The Universe Wants You Dead: The Return of Cosmic Horror

It’s a phrase I expect to find written in fat, drippy letters on the cover of an EC comic book from the 1950’s. Or one of the empty promises hurled at the audience in the previews for what will prove to be a predictably ordinary 1940’s horror film: Fiendish Tortures!… Ghastly Terrors!!… Cosmic Horror!!!

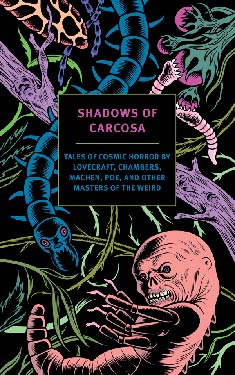

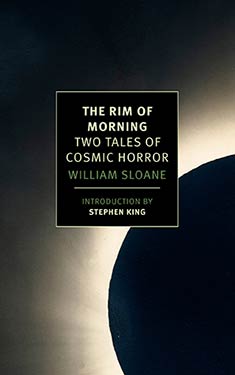

It is not a term I expect to find in the subtitle of not one but two current releases from New York Review Book Classics – Shadows of Carcosa, Tales of Cosmic Horror edited by D. Thin; and, The Rim of Morning, Two Tales of Cosmic Horror by William Sloane. NYRB Classics is an admirably eclectic sampling of world literature where major if obscure works of European Modernism find themselves shelved alongside noirish crime fiction of both U.S. and European vintages and the novels, memoirs and travel journals of excellent prose stylists who the editors have rightly decided deserve a fresh hearing.

But “Cosmic Horror”?

First of all, what are they talking about? And are they just trying to avoid the even pulpier term, Weird Fiction, which is, by the way, what they are talking about. Weird Fiction found its home in the classic pulp magazine Weird Tales. That magazine had a long run from 1923 – 1954 and several incarnations since, one of which remains in print. Hundreds of authors, many lost to time, appeared in the magazine, but it remains best known for the presence of H.P. Lovecraft in its early issues.

First of all, what are they talking about? And are they just trying to avoid the even pulpier term, Weird Fiction, which is, by the way, what they are talking about. Weird Fiction found its home in the classic pulp magazine Weird Tales. That magazine had a long run from 1923 – 1954 and several incarnations since, one of which remains in print. Hundreds of authors, many lost to time, appeared in the magazine, but it remains best known for the presence of H.P. Lovecraft in its early issues.

Although Lovecraft acknowledged his many forbearers, his florid, visionary style defined the genre. This new NYRB anthology quotes him on the back cover. He writes that in the true weird tale —

An atmosphere of breathless and unexplainable dread of outer, unknown forces must be present; a hint of that most terrible conception of the human brain – a malign and particular suspension of defeat of those fixed laws of nature what are our only safeguard against the assaults of chaos and the daemons of unplumbed space.

Lovecraft’s was a cosmic vision, and later writing on the genre introduced and refined the term “cosmic horror.” A Wikipedia entry covers the field but has the unfortunate term “comicism” as a title. The website TV Tropes takes a more casual and entertaining approach. They offer a five-question quiz readers can use when confronting possible entries to the cosmic horror canon. Two negative answers means that you have slipped into the watered down realm of “Lovecraft Lite.”

With the first season of the HBO series True Detective, the Cosmic Horror genre wormed its way into the minds of a great swath of the American public that had probably never considered reading Lovecraft or Weird Fiction. The ritualistic murders and the decadent sect that the protagonists uncovered in the American South made references to The King in Yellow and Carcosa. Viewers and commentators rushed to the internet to unpack those references and found the peculiar 1895 work by R.W. Chambers, a popular if not particularly good writer of the time who specialized in romance novels but turned out several anthologies of weird fiction. In Chamber’s work, The King in Yellow is the name of a forbidden play, a work so diabolical that reading it, particularly reading Act Two, will drive a person mad. The play is set in Carcosa, an imaginary city Chambers borrowed from an 1891 Ambrose Bierce short story. The HBO series employs the terms divorced from any of their previous fictional uses, but weirdness and cosmic horror is all about hints and evocations. True Detective’s grand guignol set pieces and its pessimistic denouement did the tradition proud.

Shadows of Carcosa includes both the Bierce short story and a tale from the Chambers collection. It’s a chronological anthology that begins with Edgar Allan Poe and ends with Lovecraft, therefore much of what is here is “proto-weird.” It’s a progression of established tales that allows editor D. Thin to make a case for a genuine tradition. Genre fans will find mostly familiar material with a few hard-to-come-by entries, and such terror masterpieces as Poe’s “MS Found in a Bottle” or Algernon Blackwood’s “The Willows” are always worth rereading in a new context. For people only familiar with Dracula, Bram Stoker’s “The Squaw” proves that he was a refined purveyor or Victorian frights that had found their way into a more modern world than their Gothic predecessors. Arthur Machen is an enthusiasm I have long aspired to without ever quite attaining, but rereading “The White People” makes me want to have another go at him. Including Henry James and Walter de la Mare may be a stretch for the editor, but I am not one to complain given the quality of their stories.

