white skin” in the ape language) and allow her to raise him as one of them.

Despite having no direct contact with people, Tarzan does gain access to his parents’ cabin. Sitting with their skeletons, he discovers books, including, crucially, an illustrated dictionary, and his hereditary intelligence kicks in as he, amazingly, teaches himself to read. Once he started to identify groups of letters with accompanying pictures, “his progress was rapid… and the active intelligence of a healthy mind endowed by inheritance with more than ordinary reasoning powers” took over. For Burroughs, the aristocratic white man is clearly the peak of evolution, and even being brought up by apes cannot prevent the “higher” qualities from asserting themselves. Later, meeting Jane Porter brings his hereditary nature to the fore: “It was the hall-mark of his aristocratic birth, the natural outcropping of many generations of fine breeding, and hereditary instinct of graciousness which a lifetime of uncouth and savage training could not eradicate.” The impact of heredity and environment, and the conflicting appeals of his own kind and jungle life, will remain central to Tarzan’s character.

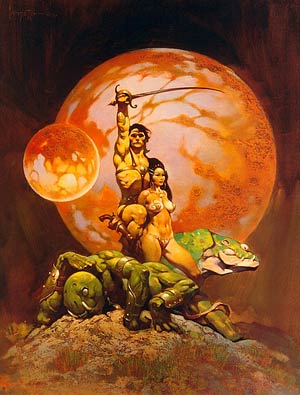

In A Princess of Mars, John Carter is similarly presented as a superior white aristocrat (an American southerner, in his case), who becomes the greatest man on Mars, just as Tarzan surpasses the rest of humanity due to his superior intelligence and character. Carter’s “features were regular and clear cut, his hair black and closely cropped, while his eyes were of a steel grey, reflecting a strong and loyal character, filled with fire and initiative. His manners were perfect, and his courtliness was that of a typical southern gentleman of the highest type.” Even his family’s slaves “fairly worshipped the ground he trod”! All in all, Carter is a “splendid specimen of manhood,” irresistible to the aristocratic Barsoomian princess Dejah Thoris: “Was there ever such a man! she exclaimed. ‘I know that Barsoom has never before seen your like… Alone, a stranger, hunted, threatened, persecuted, you have done in a few short months what in all the past ages of Barsoom no man has ever done.” As for Tarzan, Jane “noted the graceful majesty of his carriage, the perfect symmetry of his magnificent figure and the poise of his well shaped head upon his broad shoulders. What a perfect creature! There could be naught of cruelty or baseness beneath that godlike exterior. Never, she thought, had such a man strode the earth since God created the first in his own image.”

In A Princess of Mars, John Carter is similarly presented as a superior white aristocrat (an American southerner, in his case), who becomes the greatest man on Mars, just as Tarzan surpasses the rest of humanity due to his superior intelligence and character. Carter’s “features were regular and clear cut, his hair black and closely cropped, while his eyes were of a steel grey, reflecting a strong and loyal character, filled with fire and initiative. His manners were perfect, and his courtliness was that of a typical southern gentleman of the highest type.” Even his family’s slaves “fairly worshipped the ground he trod”! All in all, Carter is a “splendid specimen of manhood,” irresistible to the aristocratic Barsoomian princess Dejah Thoris: “Was there ever such a man! she exclaimed. ‘I know that Barsoom has never before seen your like… Alone, a stranger, hunted, threatened, persecuted, you have done in a few short months what in all the past ages of Barsoom no man has ever done.” As for Tarzan, Jane “noted the graceful majesty of his carriage, the perfect symmetry of his magnificent figure and the poise of his well shaped head upon his broad shoulders. What a perfect creature! There could be naught of cruelty or baseness beneath that godlike exterior. Never, she thought, had such a man strode the earth since God created the first in his own image.”

The racial implications are uncomfortable to the modern reader, but they are not as simplistically racist as they might at first appear. Both characters are the only white men in their respective worlds, and this is seen as a source of their superiority. Yet both are more at home in their adopted worlds than with their own kind. The racism is accompanied by the idea that the “lower” races (apes, blacks, Tharks, etc.) have positive qualities that have been lost by modern “civilized” whites. Carter is more at home with the green Tharks and red Martians, just as Tarzan feels the pull of jungle life whenever he returns to the constraints of civilization. And, despite the implication of miscegenation, Carter marries red-skinned Dejah Thoris, and the couple’s son will hatch from an egg. (Exactly how this works is happily never explained, and this is the sort of thing that, to me, makes Burroughs a fantasy rather than a science fiction writer.)