This was my first encounter with M.P. Shiel, who I know wrote The Purple Cloud (1901), an apocalyptic novel kept in print by Penguin Classics. “The House of Sounds,” his story collected here, is an off-the-rails variation on the theme of a young man’s journey to the remote home of an old college friend. I am not surprised to learn that his contemporaries considered Shiel “gorgeously mad,” and that he had become a “reclusive religious maniac” by the time of his death.

Prose as feverish as Shiel’s or Lovecraft’s, and situations as extreme as those that fill these stories, ask the committed reader not to find the enterprise ridiculous. The writing at its best, or at its worst – these terms can become relative – may be bonkers, but woven through the lurid fireworks are passages effective as both visceral horror and exciting of explorations of extreme psychological states. The diarist in Poe’s “MS Found in a Bottle” is trapped on a ship blown off course and headed for oblivion. His lucidity is the last remnant of his humanity.

To conceive the horror of my sensations is, I presume, utterly impossible; yet a curiosity to penetrate the mysteries of these awful regions predominates even over my despair, and will reconcile me to the most hideous aspect of death. It is evident that we are hurrying onwards to some exciting knowledge – to some never-to-be-imparted secret, whose attainment is destruction.

To conceive the horror of my sensations is, I presume, utterly impossible; yet a curiosity to penetrate the mysteries of these awful regions predominates even over my despair, and will reconcile me to the most hideous aspect of death. It is evident that we are hurrying onwards to some exciting knowledge – to some never-to-be-imparted secret, whose attainment is destruction.

The two William Sloane novels from the 1930’s gathered in The Rim of Morning may seem like tame stuff compared to the stories in D. Thin’s anthology. To Walk the Night and The Edge of Running Water were Sloane’s only two novels. He wrote a few stories, edited a couple of significant sf anthologies, but spent most of his career as the director of Rutgers University Press. Stephen King writes the admiring introduction to the NYRB volume, and he lets the reader know not to anticipate the kind of horror show that we have come to expect from the genre:

Sloane builds his stories in carefully wrought paragraphs, each one clear and direct. He is a man of the old school, who learned actual grammar in grammar school…and probably Latin at the high school and college levels.

King may be weeding out the sensation seekers, but, like King, I was hooked by the first sentence of each of Sloane’s novels. These openings promise the kind of storytelling I weaned myself on as a child and still find irresistible.

The form in which this narrative is cast must necessarily be an arbitrary one. In the main it follows the story pieced together by Dr. Lister and myself as we sat on the terrace of his Long Island house one night in the summer of 1936.

To Walk the Night

The man for whom this story is told may or may not be alive.

The Edge of Running Water

Sloane’s novels bring in university settings and academic protagonists, which is not surprising given his background. In To Walk the Night, two young men making their way in the New York City financial markets return to their alma mater for a homecoming football game. When they go to visit a favorite astronomy professor, they find him seated in the chair at his telescope in the school’s observatory and burned to a crisp. (Small North Eastern colleges have observatories in these types of stories the same way college professors have elaborate laboratories in their remote country homes – see The Edge of Running Water ff.) The deceased professor had recently acquired, to his ex-students’ surprise, a young, beautiful, otherworldly wife. To the reader’s surprise, when this woman shows up in Manhattan one of the young men falls under her spell, marries her, and moves to the desert. Distressed letters from the young husband brings his friend to Cloud Mesa and sets up Sloane’s final set piece, a conclusion that proves that this director of Rutger’s University Press knew how to put on quite a show.

In The Edge of Running Water, a young science professor answers a distressed message from his mentor who has retired – in disgrace – to some New England backwater. There he continues researches that may change the way we think about life and death. That sounds like the hackneyed plot to some minor, 1940’s Universal Studios Boris Karloff vehicle, and in fact it is. You can stream it on Your Tube under its more suitable Saturday matinee title, The Devil Commands. (I recommend it on principle, not having yet watched it myself.) Sloane squeezes all the action of his final novel into a forty-eight-hours and incorporates a love interest for the young protagonist, a creepy medium whose agenda may run counter to the aging professor’s best interests, and a possible murder. What the novel lacks in suspense it makes up for in characterization and a frenzied conclusion. Sloane’s novels may appeal to only a small segment of the horror market, but they definitely have their place in the history of American fantastic literature. They are best read on rainy afternoons.

NYRB Classics have sprinkled horror and science fiction through their lists, and these two volumes are welcomed additions. Two new titles do not mark a trend, but given the depth and quality of their crime list, weird fiction, cosmic horror, or however they choose to label it is a promising field should they choose to commit to it.

Book Gift Suggestions: Horror

![]()

It’s been a while since we created our suggestion list for Fantasy, and the Month of Horrors seemed like the perfect time to cobble together a list for Horror. Been looking for some good genre book recommendations you can pass along to non-genre or genre-beginner readers? Here are some works of fiction that will blow their minds and make them addicts just like you.

Today’s list contains half a dozen Horror books to knock the socks off the people who don’t have good genre taste… yet.

The Thing on the Doorstep and Other Weird Stories, by H. P. Lovecraft

The Thing on the Doorstep and Other Weird Stories, by H. P. Lovecraft

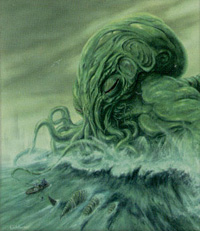

Arguably, you could hand a reader any collection of Lovecraft stories, and the effect would be just about the same. The master of weird fiction rotated regularly through just a few variations on his theme of supernatural terror: from intrusions out of the dream world to beautiful symbolic visions, from unnatural resurrections to polar-dwelling Elder Things, you can be sure that at least somebody will be losing his sanity, if not his lunch. Many of the stories in this volume also tie in to Lovecraft’s popular Cthulhu Mythos, so there’s plenty of temptation here to find more to read.

Perfect For: People who like old-timey scares and wish their steampunk novels had more unnatural geometry.

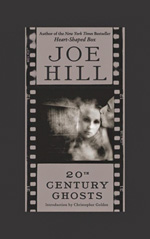

20th Century Ghosts, by Joe Hill

20th Century Ghosts, by Joe Hill

One might shy away from Hill’s collection of short stories in favor of his more popular novels, but 20th Century Ghosts has something for everybody to enjoy. As I wrote in my longer review last year, the stories that especially stand out are “20th Century Ghost” (about a dead girl who loves the movies too much to leave the theatre), “The Black Phone” (a terrifying tale of kidnapping and phone calls from the dead), “The Cape” (a spooky story of a… different kind of superhero), and “Voluntary Committal” (wherein one might easily be lost amidst the cardboard maze in the basement). Don’t miss out on Hill’s sequel to Dracula and his personal take on Kafka’s Metamorphosis, either.

Perfect For: Anyone who likes disturbingly surreal tales.

Dracula, by Bram Stoker

Dracula, by Bram Stoker

By far the most obvious recommendation on this list, you might be surprised how many people have never read the novel that sparked the popularity of the “romantic vampire” subgenre. Told entirely as an epistolary novel, Dracula follows the ever-shifting fortunes of a small group of English aristocrats as an ancient Transylvanian vampire decides to hitch a ride to their homeland from the old country. It’s both a look at the fragility of Victorian mores, and awe at the power of the mysterious foreign “other.” Arguably also a yearning for a spiritually-enriched world that the Enlightenment cast aside, Stoker’s novel offers a great deal even for a jaded, modern audience.

Perfect For: That friend who’s watched every Dracula movie.

House of Leaves, by Mark Z. Danielewski

House of Leaves, by Mark Z. Danielewski

Danielewski isn’t well known for his fiction outside of this novel, partly because he hasn’t written much else, but mostly because his other work is so rarified and abstract that it only appeals to a niche audience. However, House of Leaves was his first and most popular work, despite some aspects that a popular audience might find pretentious. This is a story told from the perspective of a young tattoo artist Johnny Truant, writing about a found manuscript detailing a documentary that does not seem to officially exist, The Navidson Record. It’s a narrative within a narrative within a narrative, copiously (and often erroneously) footnoted. The documentary concerns a preternaturally-shaped house, which may or may not be haunted, and which frequently changes its inner layout and dimensions. It’s hard to be both scary and erudite, but Danielewski manages.

Perfect For: Someone who’s ready to make the leap into metafiction.

The Sandman: Preludes and Nocturnes, by Neil Gaiman

The Sandman: Preludes and Nocturnes, by Neil Gaiman

Although Neil Gaiman has long had a reputation as a Horror writer, much of his fiction is simply Fantasy with a slight twist of Horror. Even most of his run on the Sandman comic series was more about Fantasy than Horror. But the first volume of this popular set definitely shows off Gaiman’s talent at writing Horror, albeit the sort influenced more by old Horror comics than novels. As he introduces the character of Morpheus, the King of Dreams, he is at great pains to remind us that Morpheus is also the King of Nightmares. The series found a larger audience after this first storyline, but I will always have a soft spot for this mash-up of Gothic and old-school comic book scares.

Perfect For: Wannabe goths and people wondering how Neil Gaiman got his start.

Inferno, by Dante Alighieri

Inferno, by Dante Alighieri

Ok, this one might be pushing it a little. There’s no doubt that much of today’s Horror fiction simply could not exist without Dante, but his medieval epic poem does not easily fit into the genre as we know it today. It also does not provide the thrills-n-chills normally associated with Horror. It is rather a more intellectual look at the horrors of the human spirit, and a sober acknowledgement of where they lead us. That being said, I would stack up the story told by Count Ugolino in the ninth circle of Hell about his betrayal by an archbishop to a slow and very cruel death against anything written by Stephen King or Clive Barker. You can also learn how Hell actually froze over a very, very long time ago.