Carter is the embodiment of the Western hero suited for a frontier life–a life no longer available to him at home, but possible on Barsoom, which can be seen as an extension of the “manly” frontier life Burroughs himself had longed for in his military years. And Tarzan’s superiority to other men is not just because he is a white aristocrat in black Africa, but also because his upbringing by the apes has freed him from the constraints of civilization. Thus, it is the combination of heredity and upbringing that makes him superior to both Africans and whites. After learning the ways of civilization, which Tarzan/Greystoke takes to quite easily, he never loses the call of the wild.

Carter is the embodiment of the Western hero suited for a frontier life–a life no longer available to him at home, but possible on Barsoom, which can be seen as an extension of the “manly” frontier life Burroughs himself had longed for in his military years. And Tarzan’s superiority to other men is not just because he is a white aristocrat in black Africa, but also because his upbringing by the apes has freed him from the constraints of civilization. Thus, it is the combination of heredity and upbringing that makes him superior to both Africans and whites. After learning the ways of civilization, which Tarzan/Greystoke takes to quite easily, he never loses the call of the wild.

“Tarzan had no sooner entered the jungle than he took to the trees and it was with a feeling of exultant freedom that he swung once more through the forest branches. This was life! Ah, how he loved it! Civilization held nothing like this in its narrow and circumscribed sphere, hemmed in by restrictions and conventionalities. Even clothes were a hindrance and a nuisance. At last he was free. He had not realized what a prisoner he had been.”

Throughout the series, Greystoke would be drawn back to civilization by his family and hereditary obligations, but he would always long for and ultimately return to the jungle–his true home. Similarly, at the end of A Princess of Mars, when Carter returns to Earth as mysteriously as he had originally appeared on Mars, all he can think of is his desire to return to the dying red planet. “I can see her shining in the sky through the little window by my desk, and tonight she seems calling to me again.” He, too, will return for the sequel.

Tarzan became one of the best known character creations of the twentieth century, but it is Barsoom that would have the biggest impact on fantasy and science fiction. Ray Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles, with its dying planet crisscrossed with canals and home to ancient ruins of once-great civilizations, can be traced back to Burroughs, as can the entire subgenre of science fantasy and planetary romance, as traced through the works of Leigh Brackett (Sea-Kings of Mars), Jack Vance (Big Planet), Michael Moorcock (the Michael Kane trilogy), Gene Wolfe (The Book of the New Sun), George Lucas (Star Wars), and countless others. In a planetary romance, the alien planet and its exploration are important aspects of the story; the means of getting there are not. In Princess, Carter, longing to reach Mars, “stretched out my arms toward the god of my vocation and felt myself drawn with the suddenness of thought through the trackless immensity of space.” Such stories are often marketed as science fiction, but they are distinguished from fantasy only in that the imaginary settings are on other planets rather than undefined earthly realms like Middle Earth or Westeros.

Burroughs’s influence, then, arises from the subgenre he pioneered–exciting adventure stories set in fantastic locales with one foot in reality, and he is seen as the progenitor of science fantasy and the planetary romance. But is he still worth reading? The books have not avoided becoming dated (Tarzan more so than Barsoom), but Burroughs is a natural storyteller, and it’s easy to see why these books were so compelling to legions of readers over the years, especially younger readers like my ten-year-old self, for which Burroughs has served as a major gateway into fantasy and science fiction. It could be argued that genre readers no longer need to bother with Burroughs, but if so, this is because his influence has been so thoroughly absorbed into the field, even those who haven’t read the originals have still, in a sense, internalized them by reading so many works influenced by them. Apparently, one of the criticisms of the recent John Carter film was that, for many viewers, it seemed overly familiar and unoriginal. This is the potential fate of the most influential stories–decades of homage and imitation can make the original seem unoriginal!

Burroughs’s influence, then, arises from the subgenre he pioneered–exciting adventure stories set in fantastic locales with one foot in reality, and he is seen as the progenitor of science fantasy and the planetary romance. But is he still worth reading? The books have not avoided becoming dated (Tarzan more so than Barsoom), but Burroughs is a natural storyteller, and it’s easy to see why these books were so compelling to legions of readers over the years, especially younger readers like my ten-year-old self, for which Burroughs has served as a major gateway into fantasy and science fiction. It could be argued that genre readers no longer need to bother with Burroughs, but if so, this is because his influence has been so thoroughly absorbed into the field, even those who haven’t read the originals have still, in a sense, internalized them by reading so many works influenced by them. Apparently, one of the criticisms of the recent John Carter film was that, for many viewers, it seemed overly familiar and unoriginal. This is the potential fate of the most influential stories–decades of homage and imitation can make the original seem unoriginal!

Next up: The Enchanter stories of L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt…

GMRC Review: The Wind’s Twelve Quarters by Ursula K. Le Guin

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his sixth for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

Guest Blogger and WWEnd member, valashain, reviews science fiction and fantasy books on his blog Val’s Random Comments which we featured in a previous post: Five SF/F Book Blogs Worth Reading. Val has posted many great reviews to WWEnd and this is his sixth for the GMRC. Be sure to visit his site and let him know you found him here.