Perfect For: Poetry lovers and those curious about ancient cosmologies.

Have anything you’d like to add to the list? Let us know in the comments!

H.P. Lovecraft: A Bit of a Pessimist

As part of our ongoing effort to underscore the classier side of genre literature, we’ve decided to keep pushing forward with our Genre Poetry series. We may be well out of the Month of Horrors, but that provides no safety from Friday the 13th! In keeping with the day’s traditional fears, this installment of Genre Poetry comes from the American patriarch of horror himself, H.P. Lovecraft, writing about what he knows best…

As part of our ongoing effort to underscore the classier side of genre literature, we’ve decided to keep pushing forward with our Genre Poetry series. We may be well out of the Month of Horrors, but that provides no safety from Friday the 13th! In keeping with the day’s traditional fears, this installment of Genre Poetry comes from the American patriarch of horror himself, H.P. Lovecraft, writing about what he knows best…

Despair

by H.P. LovecraftO’er the midnight moorlands crying,

Thro’ the cypress forests sighing,

In the night-wind madly flying,

Hellish forms with streaming hair;

In the barren branches creaking,

By the stagnant swamp-pools speaking,

Past the shore-cliffs ever shrieking;

Damn’d daemons of despair.Once, I think I half remember,

Ere the grey skies of November

Quench’d my youth’s aspiring ember,

Liv’d there such a thing as bliss;

Skies that now are dark were beaming,

Gold and azure, splendid seeming

Till I learn’d it all was dreaming—

Deadly drowsiness of Dis.But the stream of Time, swift flowing,

Brings the torment of half-knowing—

Dimly rushing, blindly going

Past the never-trodden lea;

And the voyager, repining,

Sees the wicked death-fires shining,

Hears the wicked petrel’s whining

As he helpless drifts to sea.Evil wings in ether beating;

Vultures at the spirit eating;

Things unseen forever fleeting

Black against the leering sky.

Ghastly shades of bygone gladness,

Clawing fiends of future sadness,

Mingle in a cloud of madness

Ever on the soul to lie.Thus the living, lone and sobbing,

In the throes of anguish throbbing,

With the loathsome Furies robbing

Night and noon of peace and rest.

But beyond the groans and grating

Of abhorrent Life, is waiting

Sweet Oblivion, culminating

All the years of fruitless quest.

(Thanks to the H.P. Lovecraft Archive for hosting this and so many other works from the author.)

Month of Horrors: End of Month Wrap-Up

Today isn’t just Halloween, it’s also the closing day of WWEnd’s Month of Horrors, our 31-day celebration of the Horror genre in conjunction with adding this genre to the site. We’ve decided to wrap up the festivities with a dialogue between Rico and me about the genre. We may not be the biggest Horror aficionados in the world, but we both love literature, and I think we are both curious to see how it fits in the pantheon of genres, and especially how it relates to Science Fiction and Fantasy, the long-time staples of the WWEnd site.

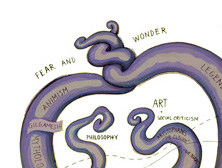

Jonathan: Ward Shelley in his infographic links genre fiction back into the primal emotions of Fear and Wonder. Arguably the Horror genre is far more about Fear than Wonder, though it often has its fair share of both. H. P. Lovecraft, of all people, occasionally wrote lyrically beautiful stories like “The White Ship” which were filled with wonder. But despite its primal roots, I don’t know of any previous body of literature that has focused so intently on the emotion of fear. In some ways, it reminds me of amusement park rides, which are built almost entirely to give the riders a thrill or a scare, the false feeling that their lives are in imminent physical danger even though everything is perfectly under control. I’ve often wondered if the thrill of fear is the primary draw for horror readers, if they are wanting to feel a “safe danger” like that of the amusement park ride. In other cases I suspect that the genre is a way of dramatically expounding on a philosophical or theological belief about the nature of the universe, the human condition, and the relationship between humanity and whatever cosmic powers might be. Do you have any thoughts on the genre from this perspective? Certainly I doubt that we will be able to fully unravel the mystery of any genre’s attraction—even Science Fiction is often more confounding than captivating to me—but I admire it if only as an outsider.

Jonathan: Ward Shelley in his infographic links genre fiction back into the primal emotions of Fear and Wonder. Arguably the Horror genre is far more about Fear than Wonder, though it often has its fair share of both. H. P. Lovecraft, of all people, occasionally wrote lyrically beautiful stories like “The White Ship” which were filled with wonder. But despite its primal roots, I don’t know of any previous body of literature that has focused so intently on the emotion of fear. In some ways, it reminds me of amusement park rides, which are built almost entirely to give the riders a thrill or a scare, the false feeling that their lives are in imminent physical danger even though everything is perfectly under control. I’ve often wondered if the thrill of fear is the primary draw for horror readers, if they are wanting to feel a “safe danger” like that of the amusement park ride. In other cases I suspect that the genre is a way of dramatically expounding on a philosophical or theological belief about the nature of the universe, the human condition, and the relationship between humanity and whatever cosmic powers might be. Do you have any thoughts on the genre from this perspective? Certainly I doubt that we will be able to fully unravel the mystery of any genre’s attraction—even Science Fiction is often more confounding than captivating to me—but I admire it if only as an outsider.

Rico: Horror does seem to have older roots than other genres. Whether it’s Odysseus trapped between the monster (Scylla) and a gaping nothingness (Charybdis), Hercules battling a hydra, or Jason facing the harpies, even the ancient Greeks felt the need for monstrous yarns. Lovecraft said this was because fear is our oldest emotion, especially fear of the unknown. In a lot of ways, it sort of drives us to find out what it is that scares us, so we can conquer it. Fear, then, is not so different from wonder.

Rico: Horror does seem to have older roots than other genres. Whether it’s Odysseus trapped between the monster (Scylla) and a gaping nothingness (Charybdis), Hercules battling a hydra, or Jason facing the harpies, even the ancient Greeks felt the need for monstrous yarns. Lovecraft said this was because fear is our oldest emotion, especially fear of the unknown. In a lot of ways, it sort of drives us to find out what it is that scares us, so we can conquer it. Fear, then, is not so different from wonder.

As to why horror is so attractive, however, we need a different explanation. Maybe one clue can be found in physiology. Sartre once observed that the symptoms of fear (dilation of the pupils, elevated heart rate, perspiration) also happen to occur when one falls in love. Two completely different conditions elicit the same bodily reactions. Because fear is so primal, it might be easier to frighten a reader than to make him/her fall in love. If the trill of a good scare gets me flushed in a way that is so love-like, why wouldn’t I enjoy it?

Jonathan: You mentioned both the Lovecraft and the ancient Greeks, but there’s a world of difference between the way each would approach a horrific tale. The Greeks had stories of monsters like Medusa and Typhon which, on the surface, are very similar to monsters like Lovecraft’s Cthulu, but while the Greek monsters might eat the occasional passerby and even level a mountain or two, Olympus could never truly lose the world to these monsters. Cthulu, on the other hand, will inevitably rise from the watery deeps to darken the sky and devour mankind. There’s the horror that is finite and destructible, like the Chimera and the Hydra, and then there’s the horror that devours not only people but hope. A classical tale of horror might end badly for some people, but it will also end with the sun still shining and regular people living their lives. A modern horror tale will often end with the emotional and psychological devastation of the protagonist, whose beliefs about the stability of the world have been crushed.

Jonathan: You mentioned both the Lovecraft and the ancient Greeks, but there’s a world of difference between the way each would approach a horrific tale. The Greeks had stories of monsters like Medusa and Typhon which, on the surface, are very similar to monsters like Lovecraft’s Cthulu, but while the Greek monsters might eat the occasional passerby and even level a mountain or two, Olympus could never truly lose the world to these monsters. Cthulu, on the other hand, will inevitably rise from the watery deeps to darken the sky and devour mankind. There’s the horror that is finite and destructible, like the Chimera and the Hydra, and then there’s the horror that devours not only people but hope. A classical tale of horror might end badly for some people, but it will also end with the sun still shining and regular people living their lives. A modern horror tale will often end with the emotional and psychological devastation of the protagonist, whose beliefs about the stability of the world have been crushed.

So while there is a kind of pleasurable (even love-like) thrill that can come from a frightening story, I don’t know that the Lovecraftian sort of total despair offers the same pleasure. David Hume once wrote about the stage tragedies of his day: “What [can be] so disagreeable as the dismal, gloomy, disastrous stories with which melancholy people entertain their companions?  The uneasy passion being there raised alone, unaccompanied with any spirit, genius, or eloquence, conveys a pure uneasiness, and is attended with nothing that can soften it into pleasure or satisfaction.” Do you think that modern horror perhaps offers the taste of that thrill without the pleasure, or am I being too harsh on it?

The uneasy passion being there raised alone, unaccompanied with any spirit, genius, or eloquence, conveys a pure uneasiness, and is attended with nothing that can soften it into pleasure or satisfaction.” Do you think that modern horror perhaps offers the taste of that thrill without the pleasure, or am I being too harsh on it?

Rico: I agree that there is a difference between the Greek stories and Lovecraft, but Lovecraft doesn’t define the genre. The world is still intact when the tell-tale heart stops beating, when the vampire finally gets staked, and when the last alien is flushed into space by Sigourney Weaver. Lovecraftian horror, it seems to me, is a special extremist sub genre. Of course, even it doesn’t find the world in tatters (there’d be no story if Hastur or Cthulu ever crossed over). It’s the threat of obliteration that makes the story exciting. In that sense, the Lovecraftian world really does share something in common with Odysseus and his men hovering on the brink of Charybdis, yet not quite falling in.