The Wind’s Twelve Quarters is Ursula K. Le Guin‘s first collection of short fiction and was published in 1975. Quite unusual for a single author short science fiction collection, it is still in print decades after it has been first published. It is generally regarded as the strongest of her collections of short fiction. Not having read the others, I don’t have an opinion on that but I did think The Wind’s Twelve Quarters is a bit of a mixed bag. It contains a total of seventeen stories, presented more or less in the order they were published and cover the period between her first publication in 1962 and 1974, by which time she had published some of her best know and most critically acclaimed novels. Le Guin chose this order so the reader could experience her growth as an author. In that respect the collection certainly succeeds. The later stories are much stronger than the earlier ones. Most of the stories have a short introduction by Le Guin about the inspiration for the story and the editorial changes compared to the original magazine publications. A fair number of stories in the collection are what Le Guin calls psychomyths. These stories are hard to pin down but they are independent of setting and often have a surreal quality to them. Le Guin herself puts it like this:

…more or less surrealistic tales, which share with fantasy the quality of taking place outside any history, outside of time, in that region of the living mind which – without invoking any consideration of immortality – seems to be without spatial or temporal limits at all.

Le Guin on psychomyths – Foreword

Most of the stories that are not tied to her novels seem to fall into this category. Quite a few of the stories are linked to her novels though. There are Earthsea stories in this collection as well as stories set in the Hainish universe and even a story tied to her novel The Dispossessed (1974). The opening story, "Selmy’s Necklace" (1964), is essentially the prologue of Le Guin’s first novel, Roccanon’s World (1966). It is set in her Hainish future history and in some ways, reminded me a lot of some of Poul Anderson‘s Technic Civilization stories. It is seen mostly form the point of view of a member of a less technically advanced race trying to retrieve an heirloom that that was lost decades ago. She doesn’t properly comprehend the consequences of her request to be allowed to visit the aliens but to the reader the tragedy that is unfolding is quite clear. A science fiction story written in language that is more often found in fantasy. This story clearly shows why Le Guin usually doesn’t make too rigorous a distinction between the two.

The second story is "April in Paris" (1962) is the earliest story in the collection and Le Guin’s first sale. I can’t say I liked it much. I guess you could say it is a time travel story. I thought it was pretty predictable with more than a bit wish fulfilment in it. Le Guin then moves on to a story that is also a bit predictable but conceptually more interesting. "The Masters" (1963) deals with a man who is brought up in a very strict guild like environment where things have always been done a certain way and where deviating from this way, or trying to improve upon it, is heresy. He can’t resist the lure of progress though. There is another story that is thematically related to this one in the collection. "The Masters" is very dark, full of despair. Stylistically probably not the strongest piece but certainly an interesting one. "The Darkness Box" (1963), like "The Masters" is a piece that can be considered a fantasy or perhaps an early psychomyth. It’s a story with a sense of inevitably about it, of pointless repetition. Not a story that makes one feel happy although one of the characters sees things differently.

"The Word of Unbinding" and "The Rule of Names" (both 1964) are Le Guin’s first Earthsea stories. I haven’t read any of the Earthsea novels so putting them into the perspective of the whole series is going to be a bit difficult. I think they lay the groundwork for the system of magic found in the Earthsea novels. A system that appears to be quite sophisticated judging from these few pages. The stories are uncut fantasy, the only ones in this collection. I will have to read one of the Earthsea novels to be sure but I think I prefer Le Guin’s science fiction. Still, Earthsea is on the to read list.

"Winter’s King" (1969) is another story tied to one of Le Guin’s novels. It is set on the same planet as The Left Hand of Darkness (1969), a novel in the Hainish cycle that is also on my to read list. The version in this collection has been changed to fit the novel more closely and features the wintry world of Gethen. Le Guin plays with titles and particular pronouns to underline the androgyny or the inhabitants. The story itself is one of mind control and a King struggling to do what is best for the kingdom. It certainly makes me curious about the novel. Gethen seems like an intriguing place and the way gender appears to play no role in society opens up all kinds of interesting possibilities. Something that struck me about this story is how, like in "Selmy’s Necklace", Le Guin presents a technologically less advanced society in a science fiction story. Some readers would say there is a hint of fantasy in this story.

"The Good Trip" (1970) is a story that is probably contemporary. As the title suggests it is about drug use among other things. The trip makes it quite a strange story full of weird cognitive leaps and odd situations. Le Guin didn’t seem to be opposed to people experimenting with LSD at the time, which was no doubt frowned upon. She does mention in the introduction that she feels that "people who expand their consciousness by living instead of taking chemicals usually come back with much more interesting reports of where they’ve been." Now there is a bit of wisdom for you.