Also, although it’s true that the Olympic gods may not lose the world (well, there is one time, in the Iliad, when the Fates tell Zeus that he may defy them to save Troy, but that the cosmos would fall into chaos as a result), but humans certainly can lose their world. I’m thinking of Hecuba, for whom there can be no solace. Niobi (“all tears”) comes to mind. As in Lovecraft’s world, the gods take away everything.

Perhaps a better ancient analogue to Cthulu is Vishnu, the Hindu god whom Oppenheimer quoted as he reflected upon the nuclear horror he helped to create: “Now, I am become death, destroyer of worlds.”

Perhaps a better ancient analogue to Cthulu is Vishnu, the Hindu god whom Oppenheimer quoted as he reflected upon the nuclear horror he helped to create: “Now, I am become death, destroyer of worlds.”

Jonathan: Fair enough. In addition to the classical and modern horror narratives, it’s educational to look at the Medieval/Christian stories that most closely match the genre. Medieval poets loved singing about bizarrely chimeric beasts in addition to the demons and occult practitioners who frequently tormented the innocent. Meanwhile, Dante’s Inferno explored the greatest horror imaginable: everlasting damnation and torment. It’s a particularly interesting sort of horror, though, in that the one experiencing its pains has brought them upon himself. (Those in Dante’s version of Hell who are there by no vice of their own, like the unbaptized infants and the virtuous pagans, suffer no external pains.) When Dante tours the underworld, he is not witnessing the caprices of a cruel god, but the wasted lives of those who refused to do good and now suffer the consequences. The Medieval vision of Hell managed to combine the classical vision of celestial permanence and beauty with the all-consuming despair of a Lovecraftian apocalypse, as it’s inscribed on Hell’s doors: “Justice caused my high Architect to move… / The highest Wisdom, and the primal Love … / Abandon all hope you who enter here” (trans. Anthony Esolen).

To my mind, the best of the Horror genre is that which manages to keep both aspects of reality in play. When the balance tips entirely towards Tragedy (so to speak) or entirely in favor of Comedy, one feels that the poet or novelist isn’t being entirely honest about the way things are. Cormac McCarthy’s The Road is a magnificently-written novel, but it is arguably stuck in an emotional rut of bleak despair. As a counterpoint, Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings saga is a work which manages to drink the cup of futility to its last drop, without losing hope.

To my mind, the best of the Horror genre is that which manages to keep both aspects of reality in play. When the balance tips entirely towards Tragedy (so to speak) or entirely in favor of Comedy, one feels that the poet or novelist isn’t being entirely honest about the way things are. Cormac McCarthy’s The Road is a magnificently-written novel, but it is arguably stuck in an emotional rut of bleak despair. As a counterpoint, Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings saga is a work which manages to drink the cup of futility to its last drop, without losing hope.

Rich: That, it seems, is very much in keeping with Hallowe’en, which is a sort of twilight between the despair of loss (death) and the joy of All Saints Day (and All Souls Day, on November 2). The fact that today is an ’eve (and not the day itself) suggests a sort of lack of completion. We go out begging (trick or treating), perhaps because we lack something we want. All Hallows Evening is a darker anticipation of something miraculous, the feast day of every saint that ever was. There is, nay, there must be some sort of hope at the end of despair.

Jonathan: I’ll close simply by noting a small handful of Horror books I still plan to read, since I still feel inadequately-read in the genre. The Monk, The Castle of Otranto, and Melmoth the Wanderer are all at the top of my list as Gothic subgenre works; despite my recent bad experience with Nathaniel Hawthorne’s attempt at Gothic fiction, I still want to give it a try. I might also crack open some children’s horror with Neil Gaiman’s Coraline and The Graveyard Book. Joe Hill’s Horns is on the list, but a little further down.

What say you, Rico?

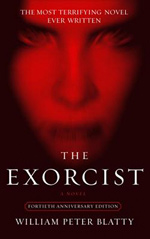

Rico: I’m likely to be more behind in my reading than you. It seems that much of the horror tradition is American, and may have roots not just in the English Gothic Novel, but also in the constant low-grade terror of North America’s indigenous population. Jung believed that tales of demonic possession waned in the American mind as rationalism took hold, and was replaced by stories of Indian abductions (and that those stories, in the 20th century turned into alien abductions!). This gets back to your idea of the unknown, and it makes me want to read all three kinds of "abduction" stories. The stories of Captain John Smith may sound more like a good old adventure story than horror, but it was a source of much anxiety to its readers in early America, who were more than familiar with the gruesome legacy of Roanoke. I also have an interest in the more recent accounts of body snatching: One such story is The Exorcist, which William Peter Blatty did not intend to be a horror novel at all. Another is I Am Legend, by Richard Matheson, which has inspired how many movies? If Jung were writing today, he might say that zombies are the latest incarnation of the abduction myth, and boy is it having its heyday, today.

Rico: I’m likely to be more behind in my reading than you. It seems that much of the horror tradition is American, and may have roots not just in the English Gothic Novel, but also in the constant low-grade terror of North America’s indigenous population. Jung believed that tales of demonic possession waned in the American mind as rationalism took hold, and was replaced by stories of Indian abductions (and that those stories, in the 20th century turned into alien abductions!). This gets back to your idea of the unknown, and it makes me want to read all three kinds of "abduction" stories. The stories of Captain John Smith may sound more like a good old adventure story than horror, but it was a source of much anxiety to its readers in early America, who were more than familiar with the gruesome legacy of Roanoke. I also have an interest in the more recent accounts of body snatching: One such story is The Exorcist, which William Peter Blatty did not intend to be a horror novel at all. Another is I Am Legend, by Richard Matheson, which has inspired how many movies? If Jung were writing today, he might say that zombies are the latest incarnation of the abduction myth, and boy is it having its heyday, today.

So that wraps up our Worlds Without End Month of Horrors! We hope you’ve all enjoyed our exploration of the Horror genre during the month of October. Cheery chills, and safe trick-or-treating!

Month of Horrors: The Shadow Over Innsmouth

This is the first installment of our October series featuring Horror novels and stories. Rico and I will be blogging about some of our favorite scary books until the end of the month, even as we laboriously add new Horror-genre titles to the database. On Halloween, we intend to offer some general thoughts on the Horror genre, and why it’s an important addition to the WWEnd site.

H.P. Lovecraft is a devisive but unambiguously influencial figure in the development of the Horror genre as we know it today. Writing what at the time was called “weird fiction,” Lovecraft drowned the genre in a sea of purple, a sea that had strange and tentacled monsters living in its depths. His stories have maintained an influence far out of proportion to his actual skill as a writer, as even his staunchest fans will admit. Something of an anachronism even in his own time (1890-1937), for the modern reader he exudes an air smelling of the worst of a disintegrated aristocracy, while ironically eschewing all aristocratic literary standards in favor of the quality of prose one would most likely find on a fan fiction message board. And yet… and yet, his vision of a universe gone mad, of gods even more malevolent than Kali or Typhoeus, of terrors lurking in the ocean’s depths, have made an impression entirely out of proportion to the man’s literary skill.

H.P. Lovecraft is a devisive but unambiguously influencial figure in the development of the Horror genre as we know it today. Writing what at the time was called “weird fiction,” Lovecraft drowned the genre in a sea of purple, a sea that had strange and tentacled monsters living in its depths. His stories have maintained an influence far out of proportion to his actual skill as a writer, as even his staunchest fans will admit. Something of an anachronism even in his own time (1890-1937), for the modern reader he exudes an air smelling of the worst of a disintegrated aristocracy, while ironically eschewing all aristocratic literary standards in favor of the quality of prose one would most likely find on a fan fiction message board. And yet… and yet, his vision of a universe gone mad, of gods even more malevolent than Kali or Typhoeus, of terrors lurking in the ocean’s depths, have made an impression entirely out of proportion to the man’s literary skill.

One of his most famous stories—and one of my personal favorites—is The Shadow Over Innsmouth, a novella that can be found in many volumes of his collected works (including The Lurking Fear and The Dunwich Horror and Others). Innsmouth serves almost as a Lovecraftian monomyth, containing his most popular tropes and plot elements in one place. Here we see the story of an ordinary man pulled gradually into an increasingly strange and terrifying revelation. Here we see the touch of madness that comes from a vision of something that ought not to be. Here we see even a hint of the Cthulu mythos that has spawned a school of imitators as numerous as the fish of the deep.

One of his most famous stories—and one of my personal favorites—is The Shadow Over Innsmouth, a novella that can be found in many volumes of his collected works (including The Lurking Fear and The Dunwich Horror and Others). Innsmouth serves almost as a Lovecraftian monomyth, containing his most popular tropes and plot elements in one place. Here we see the story of an ordinary man pulled gradually into an increasingly strange and terrifying revelation. Here we see the touch of madness that comes from a vision of something that ought not to be. Here we see even a hint of the Cthulu mythos that has spawned a school of imitators as numerous as the fish of the deep.

The narrator comes across Innsmouth almost by chance as a young man during his “coming of age” tour of New England. He is both repelled and attracted by the odd stories he hears about the town, stories of pagan cults, pirate jewels, human deformity, and an unusual abundance of fish. He decides to take the bus to Innsmouth only for a day to sate his curiosity, for he has been warned against staying the night. But, as these things often go, when he is set to leave in the evening he is told that the bus has had mechanical problems and won’t be ready for driving until the morning. Left without a choice, he does what he must to survive through the night.

I’ll end with a brief sample of Lovecraft’s prose, also from Innsmouth. His language is colorful, but tends towards the higher end of the spectrum.

I’ll end with a brief sample of Lovecraft’s prose, also from Innsmouth. His language is colorful, but tends towards the higher end of the spectrum.

It was the end, for whatever remains to me of life on the surface of this earth, of every vestige of mental peace and confidence in the integrity of Nature and of the human mind. Nothing that I could have imagined—nothing, even, that I could have gathered had I credited old Zadok’s crazy tale in the most literal way—would be in any way comparable to the daemoniac, blasphemous reality that I saw—or believe I saw. I have tried to hint what it was in order to postpone the horror of writing it down baldly. Can it be possible that this planet has actually spawned such things; that human eyes have truly seen, as objective flesh, what man has hitherto known only in febrile phantasy and tenuous legend?

Until next time, Iä-R’lyeh! Cthulhu fhtagn!

The New York Review of Science Fiction Reading Series: Lovecraft Unbound

It was a cold, rainy Manhattan evening… the shadows oozing from the alleys seemed particularly menacing. Was that a puddle of street water at the curb, or a puddle of blood? As I paced nervously through the uninviting streets, past shuttered shops and grim Brownstones, I couldn’t help but wonder who would be out on a night like this? I soon got my answer… the followers of H.P. Lovecraft! I and his other adherents were happy to brave the dreary streets to attend the latest New York Review of Science Fiction Reading Series event: the launch of the new Ellen Datlow compendium, "Lovecraft Unbound."

The reading and "soft launch" of the book took place in the SoHo Gallery of Digital Art, a bright and thoroughly hospitable space for an event like this. "Lovecraft Unbound" is the latest anthology from Ms. Datlow, a matriarch of the Horror, Science Fiction and Fantasy genres. The book is a collection of Lovecraft-inspired short stories as envisaged by some of the most formidable writers still alive and twitching. Producer and Executive Curator Jim Freund ran the evening, and he did a great job introducing the guests and hosting the reading in general.

The reading and "soft launch" of the book took place in the SoHo Gallery of Digital Art, a bright and thoroughly hospitable space for an event like this. "Lovecraft Unbound" is the latest anthology from Ms. Datlow, a matriarch of the Horror, Science Fiction and Fantasy genres. The book is a collection of Lovecraft-inspired short stories as envisaged by some of the most formidable writers still alive and twitching. Producer and Executive Curator Jim Freund ran the evening, and he did a great job introducing the guests and hosting the reading in general.

Ms. Datlow (multiple winner of the Hugo Award, the Bram Stoker Award, the World Fantasy Award, the International Guild Award, the Shirley Jackson Award, and the Locus Award, among others) began the evening explaining that she wanted to present a vision of Lovecraft "…without the tentacles, but hopefully with the flavor, the paranoia, of Lovecraft. Okay, well, some tentacles." The anthology readers on hand were, in alphabetical order, Elizabeth Bear, Richard Bowes, and Michael Cisco.

Mr. Bowes (winner of the World Fantasy Award, the Lamda Literary Award and 2006 Nebula nominee for From the Files of the Time Rangers among others) read first, from his story "The Office of Doom," a wry, thoroughly enjoyable tale. Michael Cisco (winner of the International Horror Guild Award) read his story next, "Machines of Concrete Light and Dark." It was very different in flavor but no less entertaining… a dark, bloody story that left the crowd shivering. Was it mere coincidence that none of our pictures of Mr. Cisco came out? We leave you to decide….

Ms. Bear (winner of the Hugo Award, the Locus Award for Best First Novel, the John W. Campbell Award and 2006 PKD/2007 Locus nominee for Carnival) read a portion of her story, co-written with Sarah Monette, "Mongoose." It was a rich combination of science fiction artifice and Lovecraftian dread, and definitely left the audience wanting more. (We were able to catch up to Ms. Bear after the reading, and ask her, on behalf of WWEnd readers, what she was working on next. "I’ve just handed in the draft of the second Jacob’s Ladder novel, and I’m working on a couple fantasy novels after that.")

The SoHo neighborhood was a fine choice for the book launch: it still evoked, especially at night, the gritty gloom of the previous century’s tightly packed tenements. H.P. Lovecraft (1890-1937) lived not too far away for a time, across the river in Brooklyn. That borough inspired one of his stories, "The Horror of Red Hook", written in 1925.

"Lovecraft Unbound" successfully evokes that brand of grisly horror and macabre fantasy that Lovecraft spawned a century ago. The stories are as rewarding and collectively gratifying as you would hope and expect from an Ellen Datlow anthology, and we’re happy to recommend it to WWEnd readers. And for those in the greater New York area, we also recommend the NYRSF Reading Series! They do after all have access to some of the best talent in the business, and their readings are a monthly event worth checking out.

Full Details

Full Details